Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

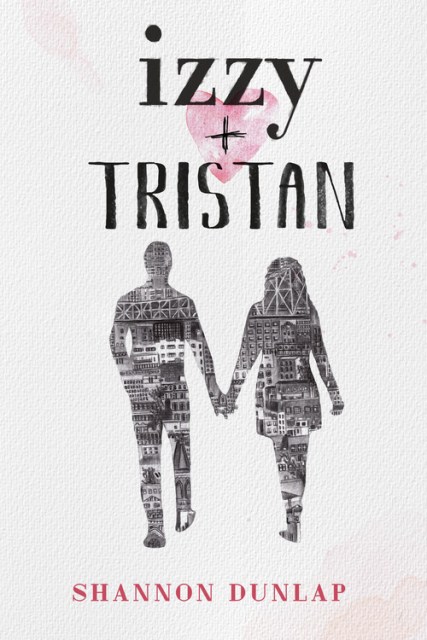

Izzy + Tristan

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$10.99Price

$14.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $10.99 $14.99 CAD

- ebook $2.99 $2.99 CAD

- Hardcover $17.99 $23.49 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 13, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A classic romantic tale with a modern twist, this dazzling Indies Introduce pick follows two teenagers as they secretly fall in love for the first time.

Izzy, a practical-minded teen who intends to become a doctor, isn’t happy about her recent move from the Lower East Side across the river to Brooklyn. She feels distanced from her family, especially her increasingly incomprehensible twin brother, as well as her new neighborhood.

And then she meets Tristan.

Tristan is a chess prodigy who lives with his aunt and looks up to his cousin, Marcus, who has watched out for him over the years. When he and Izzy meet one fateful night, together they tumble into a story as old and unstoppable as love itself.

In debut author Shannon Dunlap’s capable hands, the romance that has enthralled for 800 years is spun new. Told from several points of view, Izzy + Tristan is a love story for the ages and a love story for this very moment. This fast-paced novel is at once a gripping tale of first love and a sprawling epic about the bonds that tie us together and pull us apart and the different cultures and tensions that fill the contemporary American landscape.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 13, 2021

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Poppy

- ISBN-13

- 9780316415415

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use