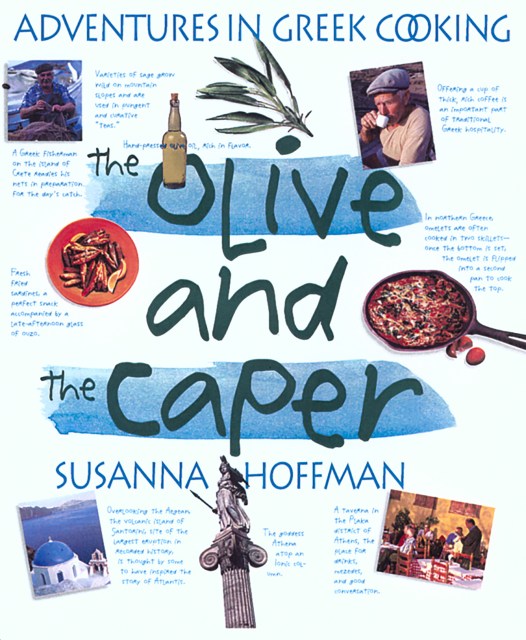

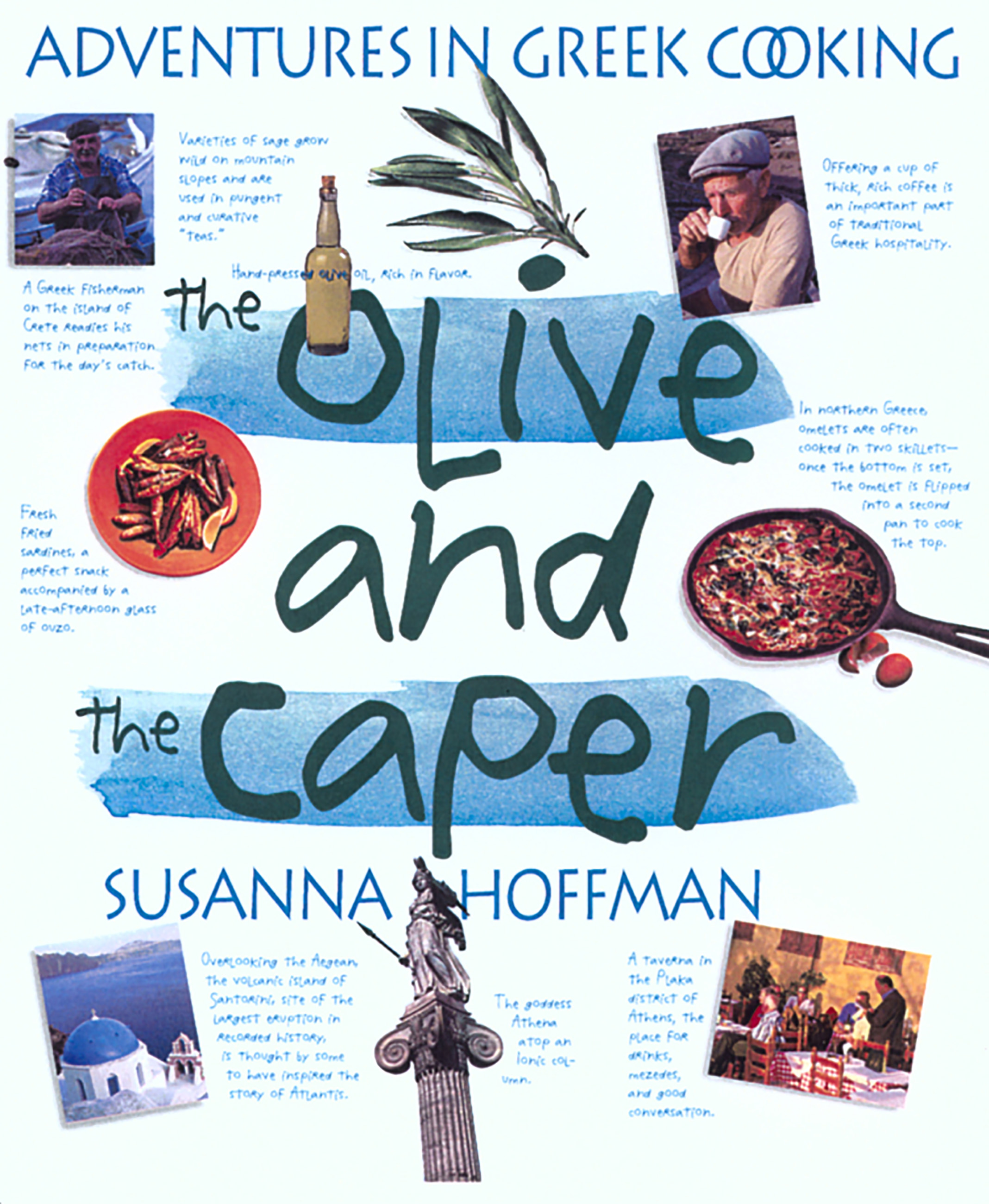

The Olive and the Caper

Adventures in Greek Cooking

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $18.99 $24.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 1, 2004. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

This is the year “It’s Greek to me” becomes the happy answer to what’s for dinner. My Big Fat Greek Wedding, the upcoming epic Troy, the 2004 Summer Olympics returning to Athens–and now, yet another reason to embrace all things Greek: The Olive and the Caper, Susanna Hoffman’s 700-plus-page serendipity of recipes and adventure.

In Corfu, Ms. Hoffman and a taverna owner cook shrimp fresh from the trap–and for us she offers the boldly-flavored Shrimp with Fennel, Green Olives, Red Onion, and White Wine. She gathers wild greens and herbs with neighbors, inspiring Big Beans with Thyme and Parsley, and Field Greens and Ouzo Pie. She learns the secret to chewy country bread from the baker on Santorini and translates it for American kitchens. Including 325 recipes developed in collaboration with Victoria Wise (her co-author on The Well-Filled Tortilla Cookbook, with over 258,000 copies in print), The Olive and the Caper celebrates all things Greek: Chicken Neo-Avgolemeno. Fall-off-the-bone Lamb Shanks seasoned with garlic, thyme, cinnamon and coriander. Siren-like sweets, from world-renowned Baklava to uniquely Greek preserves: Rose Petal, Cherry and Grappa, Apricot and Metaxa.

