Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

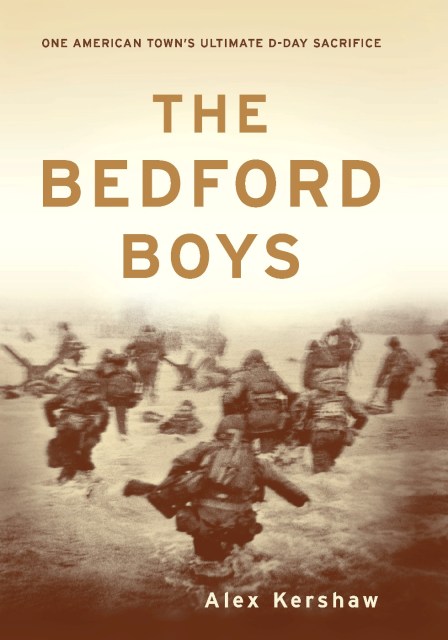

The Bedford Boys

One American Town's Ultimate D-day Sacrifice

Contributors

By Alex Kershaw

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $14.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 18, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

June 6, 1944: Nineteen boys from Bedford, Virginia — population just 3,000 in 1944 — died in the first bloody minutes of D-Day.

They were part of Company A of the 116th Regiment of the 29th Division, and the first wave of American soldiers to hit the beaches in Normandy. Later in the campaign, three more boys from this small Virginia town died of gunshot wounds. Twenty-two sons of Bedford lost–it is a story one cannot easily forget and one that the families of Bedford will never forget.

The Bedford Boys is the true and intimate story of these men and the friends and families they left behind. Based on extensive interviews with survivors and relatives, as well as diaries and letters, Kershaw’s book focuses on several remarkable individuals and families to tell one of the most poignant stories of World War II–the story of one small American town that went to war and died on Omaha Beach.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 18, 2008

- Page Count

- 328 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306817786

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use