By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

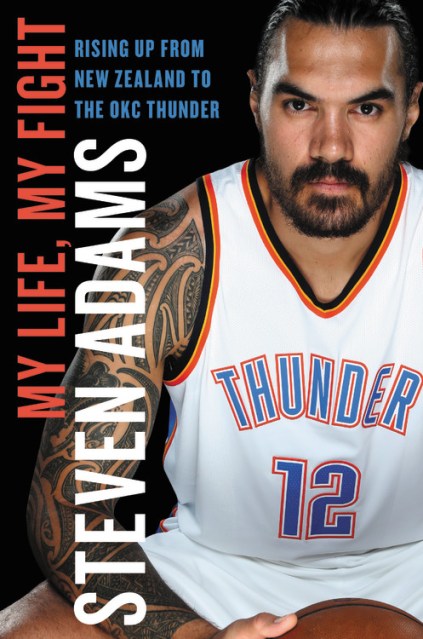

My Life, My Fight

Rising Up from New Zealand to the OKC Thunder

Contributors

By Steven Adams

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 9, 2018

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316491464

Price

$36.00Price

$47.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $36.00 $47.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 9, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Steven Adams overcame extreme odds to become a first-round prospect in the 2013 NBA draft. From there he signed a major contract with the Oklahoma City Thunder — making him New Zealand’s highest-paid athlete ever — and went on to forge a reputation for his intense, physical style of basketball.

Adams takes you inside the draft process from the fascinating whirlwind tour of pre-draft workouts with dozens of teams to the draft itself where dreams are made or dashed and the Gatorade bottles on every table are glued shut. He reveals what it’s like to be a rookie in the league, getting pushed around and elbowed — or worse. He takes the court alongside superstars like Russell Westbrook, Paul George, Carmelo Anthony, and Kevin Durant; and matches up against legendary big men like Tim Duncan, DeAndre Jordan, Dwight Howard, and Draymond Green. Adams recounts the Thunder’s rise through the victories and the heartbreaks and how the resilient team has a bright future ahead.

In this intimate account of his life story so far, the seven-foot center also reflects on his humble upbringing as one of fourteen children, the impact of his father’s death when he was just thirteen, the multiple challenges and setbacks he has faced, and what basketball means to him.

Told with warmth, humor, and humility, My Life, My Fight is a gripping account from an emerging superstar.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use