In addition, it opens with a sixteen-page full-color section and has dozens of lively essays throughout the book–about the origins of Greek food, about village life, history, language, customs–making this a lively adventure in reading as well as cooking.

In Corfu, Ms. Hoffman and a taverna owner cook shrimp fresh from the trap–and for us she offers the boldly-flavored Shrimp with Fennel, Green Olives, Red Onion, and White Wine. She gathers wild greens and herbs with neighbors, inspiring Big Beans with Thyme and Parsley, and Field Greens and Ouzo Pie. She learns the secret to chewy country bread from the baker on Santorini and translates it for American kitchens. Including 325 recipes developed in collaboration with Victoria Wise (her co-author on The Well-Filled Tortilla Cookbook, with over 258,000 copies in print), The Olive and the Caper celebrates all things Greek: Chicken Neo-Avgolemeno. Fall-off-the-bone Lamb Shanks seasoned with garlic, thyme, cinnamon and coriander. Siren-like sweets, from world-renowned Baklava to uniquely Greek preserves: Rose Petal, Cherry and Grappa, Apricot and Metaxa.

In addition, it opens with a sixteen-page full-color section and has dozens of lively essays throughout the book–about the origins of Greek food, about village life, history, language, customs–making this a lively adventure in reading as well as cooking.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 1, 2004

- Page Count

- 608 pages

- Publisher

- Workman Publishing Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780761164548

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use