By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

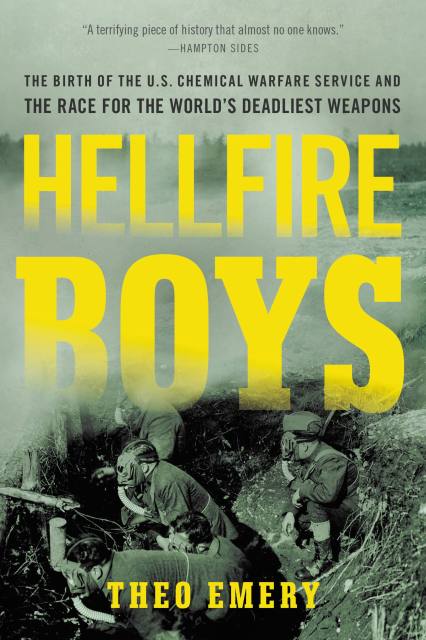

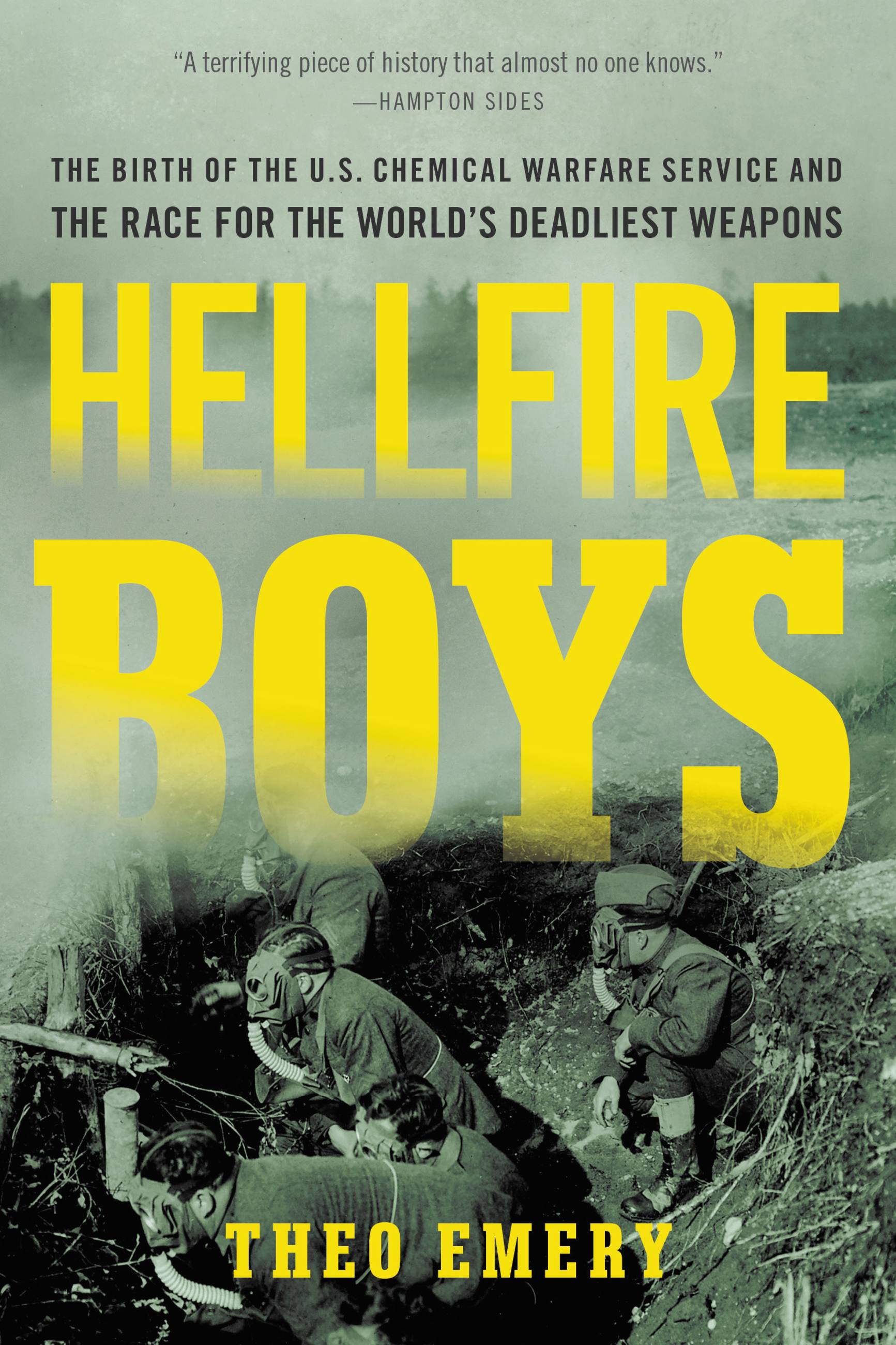

Hellfire Boys

The Birth of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service and the Race for the World¿s Deadliest Weapons

Contributors

By Theo Emery

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 14, 2017

- Page Count

- 560 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316264112

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $25.99 $33.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 14, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In 1915, when German forces executed the first successful gas attack of World War I, the world watched in horror as the boundaries of warfare were forever changed. Cries of barbarianism rang throughout Europe, yet Allied nations immediately jumped into the fray, kickstarting an arms race that would redefine a war already steeped in unimaginable horror.

Largely forgotten in the confines of history, the development of the U.S. Chemical Warfare Service in 1917 left an indelible imprint on World War I. This small yet powerful division, along with the burgeoning Bureau of Mines, assembled research and military unites devoted solely to chemical weaponry, outfitting regiments with hastily made gas-resistant uniforms and recruiting scientists and engineers from around the world into the fight.

As the threat of new gases and more destructive chemicals grew stronger, the chemists’ secret work in the laboratories transformed into an explosive fusion of steel, science, and gas on the battlefield. Drawing from years of research, Theo Emery brilliantly shows how World War I quickly spiraled into a chemists’ war, one led by the companies of young American engineers-turned-soldiers who would soon become known as the “Hellfire Boys.” As gas attacks began to mark the heaviest and most devastating battles, these brave and brilliant men were on the front lines, racing against the clock — and the Germans — to protect, develop, and unleash the latest weapons of mass destruction.

-

One of Hello Giggles' "Top Books to Get Your Dad for Christmas"

-

Praise for Hellfire BoysHampton Sides, New York Times bestselling author of In the Kingdom of Ice, Ghost Soldiers, Hellhound on His Trail, and Blood and Thunder

