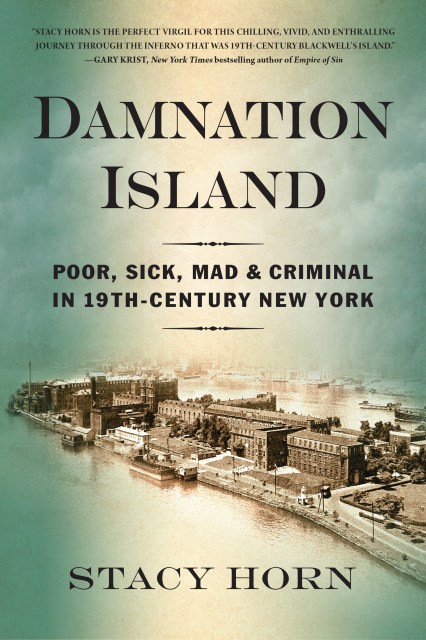

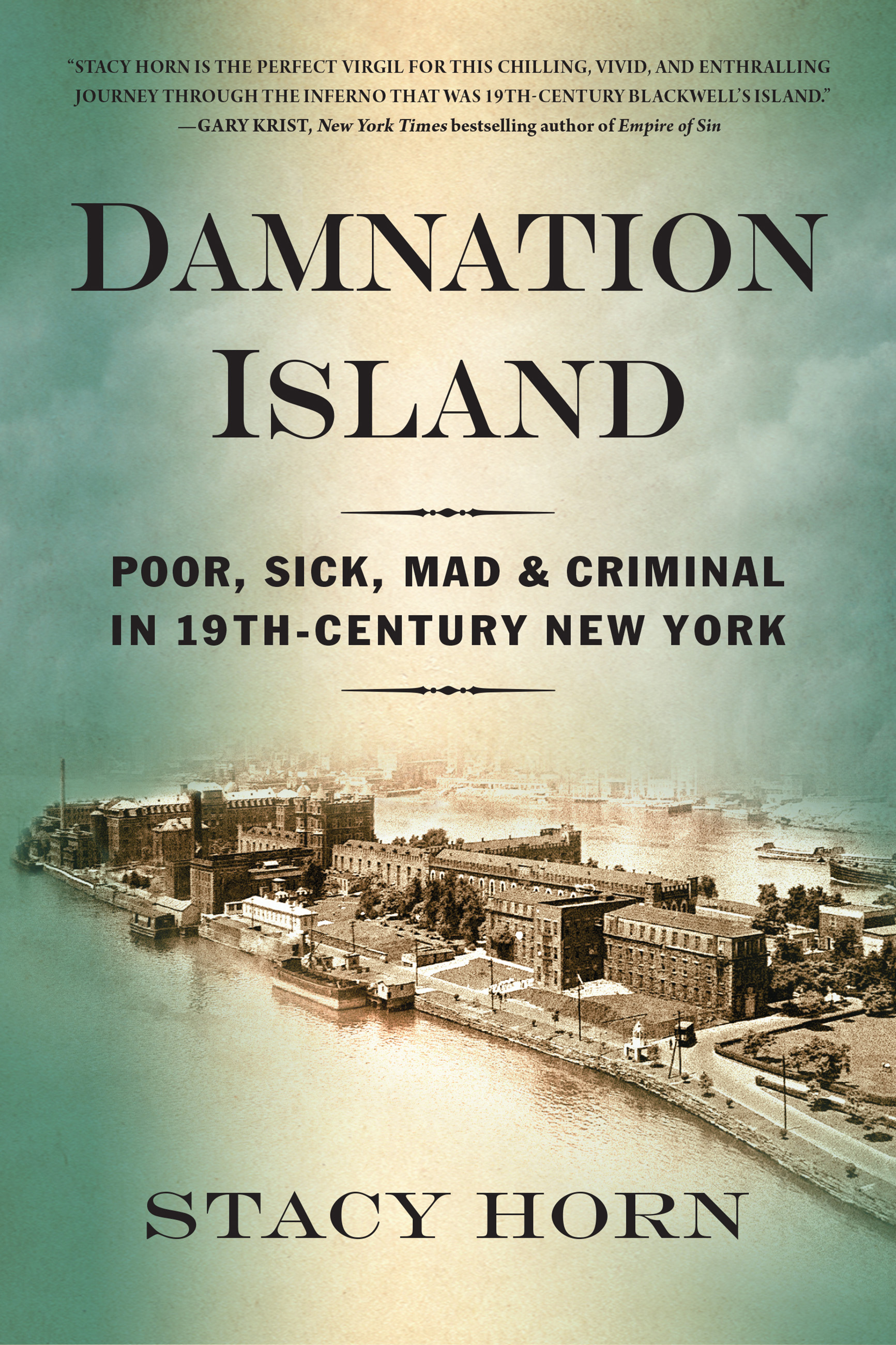

Damnation Island

Poor, Sick, Mad, and Criminal in 19th-Century New York

Contributors

By Stacy Horn

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.95 $22.95 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 15, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

"Enthralling; it is well worth the trip.” —New York Journal of Books

Conceived as the most modern, humane incarceration facility the world had ever seen, New York’s Blackwell’s Island, site of a lunatic asylum, two prisons, an almshouse, and a number of hospitals, quickly became, in the words of a visiting Charles Dickens, "a lounging, listless madhouse." Digging through city records, newspaper articles, and archival reports, Stacy Horn tells a gripping narrative through the voices of the island’s inhabitants. We also hear from the era’s officials, reformers, and journalists, including the celebrated undercover reporter Nellie Bly. And we follow the extraordinary Reverend William Glenney French as he ministers to Blackwell’s residents, battles the bureaucratic mazes of the Department of Correction and a corrupt City Hall, testifies at salacious trials, and in his diary wonders about man’s inhumanity to his fellow man. Damnation Island shows how far we’ve come in caring for the least fortunate among us—and reminds us how much work still remains.

