By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

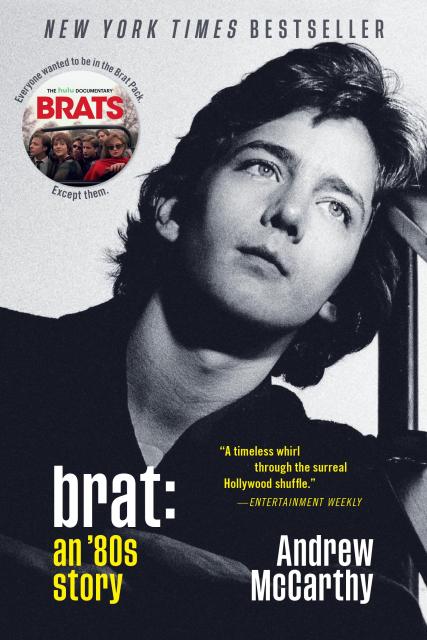

Brat

An '80s Story

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 10, 2022

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538754290

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 10, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Everyone knows Andrew McCarthy from his iconic movie roles in Pretty in Pink, St. Elmo’s Fire, Weekend at Bernie’s, and Less than Zero. Part of the legendary Brat Pack (including Rob Lowe, Molly Ringwald, Emilio Estevez, and Demi Moore), his filmography has come to represent both a genre of film and an era of pop culture.

In Brat, McCarthy focuses on that singular moment in time. The result is a revealing look at coming of age in a maelstrom, reckoning with conflicted ambition, innocence, addiction, and masculinity. 1980s New York City is brought to vivid life in these pages, from scoring loose joints in Washington Square Park to skipping school in favor of the dark revival houses of the Village—where he fell in love with the movies that would change his life.

Filled with personal revelations of innocence lost to heady days in Hollywood with John Hughes and an iconic cast of characters, Brat is a surprising and intimate story of an outsider caught up in a most unwitting success.

-

“With wit, wisdom, and a depth of honesty that will resonate to your core, Andrew McCarthy lays down the armor of an unknowable scared boy to shine light on the complex and conflicting pieces that make up the intelligent, introspective, compassionate, and wise man who is even more lovable than the boy we first fell in love with.”Demi Moore, actress and New York Times bestselling author of Inside Out

-

“How lucky we are that Andrew McCarthy, such a key player in the Brat Pack phenomenon, should happen to be so naturally gifted a writer and so piercingly, ruefully, and hilariously wise, intelligent, and insightful a chronicler of that wild ride. He somehow survived the madness, and the result is a truly rewarding addition to the bookshelves of film lovers everywhere.”Stephen Fry, writer, actor, and comedian

-

“Andrew McCarthy is one of the best. He’s a dogged character: witty and wry, self-abnegating, always questioning his success. Thanks to his prodigious talents, he succeeds beautifully. This unlikely leading man explores masculinity, success, the dangers of fame, ambition, and cigarettes in this elegant and humorous coming-of-age story of a Brat Pack actor turned director and writer.”Candace Bushnell, bestselling author and creator of Sex and the City

-

“My only quibble with this absorbing, thoughtful, and sometimes painfully honest memoir is with the title; McCarthy is anything but a brat. He is certainly an unlikely movie star, and the story of how this diffident and insecure young man found himself at the center of the culture in the 1980s—and then decided to walk away from it all—makes for a fascinating read.”Jay McInerney, author of Bright Lights, Big City and The Good Life

-

"With “Brat: An ’80s Story,” out May 11, [McCarthy] offers not only a recollection of his experiences shooting films like “Pretty in Pink,” “Mannequin,” “Weekend at Bernie’s” and the Georgetown-set ensemble “St. Elmo’s Fire,” but a broader exploration of the tangled nature of success, fame, his complicated relationship with his father and his personal demons. Less sordid tell-all, more contemplative reflection."The Washington Post

-

"[McCarthy] reveals a few fun behind-the-scenes details (he had to reshoot the prom scene in Pretty in Pink while wearing an ill-fitting wig!), but [Brat] is no salacious tell-all. With bracing intimacy and honesty, he digs deep to chronicle his own self-destructive alcohol abuse and his intense discomfort in the spotlight."Parade

-

"[McCarthy's] perspective is welcome, his insight more, much more, than zero."USA Today

-

"McCarthy’s stories not only offer dishy name-dropping, but also near-constant humorous self-deprecation as he looks at his past with the advantages of age and time."A.V. Club

