Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

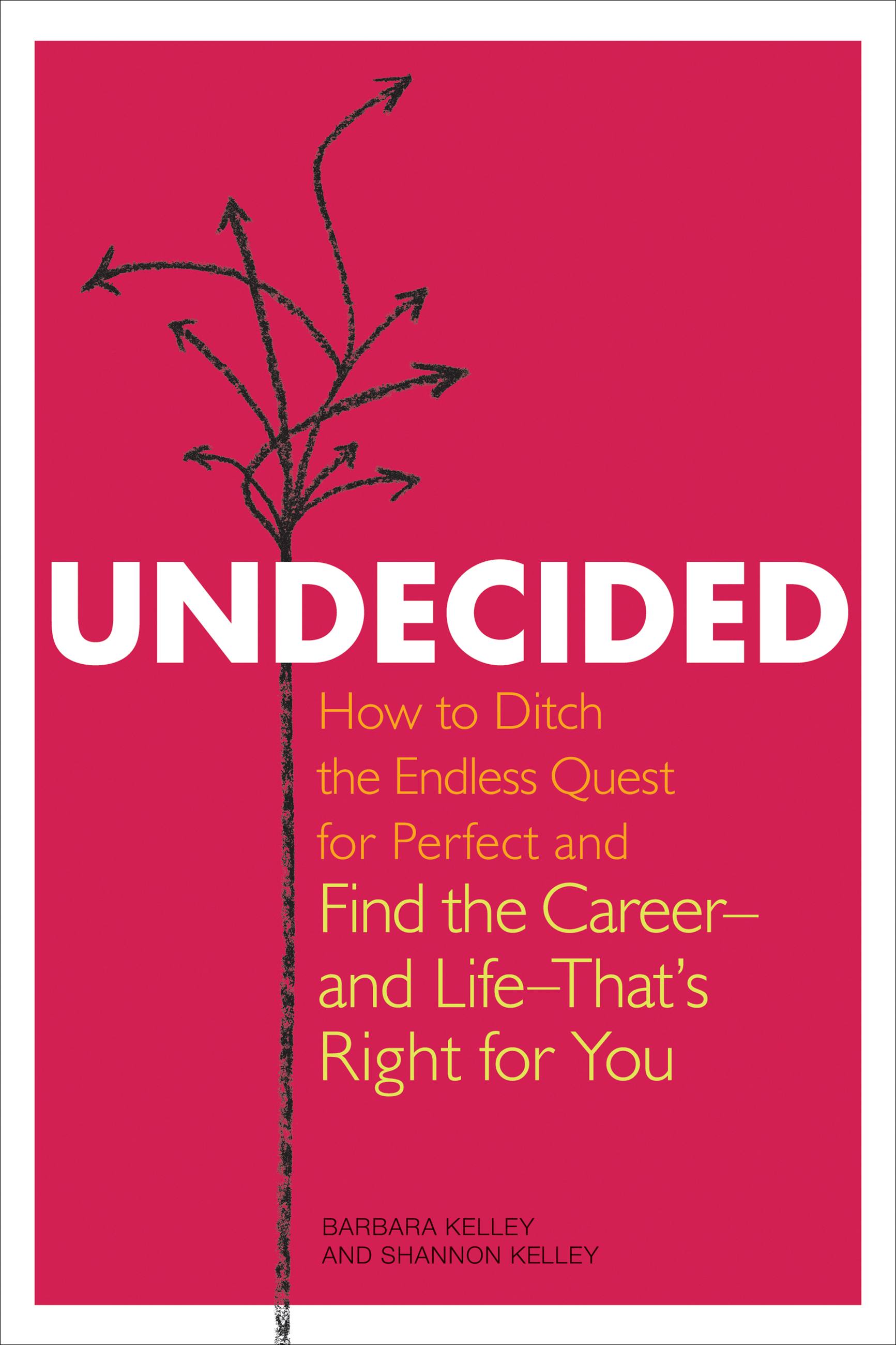

Undecided

How to Ditch the Endless Quest for Perfect and Find the Career -- and Life --That's Right for You

Contributors

By Shannon Kelley

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 26, 2011

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580053419

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 26, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In a world of unprecedented opportunity—and pressure—women are struggling more than ever to make career decisions and move forward without second-guessing themselves. Young women graduate from college and believe they have to find the perfect path and then can’t decide which way to go.

Undecided is an invaluable guide to this cultural phenomenon of “analysis paralysis.” Looking at both what the media and academic studies have reported on women, careers, and particularly the undecided phenomenon—as well as personal accounts from numerous women—mother and daughter Barbara and Shannon Kelley discuss how we got to this frustrating place, why it affects women in particular, and how today’s culture fuels our fears and distractions.

The Kelleys cast a critical eye upon the psychology behind the pressure to choose, and they argue that if women are going to succeed in rising above the often-crippling demands of the modern world they need to take action . . . starting with a serious shift in perspective.