By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

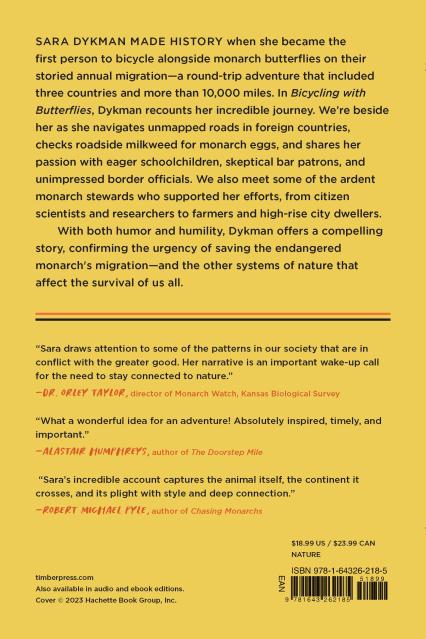

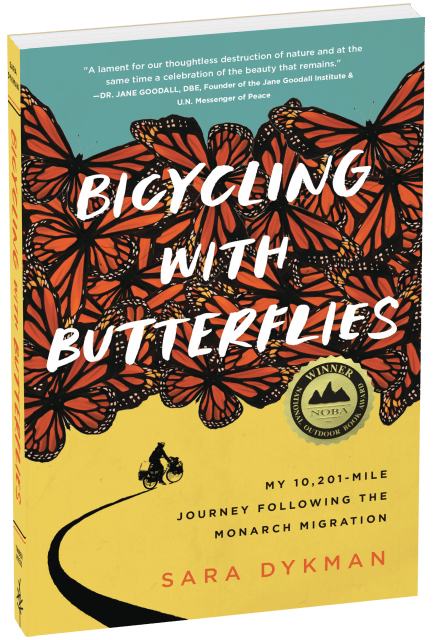

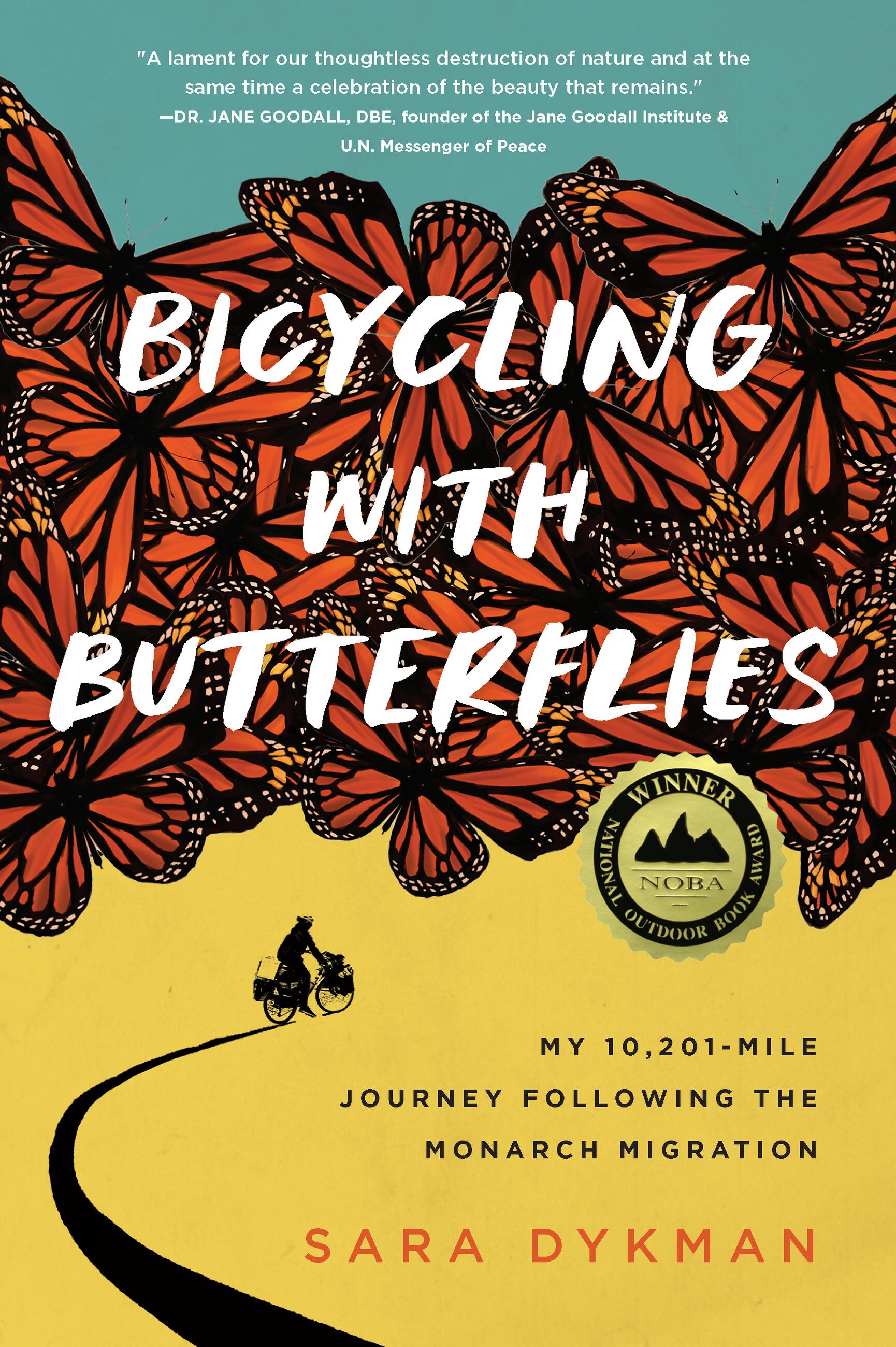

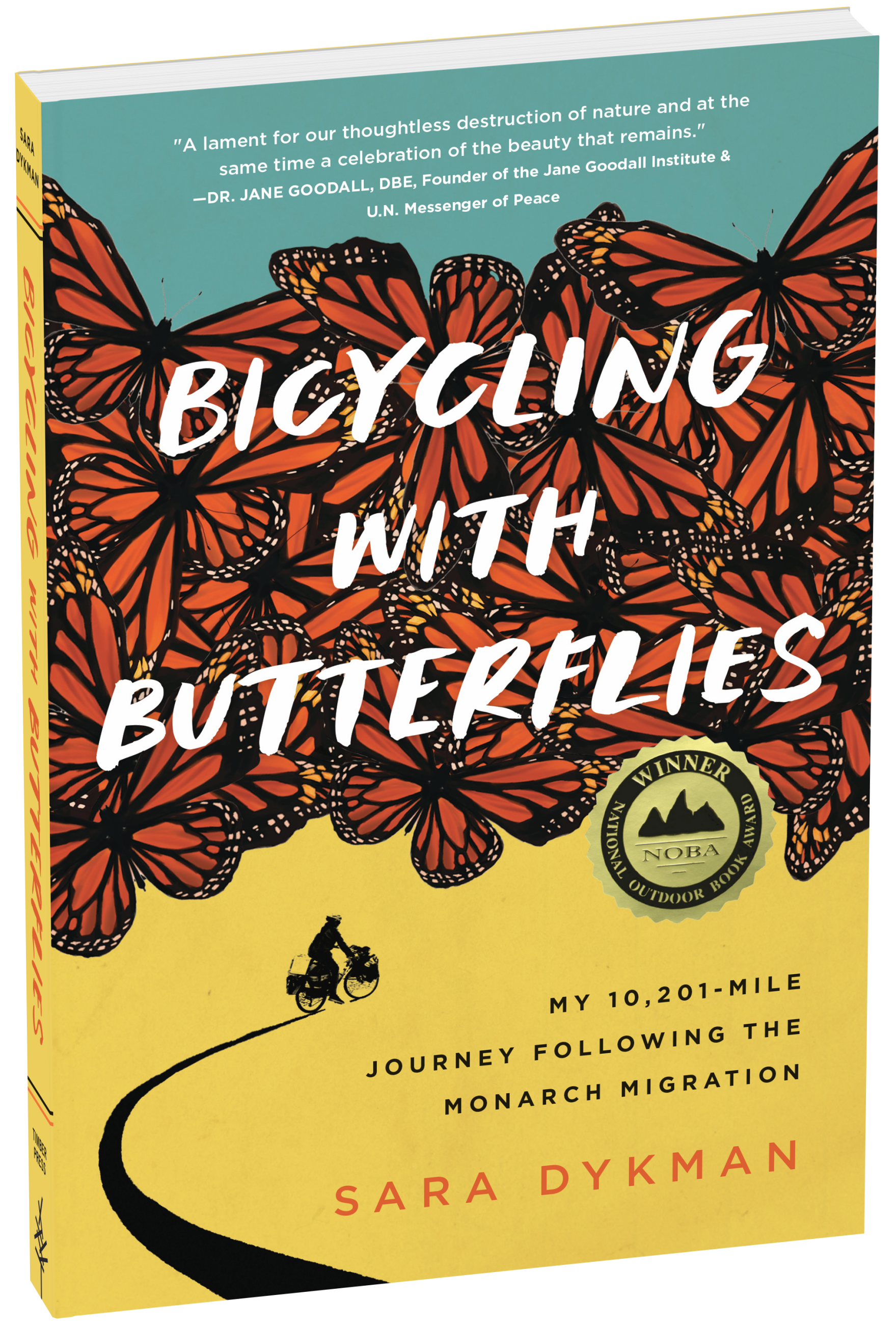

Bicycling with Butterflies

My 10,201-Mile Journey Following the Monarch Migration

Contributors

By Sara Dykman

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 14, 2023

- Page Count

- 280 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781643262185

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.95

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 14, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Science, nature, and adventure come together in this riveting account of a solo bike trip along the migratory path of the monarch butterfly.

