By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

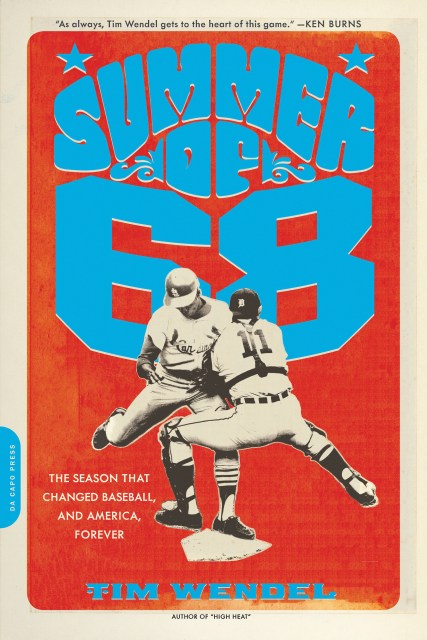

Summer of ’68

The Season That Changed Baseball -- and America -- Forever

Contributors

By Tim Wendel

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 12, 2013

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306821837

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 12, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From the beginning, ’68 was a season rocked by national tragedy and sweeping change. Opening Day was postponed and later played in the shadow of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s funeral. That summer, as the pennant races were heating up, the assassination of Robert Kennedy was later followed by rioting at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. But even as tensions boiled over and violence spilled into the streets, something remarkable was happening in major league ballparks across the country. Pitchers were dominating like never before, and with records falling and shut-outs mounting, many began hailing ’68 as “The Year of the Pitcher.”

In Summer of ’68, Tim Wendel takes us on a wild ride through a season that saw such legends as Bob Gibson, Denny McLain, Don Drysdale, and Luis Tiant set new standards for excellence on the mound, each chasing perfection against the backdrop of one of the most divisive and turbulent years in American history. For some players, baseball would become an insular retreat from the turmoil encircling them that season, but for a select few, including Gibson and the defending champion St. Louis Cardinals, the conflicts of ’68 would spur their performances to incredible heights and set the stage for their own run at history.

Meanwhile in Detroit — which had burned just the summer before during one of the worst riots in American history — ’68 instead found the city rallying together behind a colorful Tigers team led by McLain, Mickey Lolich, Willie Horton, and Al Kaline. The Tigers would finish atop the American League, setting themselves on a highly anticipated collision course with Gibson’s Cardinals. And with both teams’ seasons culminating in a thrilling World Series for the ages — one team playing to establish a dynasty, the other fighting to help pull a city from the ashes — what ultimately lay at stake was something even larger: baseball’s place in a rapidly changing America that would never be the same.

In vivid, novelistic detail, Summer of ’68 tells the story of this unforgettable season — the last before rule changes and expansion would alter baseball forever — when the country was captivated by the national pastime at the moment it needed the game most.

-

“Summer of '68 shows that imperfect men can approach baseball perfection…Wendel recounts this matchless season with verve and you-are-there immediacy.” Grand Rapids Press, 4/4/12“A welcome memoir of a year the Tigers won the World Series while the world fell apart.” Detroit Metro Times, 4/4/12“[Wendel's] writing flows and it's an easy read…He nails what's best about the sport.” Blogcritics.org, 4/3/12“Wendel's analysis of the existing literature, newsreels, and his player interviews from that season give readers a taste of the turbulence while keeping the reader interested and turning pages.” BleacherReport.com, 3/11/12“A look back at one specific baseball season and the events in the culture surrounding it.”Shelf Awareness, 4/13

“A mesmerizing story.”Metro New York, 4/10“If you're looking for the combination of the greatest year of baseball and most incendiary in American culture, here's your winner.” Houston Chronicle, 4/8 -

“A well-written, fast moving book…It would be useful for those who did not live through The Sixties to take a look back; it is useful for those of us who did to be reminded.” PopMatters.com, 3/16/12“[Wendel] tells the story…with verve, in the familiar cadences found in sports journalism. While the details of most of this book will understandably appeal to baseball fans, the added angle of how teams and players faced unrest in their own cities, and how they contended with each other on teams as well as on the field against their rivals, enriches this presentation.” Niagara Gazette, 3/8/12“A masterwork of sports sociology.” Gazalapalooza(blog), 3/14/12

