By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

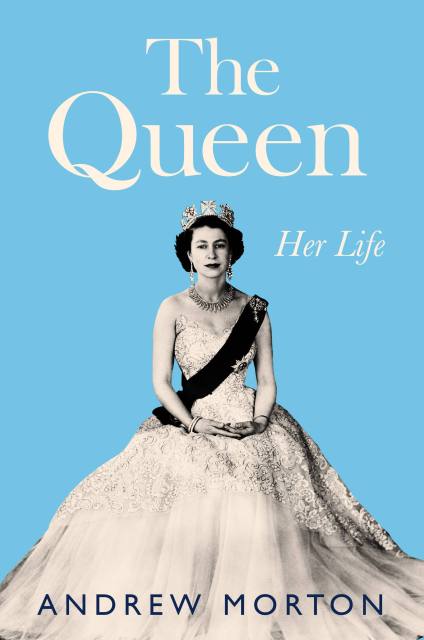

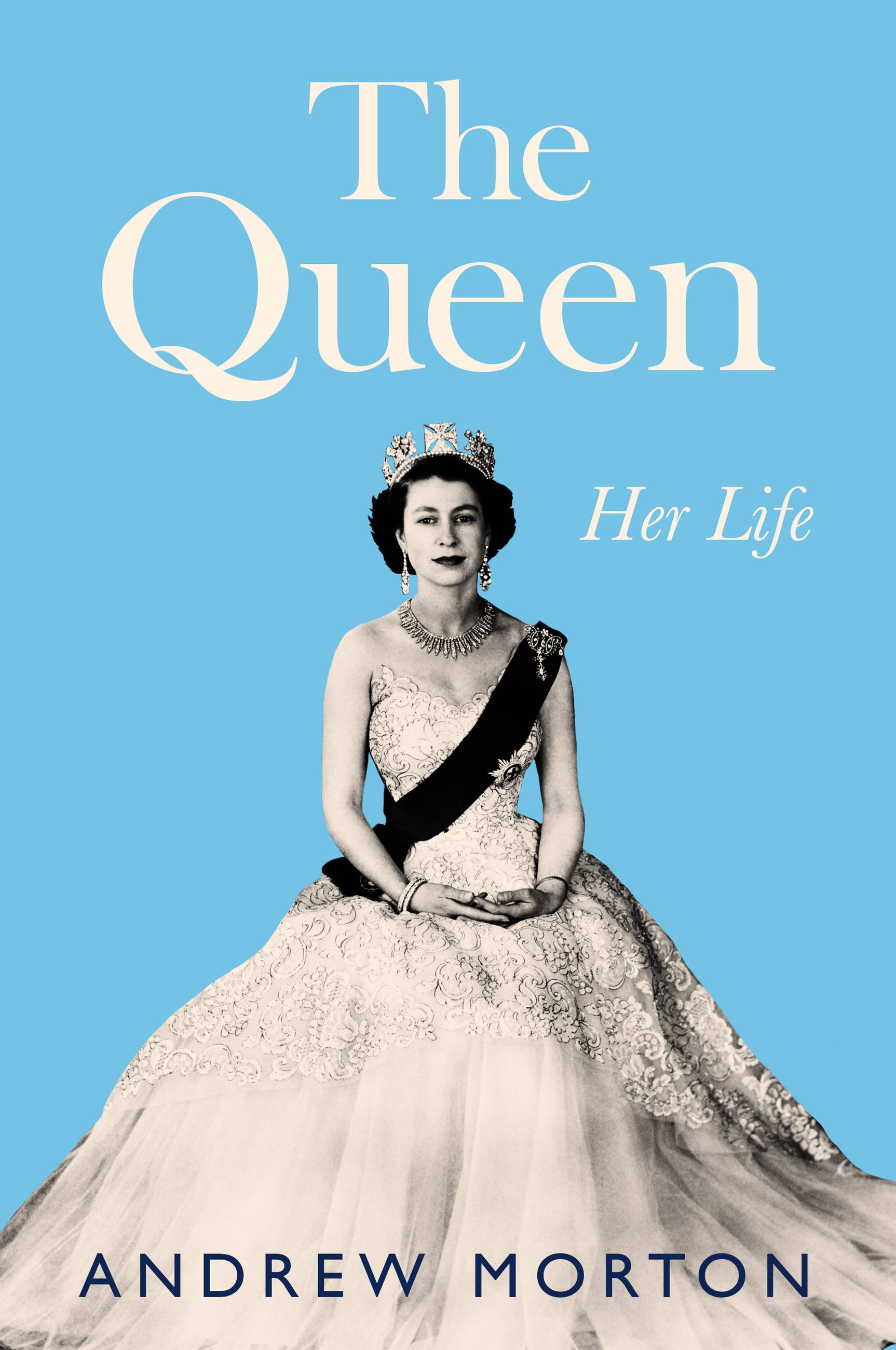

The Queen

Her Life

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 15, 2022

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538700440

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $31.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 15, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Painfully shy, Elizabeth Windsor’s personality was well suited to her youthful ambition of living quietly in the country, raising a family, and caring for her dogs and horses. But when her uncle, King Edward VIII, abdicated, she became heir to the throne—embarking on a journey that would test her as a woman and queen.

Ascending to the throne at only 25, this self-effacing monarch navigated endless setbacks, family conflict, and occasional triumphs throughout her 70 years as the Queen of England. As her mettle was tested, she endeavored to keep the monarchy relevant culturally, socially, and politically, often in the face of resistance from inside the institution itself. And yet the greatest challenges she faced were often inside her own family, forever under intense scrutiny; from rumors about her husband’s infidelity, her sister’s marital breakdown, Princess Diana’s tragic death, to the recent departure of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle.

Now in The Queen, renowned biographer Andrew Morton takes an in-depth look at Britain’s longest reigning monarch, exploring the influence Queen Elizabeth had on both Britain and the rest of the world for much of the last century. From leading a nation struggling to restore itself after the devastation of the second World War to navigating the divisive political landscape of the present day, Queen Elizabeth was a reluctant but resolute queen. This is the story of a woman of unflagging self-discipline who will long be remembered as mother and grandmother to Great Britain, and one of the greatest sovereigns of the modern era.

-

“Andrew Morton has been the best known and most accessible, if not the foremost, biographer of England’s royal family.”New York Times

