By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

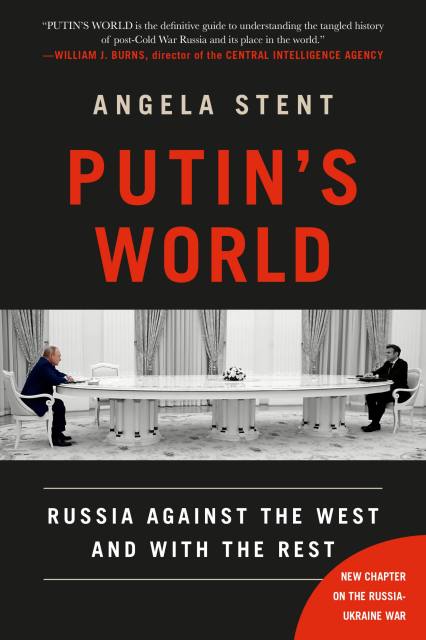

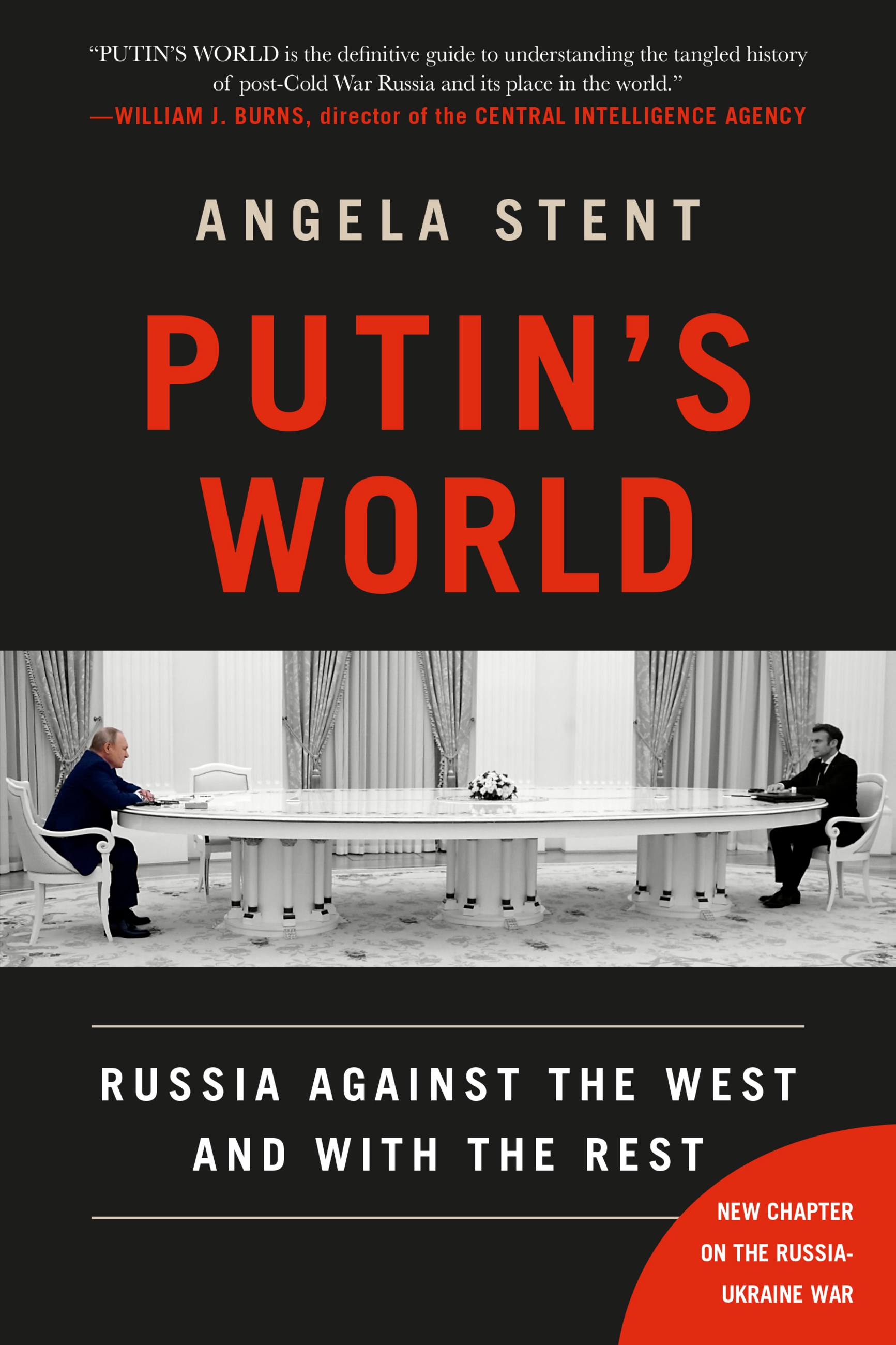

Putin’s World

Russia Against the West and with the Rest

Contributors

By Angela Stent

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 26, 2019

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781455533015

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $42.00 $53.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 26, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this revised version that includes an exclusive new chapter on the Russia-Ukraine war, renowned foreign policy expert Angela Stent examines how Putin created a paranoid and polarized world—and increased Russia's status on the global stage.