“Much more than strictly a book about the momentous baseball season of 1968. It's really a thoughtful and intriguing book about our whole world during that tumultuous year, and how the pivotal social, cultural and political events inside sports and out in 1968 echo loudly to this very day…An excellent and gripping true story.” Seamheads.com, 3/20/12

-

“A wonderful book…[that] vividly recalls both a classic seven-game World Series and the political and social events that surrounded it.” WomanAroundTown.com, 5/10/12

“Wendel does a masterful job of relating all the extraordinary events that year through baseball…Buy this book now, and next time you need a gift for that baseball nut in your life, you'll have it ready to give.” Iron Mountain Daily News, 5/26/12“Delivers a brilliant summary of that tumultuous year in America…Plenty of good information here for sports fans and historians.” “The Bookworm Sez” nationally syndicated column

“[A] story of one baseball season and the players that made it fantastic, even as the world seemed to be falling apart…[A] home run!” Iron Mountain Daily News, 5/29/12

“In detailing how this season was more memorable than perhaps any other, Summer of ‘68 illustrates the deep connection between America and its national game.” NY Sports Day, 6/9/12 -

“In 1968 baseball's golden era…went out with the bang of Bob Gibson and Mickey Lolich fighting it out in one of the great pitching duels ever, one that played out in the final game game of the '68 World Series…Tim Wendel's new book does that watershed moment justice and I found it deeply affecting…There are those rare occasions when sweeping change to the wider world walks in tandem with baseball, as it did in 1968. Tim Wendel's book captures the spirit of those times, the way that great players were humbled by the loss of their own heroes, how they recovered–as did the nation–and how they gained new strength to achieve greatness and walk away winners.”Booklist, 4/15/12

“Wendel details a terrific World Series…and he brings into relief the players, influenced by the political climate or not, who had a profound impact on the game.”Tampa Tribune, 3/26/12“Wendel does a masterful job of putting sports and politics in their proper perspective…Wendel catches all the emotions of 1968 and has written a book that is as memorable as the year he chronicles.” Redbird Rants (website), 3/26/12

“A must read for Cardinals' and baseball fans alike.” USAToday.com, 4/5/12 -

“No book better captures how in 1968 sports changed America—and vice versa. In splendid fashion, Tim Wendel takes us on a rollicking journey through an unparalleled year of tumult, tragedy, and, too, joy. Summer of '68 reads like a novel brimming with surprising action, colorful characters, and fresh insights. I enjoyed every page.”John Thorn, Official Historian of Major League Baseball and author of Baseball in the Garden of Eden

“It seems like only yesterday when both our nation and its pastime seemed in mortal peril. Tim Wendel's Summer of '68 brilliantly evokes the glories and the grim realities of that time, when America and baseball came to a crossroads, and emerged for the better on the other side.”Library Journal, 2/1/12

-

“The story of one baseball season and the players that made it fantastic, even as the world seemed to be falling apart around the field.” Charleston Post and Courier, 4/15/12

“Wendel consistently gets to the heart of a changing world.” Bookviews (blog), May 2012“Wendel captures the spirit of the time and weaves together the stories of the year's events, the teams and players in a thoroughly entertaining fashion; particularly for anyone who loves the game. This book demonstrates the deep connection between the nation and its national game.” Bookgasm.com, 4/30/12

“An exciting look at the year in MLB…There is real value here. It's instructive to learn what players of the time thought about historical and newsworthy events, and how some even had first-hand participation…If you're a baseball fan who remembers the glory days of Bob Gibson's frightening stare, the showbiz glitz of Denny McLain, the time when a manager could actually be named Mayo Smith, then you should enjoy Summer of '68.”SpliceToday.com, 5/10/12

“A splendid, cross-generational book that can satisfy not only the duffers who remember that year like it was yesterday, but also young and inquisitive baseball fans and history students.”Memphis Commercial Appeal, 5/12/12

-

“Wendel has interviewed many of the key participants to bring this crucial year to life. Transcending baseball history alone, this is recommended for baseball fans and students of the era.”Kirkus Reviews, 2/15/12

“[Wendel] charts the thrilling Series game by game. More intriguing, though, is the season's unique backdrop: the ‘Year of the Pitcher' in baseball and the national turmoil surrounding the sports world…An appealing mix of baseball and cultural history.” Publishers Weekly, 2/20/12“Wendel mines one of baseball's more absorbing episodes in this rich chronicle of the 1968 season. It's a sociologically resonant account…Wendel provides telling color commentary…and sharp analyses of on-field strategizing and play-by-play.” Cardial70.com, 2/6/12

