By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

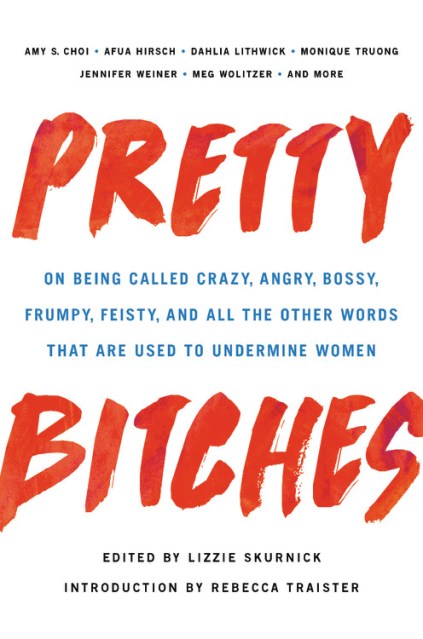

Pretty Bitches

On Being Called Crazy, Angry, Bossy, Frumpy, Feisty, and All the Other Words That Are Used to Undermine Women

Contributors

Introduction by Rebecca Traister

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 3, 2020

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580059190

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 3, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

No one knows this better than Lizzie Skurnick, writer of the New York Times’ column “That Should be A Word”and a veritable queen of cultural coinage. And in Pretty Bitches, Skurnick has rounded up a group of powerhouse women writers to take on the hidden meanings of these words, and how they can limit our worlds — or liberate them.

From Laura Lipmann and Meg Wolizer to Jennifer Weiner and Rebecca Traister, each writer uses her word as a vehicle for memoir, cultural commentary, critique, or all three. Spanning the street, the bedroom, the voting booth, and the workplace, these simple words have huge stories behind them — stories it’s time to examine, re-imagine, and change.

-

"Clever and potent.... The book's smart premise and the incisive essays themselves are immensely relatable and should provide a great catalyst for personal introspection and thoughtful and productive discussion."Booklist (starred review)

-

"Sharp-witted and intimate.... An eloquent inquiry into how language enshrines gender stereotypes."Publishers Weekly

-

"This uplifting collection serves as a good first step toward highlighting what's wrong with how women are talked about.... A galvanizing, sharp compendium."Kirkus

-

"Note to men: When you describe an ex-girlfriend or wife 'crazy,' all it tells me is that you're an emotional idiot. Note to women: This great new book by Lizzie Skurnick recasts the various insults directed at us for decades and centuries, breathing confident life into what it means to be an unabashed, bossy, crazy-ass bitch."Anna Holmes, founder of Jezebel and editor of The Book of Jezebel: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Lady Things and Hell Hath No Fury: Women's Letters from the End of the Affair

-

"This book is hilarious, amazing, and inspiring. An incredible anthology of brilliant women. Buy this book today, preferably more than one copy."Molly Jong-Fast, author of The Social Climber's Handbook and Girl [Maladjusted]: True Stories from a Semi-Celebrity Childhood

-

"Lizzie Skurnick has been the go to person for words for as long as I can remember. Now, she has gone even further, redefining the way we use them. This collection of breathtaking essays shows how seemingly innocuous words (and some pretty ugly ones, too) were once used to keep women down -- but not anymore. Take that, mansplainers. Pretty Bitches is truly something."Marcy Dermansky, author of Very Nice and The Red Car

-

"Funny, trenchant, moving, breathtaking -- the essays here remake a language that has been used so often to trap women so that it can free them instead. A prismatic look at the state of being a woman today, from some of our best living writers."Alexander Chee, author of Edinburgh, The Queen of the Night, and How to Write an Autobiographical Novel

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use