Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

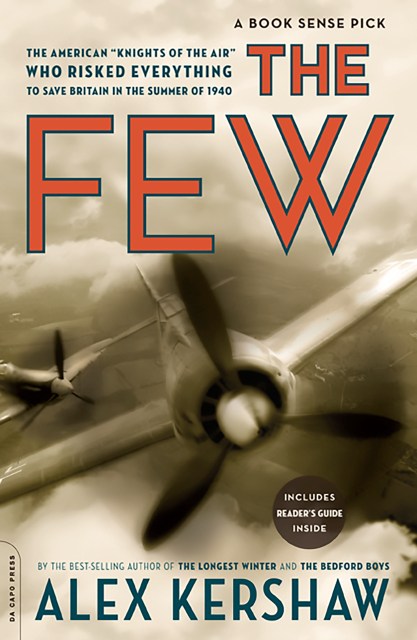

The Few

The American "Knights of the Air" Who Risked Everything to Fight in the Battle of Britain

Contributors

By Alex Kershaw

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 28, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From the author of national bestsellers The Bedford Boys and The Longest Winter comes “a rousing tale of little-known heroes” (Booklist).

The Few tells the dramatic and unforgettable story of eight young Americans who joined Britain’s Royal Air Force, defying their country’s neutrality laws and risking their U.S. citizenship to fight side-by-side with England’s finest pilots in the summer of 1940-over a year before America entered the war. Flying the lethal and elegant Spitfire, they became “knights of the air” and with minimal training but plenty of guts, they dueled the skilled and fearsome pilots of Germany’s Luftwaffe. By October 1940, they had helped England win the greatest air battle in the history of aviation. Winston Churchill once said of all those who fought in the Battle of Britain, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” These daring Americans were the few among the “few.” Now, with the narrative drive and human drama that made The Bedford Boys and The Longest Winter national bestsellers, Alex Kershaw tells their story for the first time.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 28, 2007

- Page Count

- 360 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306815720

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use