By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

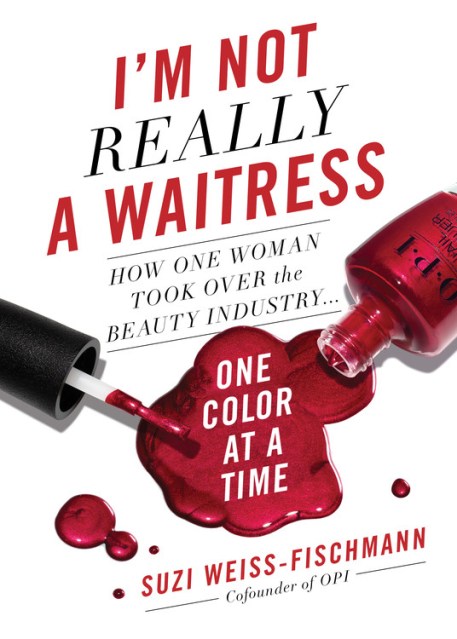

I’m Not Really a Waitress

How One Woman Took Over the Beauty Industry One Color at a Time

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 12, 2019

- Page Count

- 240 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580058193

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 12, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In I’m Not Really a Waitress–titled after OPI’s top-selling nail color–Suzi reveals the events that led her family to flee Communist Hungary and eventually come to New York City in pursuit of the American dream. She shares how those early experiences gave rise to OPI’s revolutionary vision of freedom and empowerment, and how Suzi transformed an industry by celebrating the power of color-and of women themselves.

-

"Suzi Weiss-Fischmann set out to create a red polish that every woman could wear, and with I'm Not Really a Waitress, she nailed it."Allure

-

"Meet Suzi Weiss-Fischmann, the brains and bravado behind the brand's trend-sparking shades."Martha Stewart Living

-

"So you're at your standing manicure appointment trying to decide between You Don't Know Jacques! and Lincoln Park After Dark, and you find yourself wondering: Who is the creative mind who comes up with these fantastically punny nail polish color names? Mystery solved: It's Suzi Weiss-Fischmann."Cosmopolitan

-

"The woman who has shaped the way we do nails is Suzi Weiss-Fischmann."Los Angeles Times

-

"Suzi's such a fierce female entrepreneur."Kerry Washington in WWD

-

"[Suzi Weiss-Fischmann] is just as rad as you think she'd be."Elite Daily

-

"Suzi is a true risk taker, right down to her perfectly manicured tippy toes."Family Circle

-

"The average person can't detect the difference between berry and burgundy or tell fuchsia from hot pink. It takes an exceptional eye and special sensibility to recognize the exact shade of scarlet that women all over the world will be swooning over next season. Suzi Weiss-Fischmann has spent a lifetime doing just that, season after season, year after year and created a brand that's now the most recognized and revered in the world."Vogue India

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use