Growing Up on the Margins

When I was seven years old, about a month into my second-grade year, my parents told my older brother and me that they’d bought a house on the other side of town and we were moving. I’m sure I was sad to leave the only house I’d ever lived in, my friends, and my school, which was pretty racially diverse compared to most others in town. But a part of me must have been excited—about a new bedroom to decorate, a new neighborhood to explore, and new friends to make at my new school.

When I was seven years old, about a month into my second-grade year, my parents told my older brother and me that they’d bought a house on the other side of town and we were moving. I’m sure I was sad to leave the only house I’d ever lived in, my friends, and my school, which was pretty racially diverse compared to most others in town. But a part of me must have been excited—about a new bedroom to decorate, a new neighborhood to explore, and new friends to make at my new school.

I don’t remember if my parents told me much about the racial dynamics of that school, but I will never forget walking into my new classroom for the first time and being introduced to my teacher and fellow students…because every single face was white.

Growing up in Springfield, Missouri, I was used to being part of a small community of Black people; even though our town in the Ozarks was the third-largest city in the state, the population was only about 150,000 people when I was a kid, and of that number, only 3 percent were Black. Still, before we moved, I was used to seeing at least a few Black people at my school, and in the neighborhood, and a whole congregation of Black people at our Baptist church every Sunday.

But when we moved, we settled down in what was considered the white side of town. We were the first family to integrate our street, and I was the only Black girl in my class. This would become my new normal, often being the only Black person in spaces, including my dance school, where I spent several hours a week for nearly a decade, taking tap classes. I got used to it: being stared at when we talked about slavery, Martin Luther King Jr., and Rosa Parks in class; people touching my hair to “see how it felt” without asking; friends shoving their arm next to mine after summer vacation as they declared that with their new tan, they were “almost as dark as me.”

I was lucky to be raised in a household full of Black pride, despite living in such a white community. I was gifted Black dolls when my parents could find them. Copies of Jet, Ebony, and Essence were regularly delivered to the house. My parents cooked the Southern food they’d grown up with in rural Arkansas, and devotedly supported Black artists, from musicians to authors to actors.

Throughout the years, I had a few Black friends, but most of them were from church, or friends of the family. It seemed that as soon as I made a new Black friend, they moved away to a different school or town. Not that there were that many of us; my entire time in school, I was one of only a handful of Black kids in my grade—if that—and the surrounding grades weren’t any better. Usually worse.

Like Alberta, the main character inThe Only Black Girls in Town, I had a great group of friends in seventh grade. Besides dance, I was involved in a lot of extracurricular activities in junior high, including the track team, band, and cheerleading. I didn’t dwell on the fact that I was different from everyone else, but like Alberta, I would have been unbelievably thrilled if another Black girl had moved in across the street.

Of course, as Alberta and her fathers discuss in the book, simply sharing a skin color didn’t automatically mean I was destined to get along with every Black girl I met. But I missed having someone to talk to about what it felt like to be Black in such a white town— particularly, though I didn’t know the word at the time, dealing with microaggressions. My parents were supportive but wanted me to have a thick skin; after all, they grew up in the South during the 1950s and 1960s, and though they didn’t talk much about it, I would never see anything as terrible as what they lived through.

But I wanted someone to ask about the things people said that seemed…off.Was that racist? I would wonder as someone expressed with surprise how articulate I was. Most of the time, that icky feeling that crept up the back of my neck meant that what someone had said was in fact racist, even if it wasn’t intended that way. I wanted someone to confirm that for me, though, and to tell me that those things people said to me—microaggressions—weren’t okay.

I wrote The Only Black Girls in Town because I wanted to write a story that brings Black girls on the margins into the spotlight. I wanted them to feel empowered to speak up for themselves and to speak out against bigotry and racism, even if it comes from people who play an important role in their lives.

I wanted them to know that I see them, that they are not alone, and that their stories are needed just as much as everyone else’s.

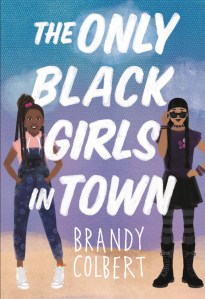

From award-winning YA author Brandy Colbert comes a debut middle-grade novel about the only two Black girls in town who discover a collection of hidden journals revealing shocking secrets of the past.

Beach-loving surfer Alberta has been the only Black girl in town for years. Alberta's best friend, Laramie, is the closest thing she has to a sister, but there are some things even Laramie can't understand. When the bed and breakfast across the street finds new owners, Alberta is ecstatic to learn the family is black—and they have a 12-year-old daughter just like her.

Alberta is positive she and the new girl, Edie, will be fast friends. But while Alberta loves being a California girl, Edie misses her native Brooklyn and finds it hard to adapt to small-town living.

When the girls discover a box of old journals in Edie's attic, they team up to figure out exactly who's behind them and why they got left behind. Soon they discover shocking and painful secrets of the past and learn that nothing is quite what it seems.