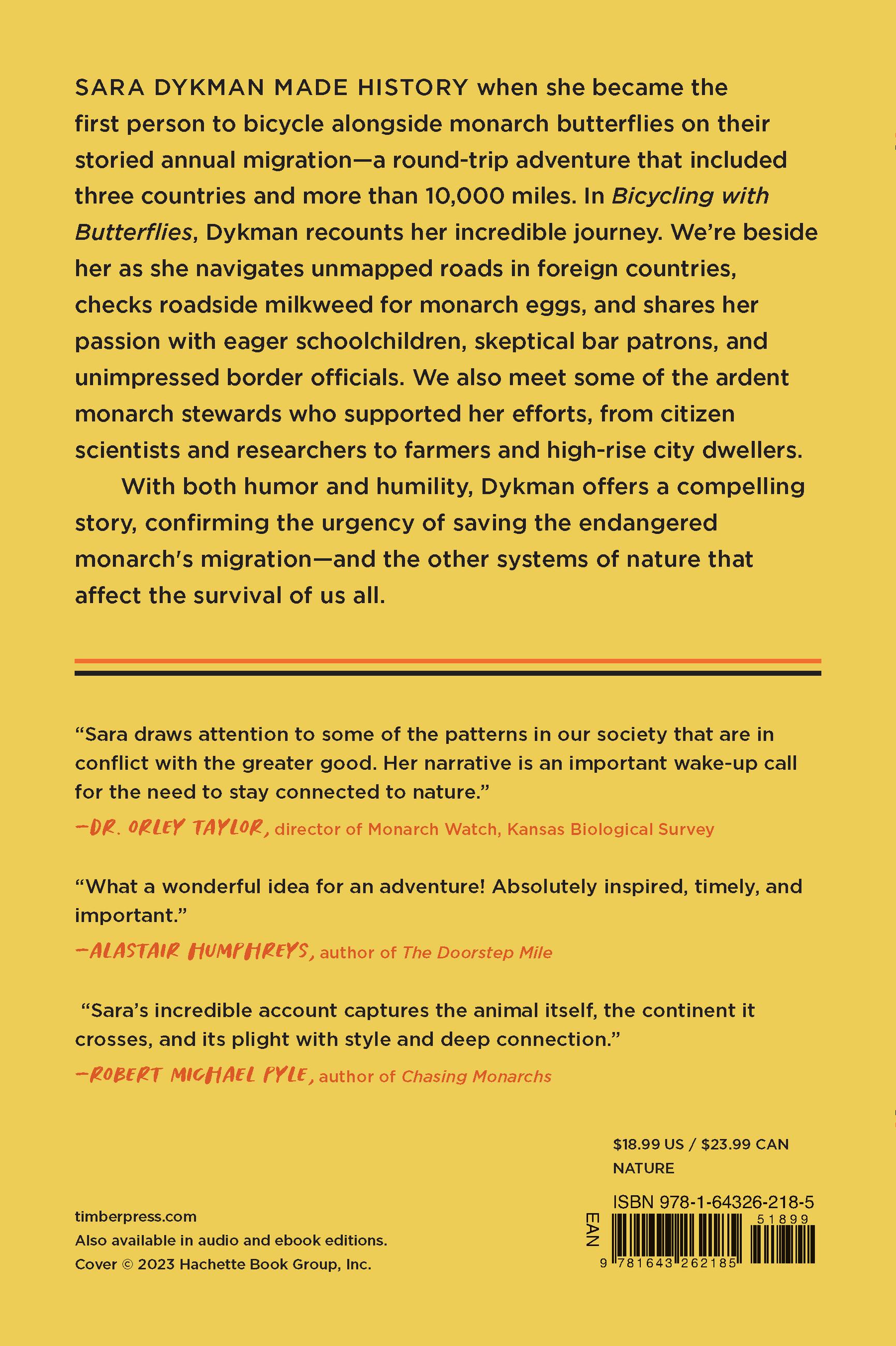

Sara Dykman made history when she became the first person to bicycle alongside monarch butterflies on their storied annual migration—a round-trip adventure that included three countries and more than 10,000 miles. Equally remarkable, she did it solo, on a bike cobbled together from used parts.

In Bicycling with Butterflies—praised as “poetic” (Publishers Weekly) and called “a collective cry for climate action” (Booklist)—Dykman recounts her incredible journey. We’re beside her as she navigates unmapped roads in foreign countries, checks roadside milkweed for monarch eggs, and shares her passion with eager schoolchildren, skeptical bar patrons, and unimpressed border officials. We also meet some of the ardent monarch stewards who supported her efforts, from citizen scientists and researchers to farmers and high-rise city dwellers.

With both humor and humility, Dykman offers a compelling story, confirming the urgency of saving the threatened monarch migration—and the other threatened systems of nature that affect the survival of us all.

-

"An extraordinary story in which Dykman seamlessly weaves together science, a real love of nature and the adventure and hazards of biking with butterflies from Mexico to Canada and back. They share an epic journey and encounter hardships, but they do not give up. The book is a lament for our thoughtless destruction of nature and at the same time a celebration of the beauty that remains. The migration of the monarch butterflies is one of the wonders of the world—we must save it for future generations." —Dr. Jane Goodall, DBE, Founder of the Jane Goodall Institute U.N. Messenger of PeaceThe Reporter