“Wendel doesn't disappoint in Summer of '68…especially if you are a fan of the pitching side of the game…this is going to be a book that you are going to want on your bookshelf if you are a fan of baseball history in general or Cardinal history in specific. It's a quick and entertaining read and one that you'll probably come back to time and time again.” Relaxed Fit e-zine, 2/22/12

-

“Wendel is one of the best baseball book writers…In Summer of '68 he has a great subject…Wendel does a fine job of relating the tensions that were coursing through baseball at the time, set against the backdrop of national and international turmoil.” BaseballReflections.com, 4/2

“Wendel meticulously tells the story of many of the players from both squads giving the reader a comprehensive understanding of how the 1968 Series came to be from many different perspectives…The extensive research that Wendel must have done in order to get the insight and perspective shared in this book is evident on every page. Even people who don't know much about baseball history may come off as an expert on this season after reading this book.” New York Journal of Books“Not only the story about the 1968 Major League Baseball season, but also a meticulous history lesson outlining the dawning of a new age in baseball—and in American history…Mr. Wendel engagingly presents the facts of what was a game-changing year in American history for baseball, but most importantly for the citizens of America who could see there was a wrong to right—and it was up to us to achieve that change.” Detroit Free Press, 4/15/12 -

“[From] a dugout's worth of new books about baseball…[one] of this season's most promising literary prospects…A look back at 1968, the year of political assassinations, urban riots and a classic World Series.” New York Post, 4/1/12 “Wendel shows that baseball really is part of the fabric of America.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 4/1/12“Cardinals fans who want to revisit the team's collapse and loss against the Tigers in the World Series will probably appreciate Wendel's detailed description in Summer of '68.” Cleveland Sunday Plain Dealer, 4/1/12“[Wendel] astutely marks this summer as a landmark year for baseball—the game, like the country, would be forever changed.” San Antonio Express-News, 4/2/12“Nostalgic, sure, but never sentimental or sappy, Wendel…sets a grand stage for a crucial year in sports, and produces an engaging, well-researched book that baseball fans can breeze through easily…If you miss players like Lou Brock and Luis Tiant, Summer of '68 will remind you why.” Milwaukee Sunday Journal Sentinel, 4/1/12“Engaging…Bring[s] the season alive.” San Diego Union-Tribune, 4/1/12

-

“[Wendel is] a passionate fan with the skill of a reporter…Summer of '68 isn't a book about Detroit; it is bigger than that. But that year, the story of Tigers baseball resonated beyond the city's borders. Wendel ably captures both how, and why, it mattered so much.” Lansing City Pulse, 4/11/12“Wendel's book serves as a testament to a team that is credited with holding a city together and giving its residents something to cheer about after the devastating 1967 riots…Wendell also makes the case that the 1968 series represented the last pure games of baseball in a time before league playoffs and wild-card spots.” Tonawanda News, 4/15/12

“The year 1968 was the bellwether for a lot of things, including baseball's dominance over football and society's admission that serious changes were in the wind. Wendel addresses it well.”

American Profile, 4/28/12“This riveting account masterfully weaves the social turbulence of 1968 into a narrative of one of the game's most memorable seasons.” McClatchy-Tribune News Service, 4/26/12“Wendel is a master storyteller…Wendel skillfully ties the baseball season to domestic events.” Savannah Morning News, 4/18/12 -

Ken Burns, filmmaker, creator of the Emmy Award–winning documentary series Baseball

“As always, Tim Wendel gets to the heart of this game and the complicated republic it so precisely mirrors.”David Maraniss, author of Clemente and When Pride Still Mattered

“Summer of '68 captivated me from the get-go: I was eighteen that summer, reeling from the chaos of an unforgettable year, awestruck by the ferocious beauty of Bob Gibson, rooting for Willie Horton and the Tigers from the city of my birth. Cheers to Tim Wendel for bringing it all back so vividly.”Hampton Sides, author of Hellhound on His Trail

“A year of great convulsion and heartbreak, 1968 was the closest we've come to a national nervous breakdown since the Civil War. But as Tim Wendel so deftly captures in this fine book, it was also a year when baseball soothed and thrilled us—and urgently reminded us why it's called the ‘national pastime.'”Tom Stanton, author of The Final Season and Ty and The Babe

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use