-

“A narrative that hits all the plot points… of course, this is precisely as Queen Elizabeth would have wanted it.”Washington Post

-

"A fitting tribute to a long reign."Kirkus

-

“Incisive character sketches and a touch of gossip make this admiring biography go down smooth.”Publishers Weekly

-

"Morton packs a great deal of interesting material between the covers . . . interesting and energetically written . . . [T]here is much to commend in this effort at capturing a unique woman who will remain an enigma for some time to come."BookReporter.com

-

"Morton uses archival research and his relationships with palace insiders to paint a complete written portrait of Britain’s longest reigning monarch . . . Morton also unpacks some buzzier tidbits including rumors about her husband’s infidelity, her sister’s tumultuous marriage, Princess Diana’s death, and Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s high profile exit from the royal fam."The Skimm

-

"This is something historians will enjoy and the most avid Anglophile should pounce on . . . will make you smile; enjoyment like you’ll get here is hard to hide."Naples Daily News

-

“It's hard to come away from this book without feeling some affection for [the queen]—regardless of your views on the monarchy.”Star Tribune

-

Praise for Elizabeth & Margaret:New York Times

"The king of royal tea...Morton provides rich context on the coldness of royal life...Margaret’s tale is revelatory." -

"A diligent and well-researched job, examining the closeness of the sisters and their conflicted relationship in a seamless, readable way."Wall Street Journal

-

“Deliciously detailed, sometimes gossipy, often moving, this in-depth examination of royal siblings is sure to be in demand.”Booklist

-

“Morton’s insightful analysis of the complex relationship between Queen Elizabeth and Princess Margaret succeeds in humanizing two extremely public figures and the myths surrounding them. It will engage history buffs, biography readers, and especially fans of The Crown.”Library Journal

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use