-

“Shrewd storytelling ...brutal honesty…a timeless whirl through the surreal Hollywood shuffle."Entertainment Weekly

-

“[E]lectrifying. . . [C]ompelling and lyrical.”Irish Independent

-

"If “Pretty in Pink,” “St. Elmo’s Fire” and “Less than Zero” continue to stay in heavy rotation on your must-watch list, odds are Andrew McCarthy’s new memoir is as much a no-brainer as Andie ending up with Blane at the prom. The Brat Packer focuses on growing up in New York City in the ’80s, getting candid about lost innocence and the highs and lows of his rise to fame in Hollywood."CNN

-

“Students of acting will appreciate learning about McCarthy’s versions of method acting and his struggles with performing for a camera. Fans of ’80s cinema will love the chance to reminisce.”Library Journal

-

“[A] heartful memoir…McCarthy is clear-eyed and unsparing about Hollywood but takes the emotional intensity of the actor’s craft and life seriously. The result is a riveting portrait of the artist as a young man.”Publishers Weekly

-

"[L]ong-awaited. . . [A]n incessantly grabby page-turner."National Review

-

"[Brat] is an honest exploration of the highs and lows of being part of the Hollywood crowd."Town & Country

-

"Aside from a squeal-inducing trip down memory lane for anyone who grew up in the Brat Pack era, Andrew McCarthy's Brat: An '80s Story is a surprisingly, and refreshingly, honest memoir."Forbes

-

"Andrew McCarthy is giving readers an inside look at what life as a member of Hollywood's Brat Pack was really like in Brat: An '80s Story. His memoir focuses on what it was like for the Pretty in Pink star to come of age during one of the most significant eras in Hollywood's pop culture history."PopSugar

-

"Andrew McCarthy, the star of St. Elmo’s Fire and Pretty in Pink, looks back on one glitzy, debaucherous decade in Brat. . . [T]his memoir is a must-read for any film fan."Bustle

-

"[Brat] has a little something for everyone. . . [A]n entertaining, yet self-reflective, romp down memory lane. McCarthy’s writing is solid and flowing, honest and critical. Fans with a special place in their heart for ‘80s nostalgia are sure to enjoy the stories shared here."The Nerd Daily

-

PRAISE FOR ANDREW MCCARTHY

-

"Soulful and searching . . . McCarthy's prose shines with intelligence and intimacy . . . A long, strange trip on the direction of full-throttle love."Cheryl Strayed, New York Times Book Review

-

"McCarthy ponders some of the biggest and most frightening questions surrounding intimacy: How does a loner connect? How does a traveler settle down? How do we merge into families without losing ourselves? The answer seems to be that all these things are impossible...and yet somehow we do it anyway. There is much to be learned, and much to be admired, in this elegant, thoughtful story."Elizabeth Gilbert, bestselling author of Eat, Pray, Love

-

"A candid, touching, and often humorous new memoir."San Francisco Chronicle

-

"Andrew McCarthy treks from Baltimore to the Amazon, exploring his commitment issues as fearlessly as he scales Mount Kilimanjaro."Elle

-

"Brave and moving. . . McCarthy's keen sense of scene and storytelling ignites his accounts...[t]hreaded with an exemplary vulnerability and propelled by a candid exploration of his own life's frailties."National Geographic

-

"This is not some memoir written by an actor who fancies himself a world traveler. McCarthy really is a world traveler - and a damned fine writer, too...To readers who think, "Andrew McCarthy? Really?" the answer is a resounding and emphatic yes. Really."Booklist

-

"Rarely have I seen the male psyche explored with such honesty and vulnerability. This is the story of a son, a father, a brother, a husband, a man who finds the courage not only to face himself, but to reveal himself, and, in so doing, illuminates something about what it is to be human, fully alive, and awake."Dani Shapiro, author of Devotion

-

"It's hard to write books that are both adventurous and touching, but Andrew McCarthy manages to pull it off and more! A smart, valuable book."Gary Shteyngart, bestselling author of Super Sad True Love Story and Absurdistan

-

"Where lesser writers might reach for hyperbole and Roget to describe such exotic lands as Patagonia, Kilimanjaro and Baltimore, in The Longest Way Home, McCarthy leans on subtlety, a straightforward style and hard-won insights to allow his larger stories to unfold. It's not hard to imagine him as the solitary figure in the café, scribbling in a notebook by candlelight, making the lonely, tedious work of travel writing look romantic and easy."Chuck Thompson, author of Better Off Without 'Em and Smile When You're Lying

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use