Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

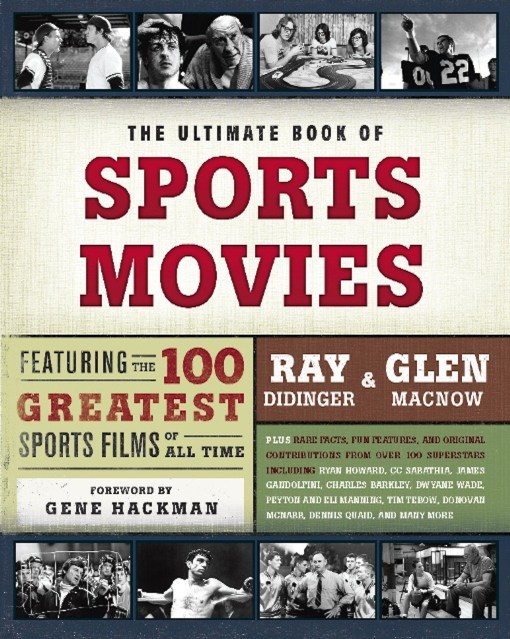

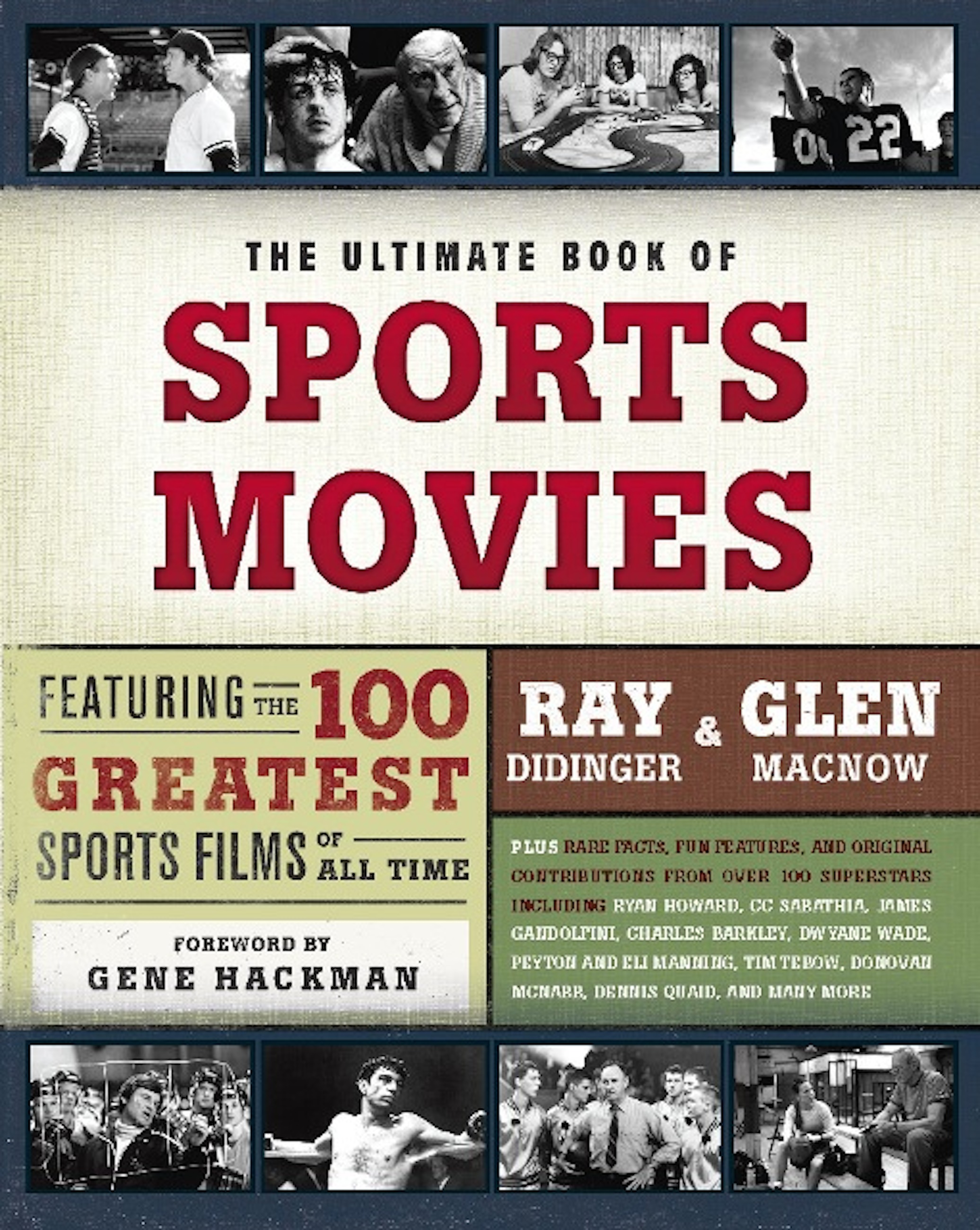

The Ultimate Book of Sports Movies

Featuring the 100 Greatest Sports Films of All Time

Contributors

By Ray Didinger

By Glen Macnow

Foreword by Gene Hackman

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $11.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 22, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Now, two nationally renowned sports media personalities take on the task of ranking the top 100 sports movies of all time, including entertaining and informative lists, special features, and contributions from over 75 top sports figures. From drama to comedy to tragedy to documentary, all the greatest sports films are here, brought to life through detailed summaries, fun facts and trivia, behind-the-scenes revelations, plus images from the greatest moments in sports film history.

Original comments from some of the top personalities in sports and entertainment — including Peyton and Eli Manning, Charles Barkley, Tony Romo, James Gandolfini, Bill Parcells, Dennis Quaid, Arnold Palmer, and many more — provide further insight and marketing punch.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 22, 2009

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762439218

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use