Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

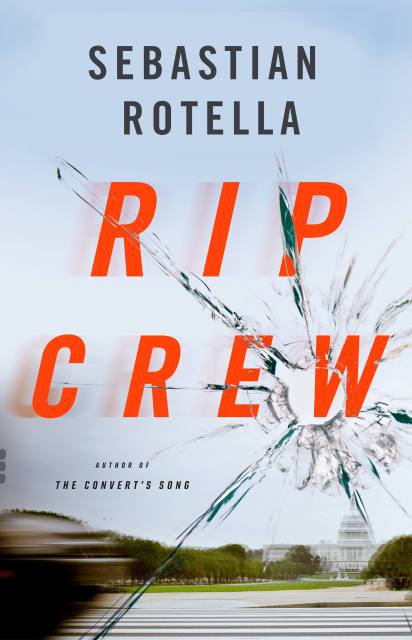

Rip Crew

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 13, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In this “taut, tense international thriller” (Alafair Burke), streetwise U.S. agent Valentine Pescatore investigates a brutal killing that reveals a vast conspiracy of wealth and power. One of Kirkus Reviews‘s Best Mysteries of the Year!

Valentine Pescatore, the globetrotting former Border Patrol agent, finds himself back on American soil investigating the merciless killing of a group of women in a motel room. At first, the crime seems to be a straightforward case of gangsters battling for territory. Soon, however, the motive is revealed to be much deeper and more sinister: a single witness who knows too much is being hunted, at any cost.

From an author who has been praised for his “pounding action scenes [and] ferocious prose style” (Marilyn Stasio, NYTBR), Rip Crew races at breakneck speed as Pescatore finds himself face-to-face with his most terrifying assignment yet.

Valentine Pescatore, the globetrotting former Border Patrol agent, finds himself back on American soil investigating the merciless killing of a group of women in a motel room. At first, the crime seems to be a straightforward case of gangsters battling for territory. Soon, however, the motive is revealed to be much deeper and more sinister: a single witness who knows too much is being hunted, at any cost.

From an author who has been praised for his “pounding action scenes [and] ferocious prose style” (Marilyn Stasio, NYTBR), Rip Crew races at breakneck speed as Pescatore finds himself face-to-face with his most terrifying assignment yet.

Genre:

-

"Rip Crew is a taut, tense international thriller, filled with complex characters and gritty dialogue. Utterly riveting."Alafair Burke, New York Times bestselling author of The Wife

-

"This latest installment in a series including Triple Crossing and The Convert's Song is about as tightly woven and rock-solid as international thrillers get. Rotella is as good at setting up action scenes as he is at springing them (which is saying something: the shootouts are terrific). The crisp dialogue feeds the sculpted plot and vice versa. There is nary a wasted moment in the book or one in which Rotella isn't in complete command. . . . Rotella's latest is a tense, gritty thriller-perfectly seedy when it needs to be and near-perfect in its overall execution."Kirkus Reviews (starred)

-

"Gritty dialog rings convincingly with authenticity as Rotella playfully inspects multiple layers of meaning inherent in dialects, news stories, and eyewitness accounts. For fans of tough crime fiction in the tradition of T. Jefferson Parker."Library Journal (starred)

-

"What a setup! It's heartrending, violent, and intriguing...readers will hang on for the revelation and the mighty clash at the end."Don Crinklaw, Booklist

-

"Rotella writes convincingly about the realities and mechanics of investigative journalism, and his detailed action scenes add just enough mayhem to keep thriller readers on the edge of their seats."Publishers Weekly

-

"Gritty dialog rings convincingly with authenticity as Rotella playfully inspects multiple layers of meaning inherent in dialects, news stories, and eyewitness accounts. For fans of tough crime fiction in the tradition of T. Jefferson Parker."Library Journal

- On Sale

- Mar 13, 2018

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316505505

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use