"On this improbably adventure, Sara Dykman followed the extraordinary monarch migration by bicycle, and came back to write about it. She has recorded it well. Her almost incredible account captures the animal itself, the continent it crosses, and its plight with style and deep connection." —Robert Michael Pyle, author of Chasing Monarchs and founder of the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation

“What a wonderful idea for an adventure! Absolutely inspired, timely, and important.” —Alistair Humphreys, National Geographic Adventurer of the Year and author of The Doorstep Mile and Around the World by Bike

“Told with a writer’s eye for detail and a biologist’s sensitivity to the fragile nature of the systems that support wildlife and humans . . . a keen observer of the human condition, Sara draws attention to some of the patterns in our society that are in conflict with the greater good. Her narrative is an important wake-up call for the need to stay connected to nature.” —Dr. Orley Taylor, director of Monarch Watch, Kansas Biological Survey

“People have long been fascinated by the monarch butterfly’s migration across the North American continent. Thanks to this book, readers have a better idea of what that incredible journey entails… Dykman’s enthusiasm will motivate others to be more thoughtful about their decisions.” —Library Journal

“The book is just as much a poetic travelogue as it is informative about monarch butterflies. Dykman’s research keenly supplements her experiences on the road…it may be one singular bicyclist’s word, but represents a collective cry for climate action.”—Booklist

“Dykman’s transformation as she follows the kaleidoscope of butterflies is a wonder to observe as it unfolds… Her writing is frank, uplifting, informative, and gorgeous.” —Alphabet Soup

“Dykman deftly interweaves science with adventure…I can’t recommend this book enough.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use