Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

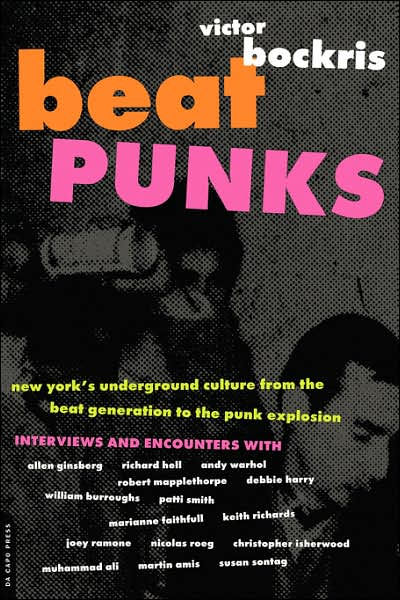

Beat Punks

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$21.99Format

Format:

Trade Paperback $21.99This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 30, 2000. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Here, accompanied by dozens of unique photographs, are the very best of Victor Bockris’s infamous interviews, essays, and observations on the stars of downtown Manhattan in the 1970s and 1980s. The internationally acclaimed biographer Bockris was there as a witness, friend, collaborator, and co-conspirator. Some of the stars were founding members of Beat or Punk, others were just passing through. But all of them—rockers, rebels, artists, and intellectuals—revealed more to Bockris than they did to any other writer: Allen Ginsberg, Richard Hell, Andy Warhol, Robert Mapplethorpe, Debbie Harry, William Burroughs, Patti Smith, Marianne Faithfull, Keith Richards, Terry Southern, Martin Amis, and Susan Sontag. Bockris’s conclusion—that Punk owed the Beats a big debt and that the Beats were in turn re-animated by the Punks—is argued from the perspective of someone who was in the thick of it, and who loved every minute of it.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Nov 30, 2000

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306809392

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use