Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

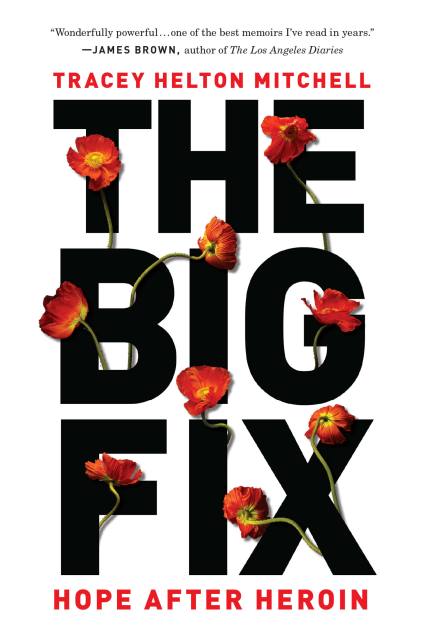

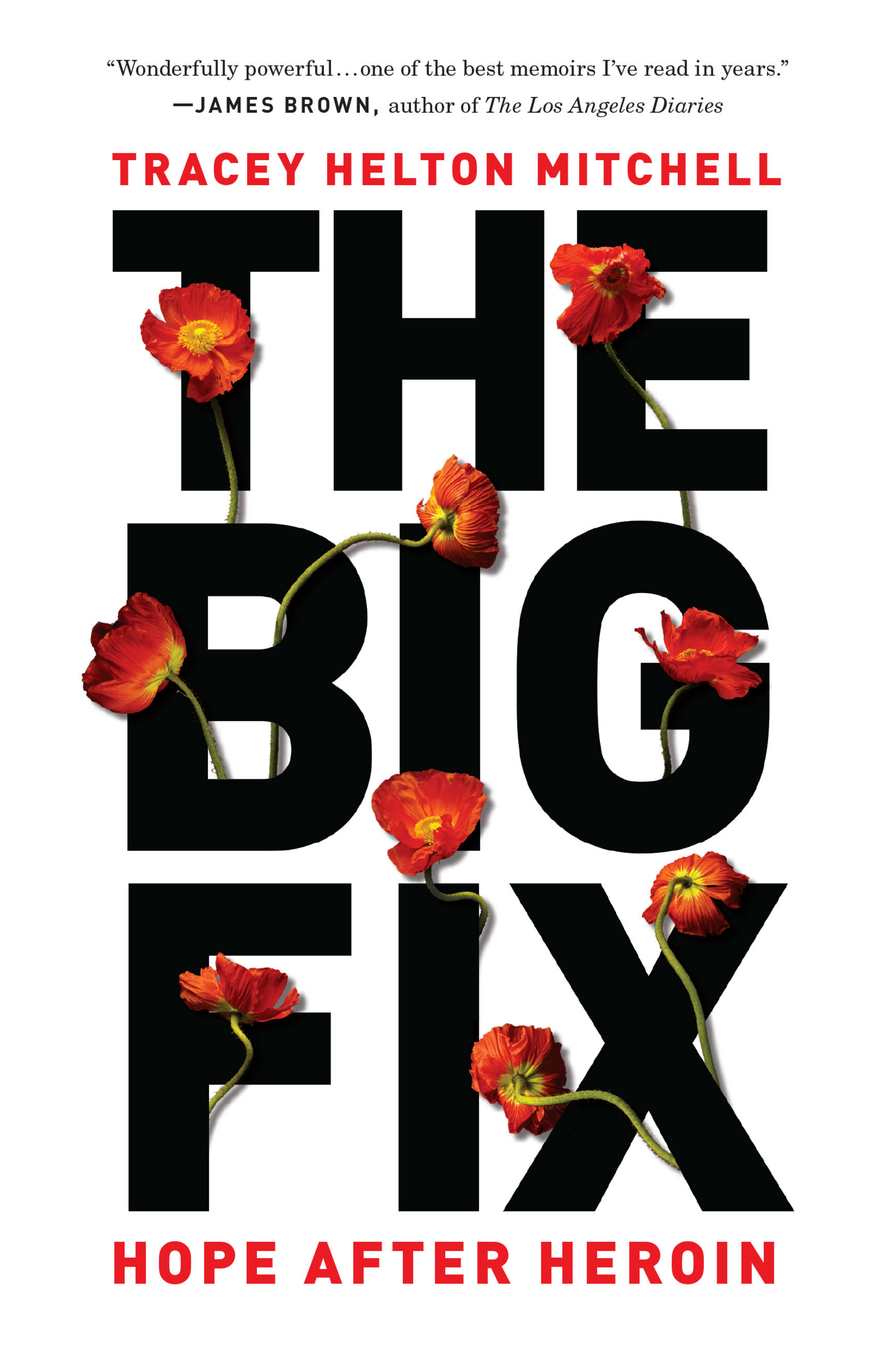

The Big Fix

Hope After Heroin

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 4, 2017

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580056632

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 4, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

After surviving nearly a decade of heroin abuse and hard living on the streets of San Francisco’s Tenderloin District, Tracey Helton Mitchell decided to get clean for good.

With raw honesty and a poignant perspective on life that only comes from starting at rock bottom, The Big Fix tells her story of transformation from homeless heroin addict to stable mother of three—and the hard work and hard lessons that got her there. Rather than dwelling on the pain of addiction, Tracey focuses on her journey of recovery and rebuilding her life, while exposing the failings of the American rehab system and laying out a path for change.

Starting with the first step in her recovery, Tracey re-learns how to interact with men, build new friendships, handle money, and rekindle her relationship with her mother, all while staying sober, sharp, and dedicated to her future. A decidedly female story of addiction, The Big Fix describes the unique challenges faced by women caught in the grip of substance abuse, such as the toxic connection between drug addition and prostitution.

Tracey’s story of hope, hard work, and rehabilitation will inspire anyone who has been affected by substance abuse while offering hope for a better future.