How did Russia manage to emerge resurgent on the world stage and play a weak hand so effectively? Is it because Putin is a brilliant strategist? Or has Russia stepped into a vacuum created by the West's distraction with its own domestic problems and US ambivalence about whether it still wants to act as a superpower? Putin's World examines the country's turbulent past, how it has influenced Putin, the Russians' understanding of their position on the global stage and their future ambitions—and their conviction that the West has tried to deny them a seat at the table of great powers since the USSR collapsed.

This book looks at Russia's key relationships—its downward spiral with the United States, Europe, and NATO; its ties to China, Japan, the Middle East; and with its neighbors, particularly the fraught relationship with Ukraine. Putin's World will help Americans understand how and why the post-Cold War era has given way to a new, more dangerous world, one in which Russia poses a challenge to the United States in every corner of the globe—and one in which Russia has become a toxic and divisive subject in US politics.

How did Russia manage to emerge resurgent on the world stage and play a weak hand so effectively? Is it because Putin is a brilliant strategist? Or has Russia stepped into a vacuum created by the West's distraction with its own domestic problems and US ambivalence about whether it still wants to act as a superpower? Putin's World examines the country's turbulent past, how it has influenced Putin, the Russians' understanding of their position on the global stage and their future ambitions—and their conviction that the West has tried to deny them a seat at the table of great powers since the USSR collapsed.

This book looks at Russia's key relationships—its downward spiral with the United States, Europe, and NATO; its ties to China, Japan, the Middle East; and with its neighbors, particularly the fraught relationship with Ukraine. Putin's World will help Americans understand how and why the post-Cold War era has given way to a new, more dangerous world, one in which Russia poses a challenge to the United States in every corner of the globe—and one in which Russia has become a toxic and divisive subject in US politics.

-

"Informed by its author's distinguished career in government and academia, this account of Russian President Vladimir Putin's worldview provides an important window into one of the key geopolitical challenges of our time. Casual observers and seasoned experts will benefit from Dr. Stent's brilliant exploration of Putin's strategy and its disturbing implications for the West."Former Secretary of State Madeleine K. Albright

-

"Like the judo player he once was, Vladimir Putin has figured out ways to assert Russian power despite his nation's weakness. Understanding how he does it is crucial to America, and Angela Stent's deeply knowledgeable and readable book provides brilliant insights."Walter Isaacson, New York Times bestselling author of Leonardo Da Vinci and Einstein

-

"PUTIN'S WORLD offers a timely 21st century update on George Kennan's Long Telegram. Russians understand their country through history, geography, empire-and stories of 'great men.' Angela Stent deftly explains how Putin's version of Russian exceptionalism has been redrawing maps of power in Eurasia and beyond. In an era of strongmen who are seeking a new concert of power, Stent offers the wise perspective that we should consider Russia as it is, not as we might wish it to be."Robert B. Zoellick, former president of the World Bank, US Trade Representative, and US Deputy Secretary of State

-

"From one of the leading experts on Russian foreign policy, PUTIN'S WORLD is a highly engaging, comprehensive overview of Moscow's international relations. Angela Stent deftly explains Russia's complex role at a fraught moment in history, drawing deeply on the country's history, culture, and other key factors determining Russians' conceptions of themselves and the world."Gregory Feifer, author of Russians: The People Behind the Power

-

"PUTIN'S WORLD is the definitive guide to understanding the tangled history of post-Cold War Russia and its place in the world. Angela Stent offers a thoughtful, sober, and elegantly-written perspective that could not be more timely."US Ambassador William J. Burns

-

"[Stent] counsels strategic patience and preparedness -- and suggests that it would be wise to expect the unexpected."Foreign Affairs

-

"Stent expertly walks readers through Moscow's relations with every region in the world, avoiding the hysteria that warps discussion of the country. Aware that too many books about Russian foreign policy arrive instantly obsolete because they lack a foundation in history or political culture, Stent opens with those subjects...and the book culminates in a clear-eyed portrayal of the inescapably troubled U.S.-Russia relationship."Washington Post

-

"An incisive exploration of 'how and why Russia has returned to the world stage'...[Stent] offers a deeply informed look at why Russia, directed by President Vladimir Putin, persists in behaving in what the West regards as an exceedingly maddening, paranoid, and often aggressive manner...A compelling historico-psychological work delineating how the West should respond to Russia going forward."Kirkus (Starred Review)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use