Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

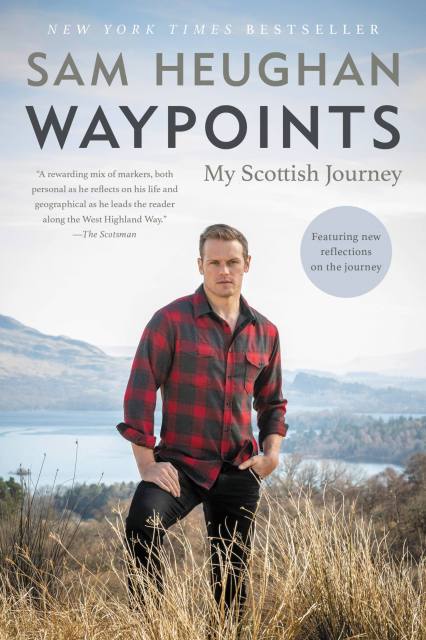

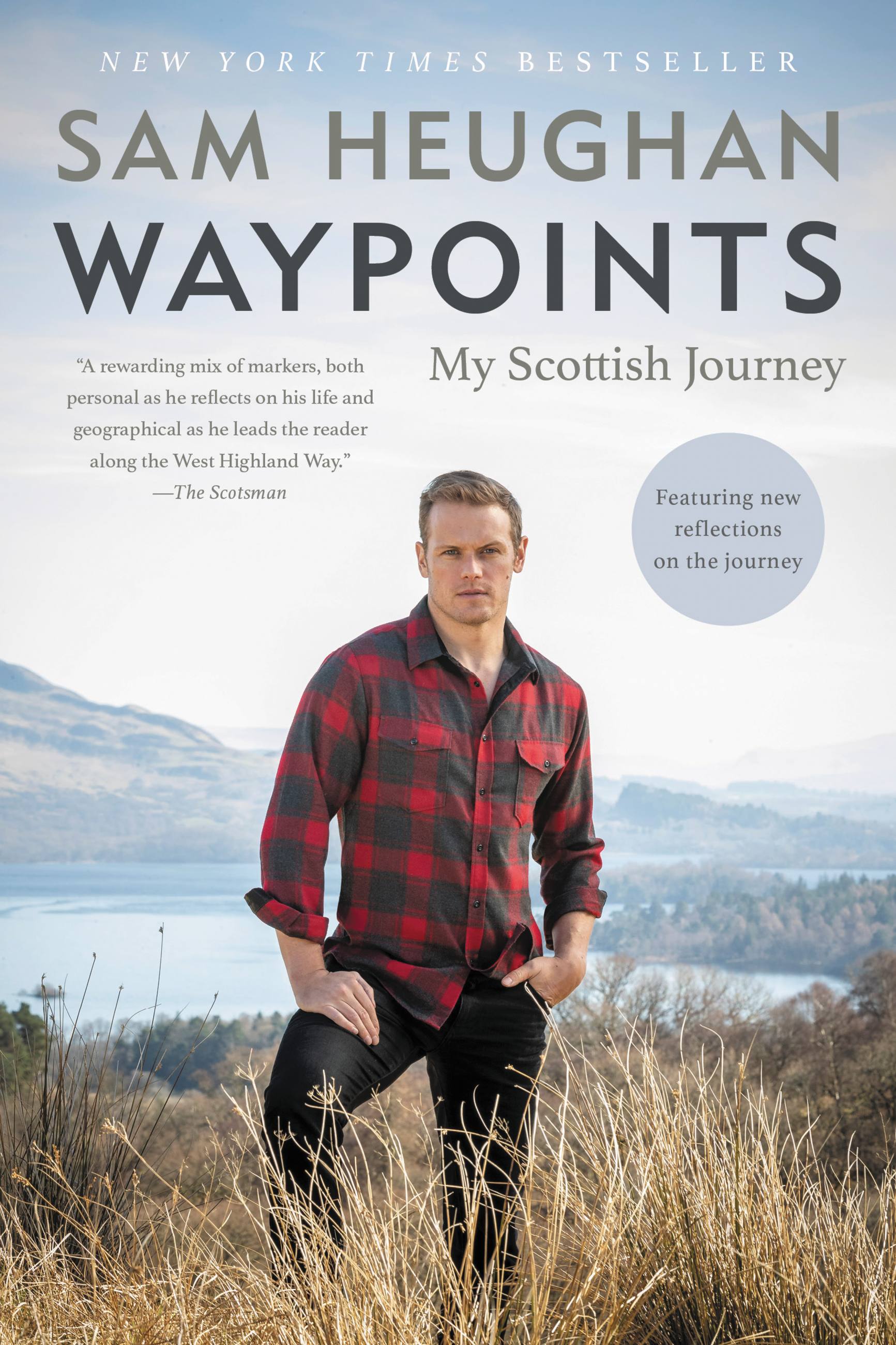

Waypoints

My Scottish Journey

Contributors

By Sam Heughan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 26, 2023

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Voracious

- ISBN-13

- 9780316495639

Price

$18.99Price

$23.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $23.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 26, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“I had to believe, because frankly, I had come so far there could be no turning back.”

In this intimate journey of self-discovery, Sam sets out along Scotland’s rugged ninety-six-mile West Highland Way to map out the moments that shaped his views on dreams and ambition, family, friendship, love, and life. The result is a love letter to the wild landscape that means so much to him, full of charming, funny, wise, and searching insights into the world through his eyes.

Waypoints is a deeply personal journey that reveals as much about Sam to himself as it does to his readers.

-

"A pleasure for fans of the author, whisky, and Scotland."Kirkus

-

“As the title suggests, Waypoints is a rewarding mix of markers, both personal as he reflects on his life and geographical as he leads the reader along the West Highland Way.”The Scotsman

-

“A deeply personal and warmly entertaining memoir that fans of Sam - and Scotland - will have a joyful time devouring.”Heat

-

“From both his walk and his career, the common lesson is the power of persistence.”The Times (London)

-

"Spirited and heartwarming"booktrib.com

-

"With disarming asides and humorous accents, Heughan's narration reveals the fun-loving yet thoughtful man behind his acting roles…Bookended by scenes with Heughan’s estranged father, Waypoints is a companionable and inspiring memoir that encourages soul-searching and mindfulness.”Bookpage