Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

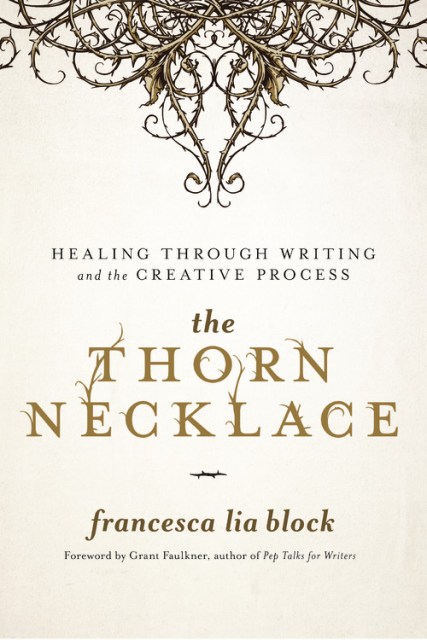

The Thorn Necklace

Healing Through Writing and the Creative Process

Contributors

Foreword by Grant Faulkner

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 1, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580057516

Price

$35.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $35.00 $46.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 1, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Francesca Lia Block is the bestselling author of more than twenty-five books, including the award-winning Weetzie Bat series. Her writing has been called “transcendent” by The New York Times, and her books have been included in “best of” lists compiled by Time magazine and NPR.

In this long-anticipated guide to the craft of writing, Block offers an intimate glimpse of an artist at work and a detailed guide to help readers channel their own experiences and creative energy. Sharing visceral insights and powerful exercises, she gently guides us down the write-to-heal path, revealing at each turn the intrinsic value of channeling our experiences onto the page.

Named for the painting by Frida Kahlo, who famously transformed her own personal suffering into art, The Thorn Necklace offers lessons on life, love, and the creative process.

-

"In the midst of untangling her own deep-seated vulnerabilities and dreams, the incandescent Francesca Lia Block shares the twelve questions that help shape her words; they will become essential for every writer in search of a light in the literary wilderness."

--Jade Chang, author of the New York Times bestseller The Wangs vs. the World

-

"Francesca Lia Block turns her unique punk-fairie style in a new direction in this fast-paced memoir of hope, disaster, magic, and sheer raw talent, mated with a down-to-earth approach to writing. This double dose of Block, as teacher and writer, is a combination sure to enchant and inform."

--Janet Fitch, bestselling author of White Oleander and The Revolution of Marina M.

-

"The best art begins with the worst pain. In The Thorn Necklace, Francesca Lia Block shepherds us through the process that transforms wounds into words. The transformation's an alchemical one. The prima materia of daily living becomes the base metal of the soul's gold. By turns personal, masterfully intimate, and practical, this book is a must for any writer who aims to get at the heart of all matters: the heart.

--Jill Alexander Essbaum, author of the New York Times bestseller Hausfrau

-

"A moving memoir and a wildly helpful guide to fiction writing. Francesca Lia Block demystifies the creative process in a way that makes the world feel magical."

--Chris Baty, author of No Plot? No Problem! and Ready, Set, Novel and founder of National Novel Writing Month

-

"Francesca's work stares unblinkingly into the face of human complexity, of suffering as well as love and joy. She's a master (mistress?) of the craft."

--Samantha Dunn Camp, author of Failing Paris -

"Francesca Lia Block helped to set the foundation for what the magical (or shall I say magickal?) realism genre is today."

--The San Francisco Examiner -

"Francesca Lia Block writes about the real Los Angeles better than anyone since Raymond Chandler."

--The New York Times -

"[Block] is the sorceress of iridescent language."

--Kirkus Reviews -

"In this lyrical and haunting meditation on the craft of writing, Block...cracks open her psyche and lays it bare in the hopes of inspiring other storytellers-to-be. Wise and inspiring, this is a must-read for artists of all stripes."Booklist **starred review**

-

"The Thorn Necklace is a 'grimoire,' a meditation on turning agony into art, at the same time that it functions as a guide to being creative. Block viscerally shows how she has taken the setbacks of her own life ...and transformed them into literature that has ultimately inspired and sustained her readers....Mesmerizing."Los Angeles Review of Books

-

"Weaves memoir with lessons on the craft of writing to create a unique and visceral guide to creativity"Bitch

-

"Block blends examples from her own life with analyses of famous works of literature to help writers deliver a successful story."Writer magazine