By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

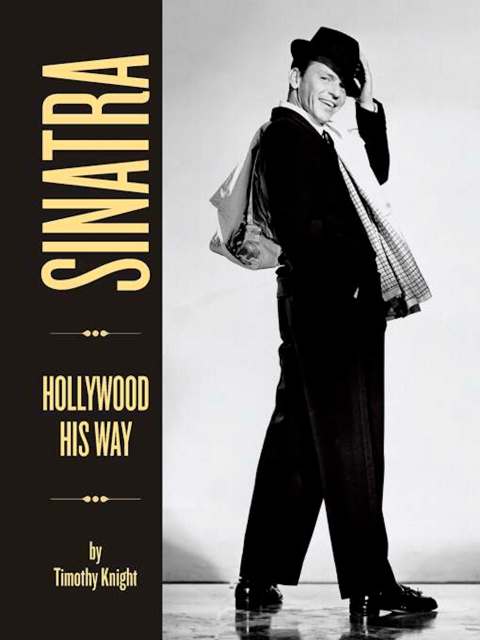

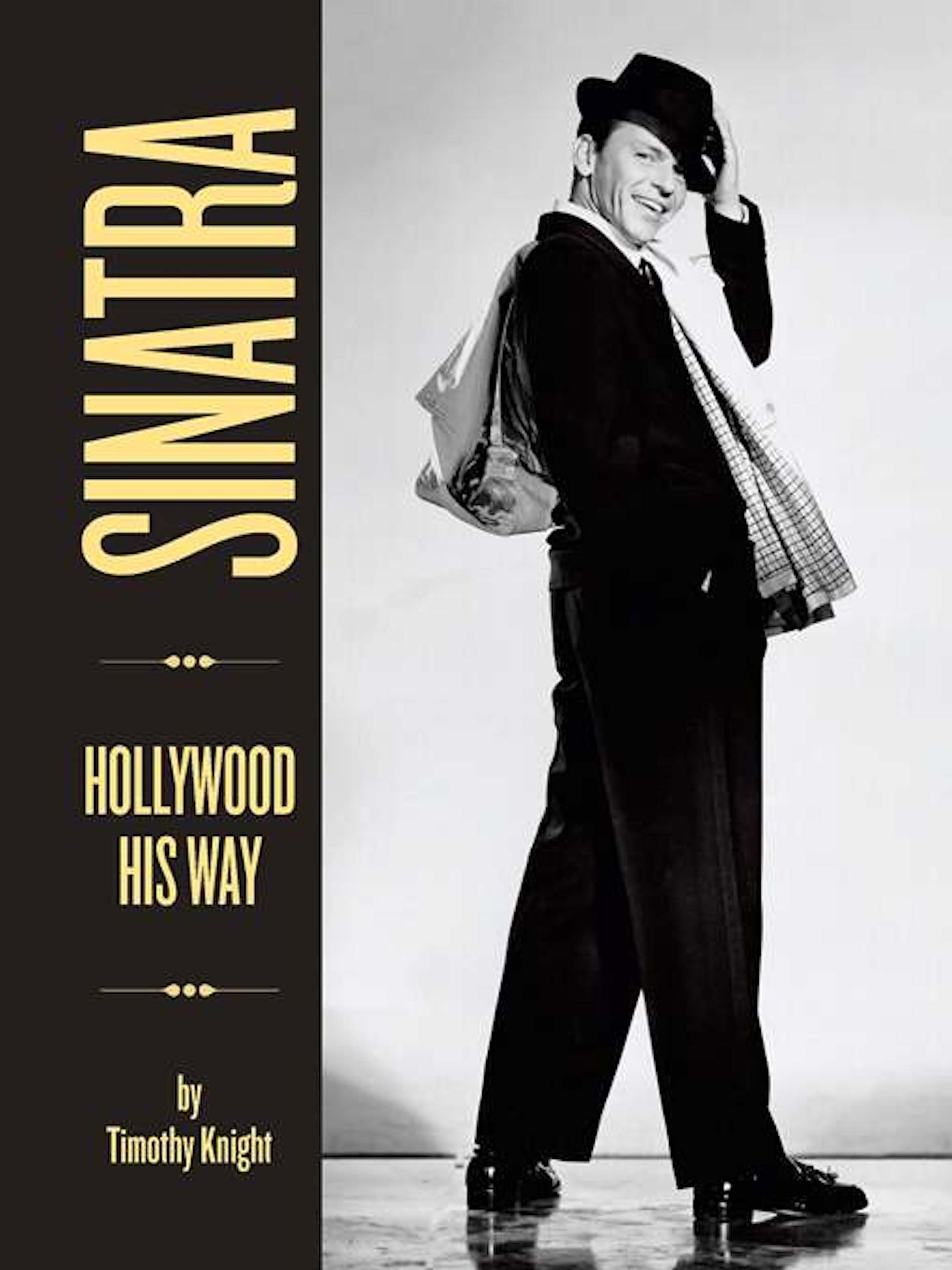

Sinatra

Hollywood His Way

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 12, 2010

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762441747

Price

$23.99Price

$30.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $23.99 $30.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 12, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

But Sinatra was much more than a music icon. He was also one of the most popular movie stars of the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s — an Academy-Award winning actor with some sixty film credits to his name. He starred in some of the most iconic films of the twentieth century and with some of the biggest names of the day. There were his dancing days with Gene Kelly in Anchors Aweigh and On the Town; his acclaimed dramatic turns in From Here to Eternity and The Manchurian Candidate; and his signature Rat Pack movies such as Ocean’s Eleven.

Sinatra: Hollywood His Way is a complete, film by film exploration of this true Hollywood legend. His screen history is vividly brought to life through illuminating reviews, behind-the-scenes stories, and hundreds of rare color and black-and-white photographs, making this the ultimate guide to the films of Frank Sinatra and an essential in the library of any fan.

Genre:

-

Library Journal, Oct 2010

"This highly enjoyable, well-written treat belongs in any library and in the hands of all fans of Frank Sinatra."

Connecticut Post, 10/21/10

…a beautiful, oversized volume “Sinatra: Hollywood His Way” that charts the amazing highs and devastating lows of the performer’s 39-year movie career… a wonderful photographic scrapbook of the singer-actor’s entire output, with smart text by Knight.American Profile, November 2010

“…offers an engrossing, entertaining, photo-packed tribute to his 41 years as a movie star.”Buffalo News, 11/28/10

“a lavish coffee-table book”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use