"Through dogged reporting and a clear-eyed journey back through a world of secrets that are literally toxic, Theo Emery has dispassionately constructed an astonishing narrative of the scientists and soldiers who were tasked with winning a horrible war a century ago. Refusing to allow our modern revulsion of chemical weapons (however well-founded) to shape his extraordinary narrative, Emery--like all good historians--is determined to let the era of his subject speak for itself." -

"A fascinating and deeply researched account of how America reinvented its military--and itself--in its first modern global war. Theo Emery combines science, history, and character-driven drama to illuminate some of the darkest aspects of our national past."Beverly Gage, author of The Day Wall Street Exploded and Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University

-

"Brims with shock and surprise... Through squarely a crackling history, Hellfire Boys is also a relevant primer on the past 100 years and on a kind of total warmaking that continues to haunt us--sometimes from another hemisphere, sometimes in our own back yard."Dan Zak, Washington Post

-

"Moving crisply between stateside turf wars and battlefront combat, this well-written and well-researched slice of history will appeal to virtually any history or war buff."Library Journal (starred review)

-

"Even military buffs will learn from this intensely researched, often unnerving account.... Readers will share Emery's lack of nostalgia for this half-forgotten weapon, but they will admire this satisfying combination of technical background, battlefield fireworks, biographies of colorful major figures, and personal anecdotes from individual soldiers."Kirkus

-

"Journalist Emery offers a useful and absorbing reminder that, a century earlier, it was a different weapon of mass destruction that terrified both soldiers and civilians... This is a timely and often unsettling examination of a previously well-hidden government program."Booklist

-

"Illuminating... Emery zeroes in on a little-known and sparsely documented moment in the history of chemical warfare."The National Book Rivew

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use