Conceived as the most modern, humane incarceration facility the world had ever seen, New York’s Blackwell’s Island, site of a lunatic asylum, two prisons, an almshouse, and a number of hospitals, quickly became, in the words of a visiting Charles Dickens, "a lounging, listless madhouse." Digging through city records, newspaper articles, and archival reports, Stacy Horn tells a gripping narrative through the voices of the island’s inhabitants. We also hear from the era’s officials, reformers, and journalists, including the celebrated undercover reporter Nellie Bly. And we follow the extraordinary Reverend William Glenney French as he ministers to Blackwell’s residents, battles the bureaucratic mazes of the Department of Correction and a corrupt City Hall, testifies at salacious trials, and in his diary wonders about man’s inhumanity to his fellow man. Damnation Island shows how far we’ve come in caring for the least fortunate among us—and reminds us how much work still remains.

Genre:

-

“In her fine new book . . . Stacy Horn lucidly, and not without indignation, documents the island’s bleak history, detailing the political and moral failures that sustained this hell, failures still evident today in the prison at Rikers Island.”

—The New York Times Book Review

“Fast moving and entrenched in detail . . . History buffs will be terrified by what occurred [at Blackwell’s Island] a century ago.”

—BUST

“Horn creates a vivid and at times horrifying portrait of Blackwell’s Island (today’s Roosevelt Island) in New York City’s East River during the late 19th century . . . Horn has created a bleak but worthwhile depiction of institutional failure, with relevance for persistent debates over the treatment of the mentally ill and incarcerated.”

—Publishers Weekly

“This is an essential—and heartbreaking—book for readers seeking to better understand contemporary public policy.”

—Booklist, starred review

"[A] fascinating look at a piece of nearly forgotten New York City history—one that will make you thankful for modern conveniences."

—Mental Floss (Best Books of 2018)

“Horn engagingly explores a history that, perhaps surprisingly, extended into the 1960s.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Having reviewed a seemingly endless array of archival materials, Horn brings this subject to light in stunning detail. Readers will instantly see how this history continues to haunt us, as the boundaries between the four classes of people on the island (the poor, the mad, the sick and the criminal) are, in the public imagination, as blurred as ever.”

—BookPage

“Teeter-tottering between a history textbook and a murder mystery, Stacy Horn's Damnation Island is fast moving and entrenched in detail . . . What's even more horrifying—it's all real . . . These days, the island is a residential community dotted with scenic parks and landmarks. But history buffs will be terrified by what occurred there a century ago.”

—Brianne KaneforBUST

“A stunning examination of bureaucracy gone wrong, and the evolution of the place we now call Roosevelt Island.”

—Salon

“Stacy Horn has done a commendable job by shedding light on the dark corners of our history. Damnation Island is a book of history written like a novel. Every American needs to read it.”

—The Washington Book Review

“Stacy Horn's history of Blackwell’s Island is a shocking tale, and an invaluable account that will reward anyone with an interest in the history of New York.”

—Simon Baatz, New York Times bestselling author of For the Thrill of It and The Girl on the Velvet Swing

“Through a wealth of harrowing anecdotes and fascinating case-studies, Damnation Island tells the real story of how America has treated its poor, its tired, and its huddled masses: with petty cruelty, often in the name of Christian charity. A gripping and compelling read.”

—Mikita Brottman, author of The Maximum Security Book Club

“Riveting. Horn brings alive this forgotten history, and her extraordinary book has far-reaching significance not only for the past but for the future.”

—Jan Jarboe Russell, best-selling author of The Train to Crystal City

“At Blackwell’s, the inmates really were running the asylum. An important piece of history in public medicine, Damnation Island weaves a compelling narrative with threads of thorough research and realism.”

—Julie Holland, M.D., author of Weekends at Bellevue

“A riveting, character-driven dive into 19th-century New York and the extraordinary history of Blackwell’s Island. Stacy Horn has an uncanny knack for making history come alive.”

—Laurie Gwen Shapiro, author of The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica

“Blackwell’s Island’s descent into darkness is chronicled with clarity and conscience by master-story-teller Stacy Horn. No one who has taken that journey with her will return the same.”

—Teresa Carpenter, Pulitzer Prize-winner and editor of New York Diaries: 1609 to 2009

“New York’s Victorian-era reformers had an idea: to isolate the city’s indigent, diseased, mentally ill, and delinquent on an island in the East River, where they could be cared for with competence and compassion. Unfortunately, it didn’t turn out that way. Stacy Horn is the perfect Virgil for this chilling, vivid, and enthralling journey through the Inferno that was 19th-century Blackwell’s Island.”

—Gary Krist, author of Empire of Sin

“Revelatory. What occurred during the 19th and early 20th centuries in the prisons, hospitals, and insane asylum on the New York City spit of land that is now home to the fashionable Roosevelt Island constitutes the stuff of nightmares.”

—Steve Weinberg, author of Taking on the Trust: The Epic Battle of Ida Tarbell and John D. Rockefeller

“More than a diligent expose, Damnation Island presents a cautionary tale for what could happen even now, informing and educating in a way that urges us toward humbling self-reflection.”

—Katherine Ramsland, author of Confession of a Serial Killer

“Blackwell’s Island and its troubled history haunt New York City. Who better to delve into its many-layered secrets than one of America’s foremost storytellers, Stacy Horn.”

—Philip Dray, author ofAt the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America

- On Sale

- May 15, 2018

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781616208288

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use