By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

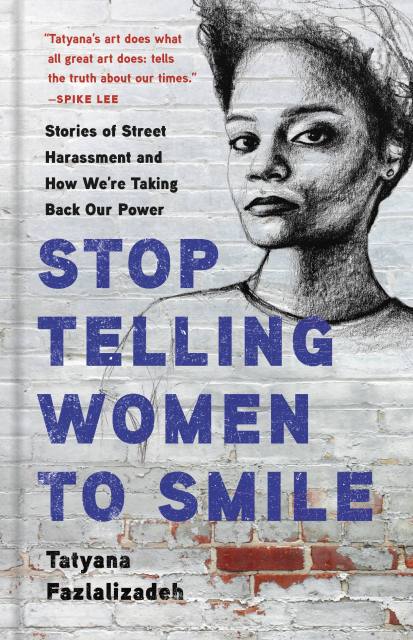

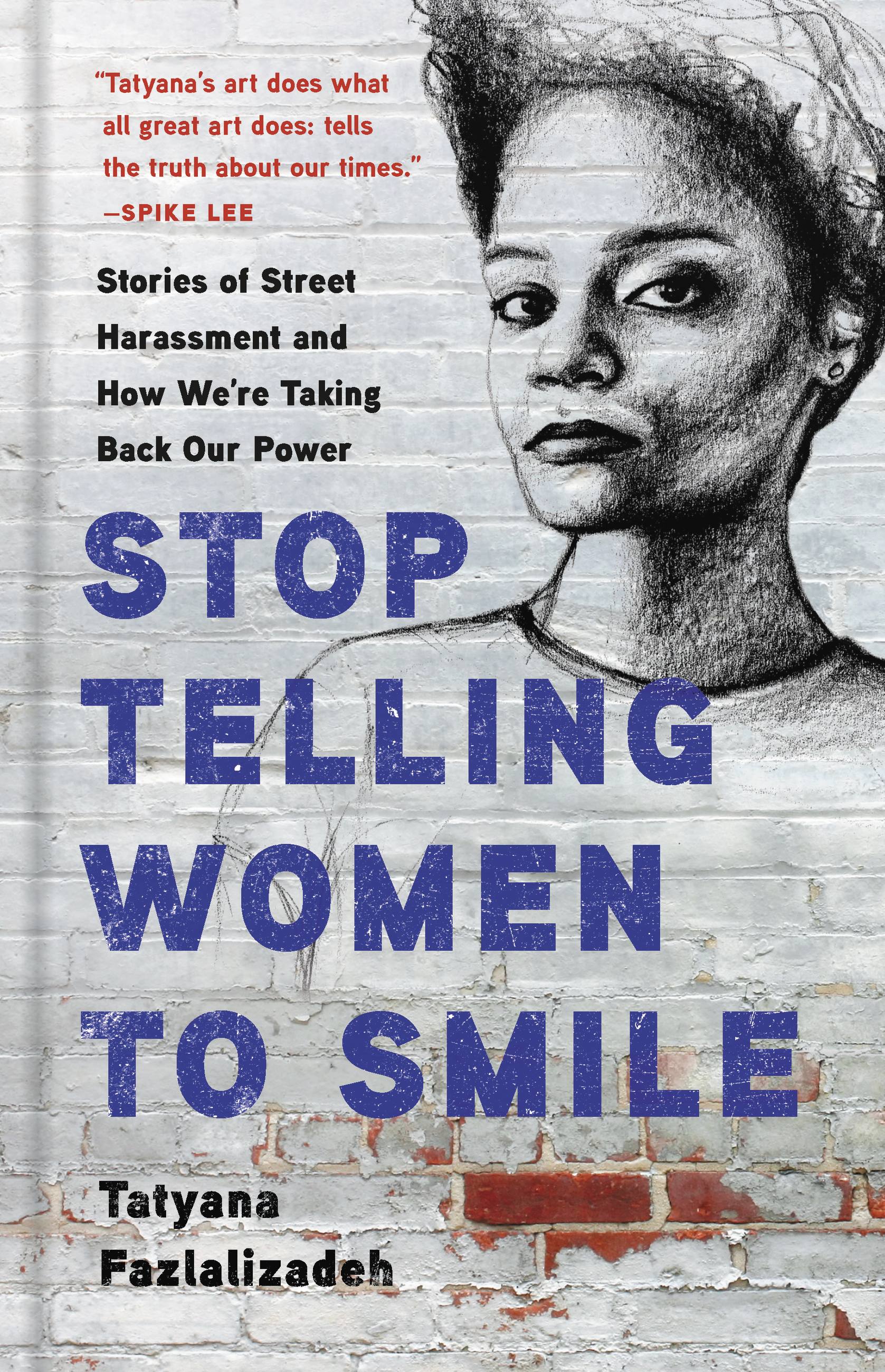

Stop Telling Women to Smile

Stories of Street Harassment and How We're Taking Back Our Power

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 4, 2020

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580058476

Price

$16.99Price

$21.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 4, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The debut book from a celebrated artist on the urgent topic of street harassment

Every day, all over the world, women are catcalled and denigrated simply for walking down the street. Boys will be boys, women have been told for generations, ignore it, shrug it off, take it as a compliment. But the harassment has real consequences for women: in the fear it instills and the shame they are made to feel.

In Stop Telling Women to Smile, Tatyana Fazlalizadeh uses her arresting street art portraits to explore how women experience hostility in communities that are supposed to be homes. She addresses the pervasiveness of street harassment, its effects, and the kinds of activism that can serve to counter it. The result is a cathartic reckoning with the aggression women endure, and an examination of what equality truly entails.

Every day, all over the world, women are catcalled and denigrated simply for walking down the street. Boys will be boys, women have been told for generations, ignore it, shrug it off, take it as a compliment. But the harassment has real consequences for women: in the fear it instills and the shame they are made to feel.

In Stop Telling Women to Smile, Tatyana Fazlalizadeh uses her arresting street art portraits to explore how women experience hostility in communities that are supposed to be homes. She addresses the pervasiveness of street harassment, its effects, and the kinds of activism that can serve to counter it. The result is a cathartic reckoning with the aggression women endure, and an examination of what equality truly entails.

-

"Tatyana's art does what all great art does: tells the truth about our times. Her portraits of women are not only beautiful, they give women a space to have their truths heard. She is formidable and strong in her art, and our society is better for it."Spike Lee

-

"Tatyana Fazlalizadeh has done what so many artists wish to accomplish. She has combined her tremendous talent for producing beautiful images with a forthright critique of the world she inhabits. Stop Telling Women to Smile is the most consequential street art campaign of the last decade, and we owe that to Tatyana's honesty, intelligence, hustle, and unmatched artistic talents. Her commitment to this project has challenged the way we discuss women and women's bodies in public space, and we are better for it."Mychal Denzel Smith, New York Times bestselling author of Invisible Man: Got the Whole World Watching

-

"Tatyana Fazlalizadeh's work wrestles the knot between cultural codes and the bodies of women with spectacular artistry. Her intersectional feminism lights the fire we need to see a way forward. She is unflinching and glorious."Lidia Yuknavitch, bestselling author of The Book of Joan

-

"Tatyana Fazlalizadeh's work makes me smile. Provocation brings joy and Fazlalizadeh's images startle and prod with their delicate ferocity, reminding us that women are human. She treats us to what is seldom seen: woman as subject, woman as agent, woman as free human being."Myriam Gurba, author of Mean

-

"Tatyana Fazlalizadeh is the political artist of our time. Her walls burn, laying plain oppressions both buried and overt with beauty, power, and courage."Molly Crabapple, author of Drawing Blood

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use