Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

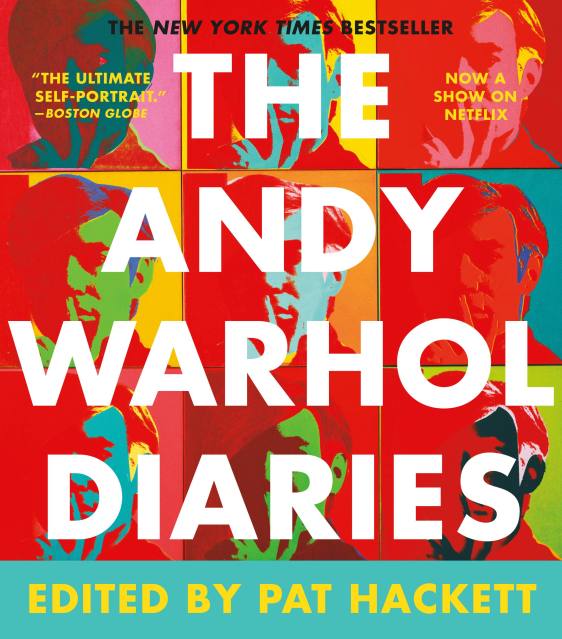

The Andy Warhol Diaries

Contributors

By Andy Warhol

By Pat Hackett

Formats and Prices

Price

$16.99Price

$20.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $30.00 $38.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 29, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This international literary sensation turns the spotlight on one of the most influential and controversial figures in American culture. Filled with shocking observations about the lives, loves, and careers of the rich, famous, and fabulous, Warhol's journal is endlessly fun and fascinating.

Spanning the mid-1970s until just a few days before his death in 1987, THE ANDY WARHOL DIARIES is a compendium of the more than twenty thousand pages of the artist's diary that he dictated daily to Pat Hackett. In it, Warhol gives us the ultimate backstage pass to practically everything that went on in the world-both high and low. He hangs out with "everybody": Jackie O ("thinks she's so grand she doesn't even owe it to the public to have another great marriage to somebody big"), Yoko Ono ("We dialed F-U-C-K-Y-O-U and L-O-V-E-Y-O-U to see what happened, we had so much fun"), and "Princess Marina of, I guess, Greece," along with art-world rock stars Jean-Michel Basquiat, Francis Bacon, Salvador Dali, and Keith Haring.

Warhol had something to say about everyone who crossed his path, whether it was Lou Reed or Liberace, Patti Smith or Diana Ross, Frank Sinatra or Michael Jackson. A true cultural artifact, THE ANDY WARHOL DIARIES amounts to a portrait of an artist-and an era-unlike any other.

Genre:

-

"The ultimate self-portrait."Boston Globe

-

"A remarkable literary achievement."New York Magazine

-

"No study of Manhattan society in the strobe-lit 1970s or in the shadow of AIDS will be possible without consideration of THE ANDY WARHOL DIARIES, which provides an unforgettable portrait of what a set of people imagined themselves to be and of what they really were."Baltimore Sun

-

"Warhol on Warhol, as dictated by Warhol...noble in its obsessiveness."New York Times

-

"This extraordinarily revealing diary paints a more penetrating portrait of our time's Glitterati Era than any of Andy's fable canvases."Forbes

-

"Warhol's observations about the stream of people around him are rarely less than brilliant."Details

-

"A vivid picture of this enigmatic man...It abounds with celebrity gossip...It provides the definitive answer to the oft-asked question, 'What was Andy Warhol really like?'"Philadelphia Inquirer

-

"Cruel, sexy, and sometimes heartbreaking...Like classic literary diarist—Pepys, Byron—Warhol is no neutral observer, but a character in his own right...People may pick up THE ANDY WARHOL DIARIES to see celebrities with (literary) pants down and spoons up there noses...But they'll remember the strange creature who watched it all happen."Newsweek

-

"Fascinating...disturbing...decadent...no one emerges unscathed. Warhol managed to crystallize the times in which he lived better than just about anyone."Variety

-

"The diaries go far beyond idle gossip. They are a re-creation of a time and a place in America...Endless fascinating...the Warhol diaries will stand for at least a century, if not more."Detroit News

-

"Warhol's diaries will provide laughs, gasps and thrill for those he mentions, for those who want a quick peek through their shades."New York Daily News

-

"The author sooner or later catches everyone he knows with their pants down...The tone is pure Warhol. At once insightful and distracted...A book that revels in nakedness."Chicago Tribune

-

"A remarkable tour of Warhol's unusual frame of mind, the circles of slick celebrities he moved in, the friends he made, the enemies he made, the enemies he had, and the years he could not shake...The material seems so scandalous it's a wonder it made print."Bergen Record

-

"Gossip lovers will revel in the roster of names parading through Warhol's life—Elizabeth Taylor, Jack Nicholson, and Mick Jagger only head the list—while others will find clues to Warhol the person in his descriptions and comments...The book does much to shed light on the character of a man who hid from an intrusive public while living in the blinding glare of a perpetual spotlight."Houston Post

-

"Will have many going great, wow, and even golly."Vanity Fair

-

"Great social history...an anecdote a minute."Village Voice

- On Sale

- Nov 29, 2009

- Page Count

- 864 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446571241

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use