By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

The End of the Cold War: 1985-1991

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 14, 2017

- Page Count

- 688 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610397711

Price

$25.99Format

Format:

- Trade Paperback $25.99

- ebook $13.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 14, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

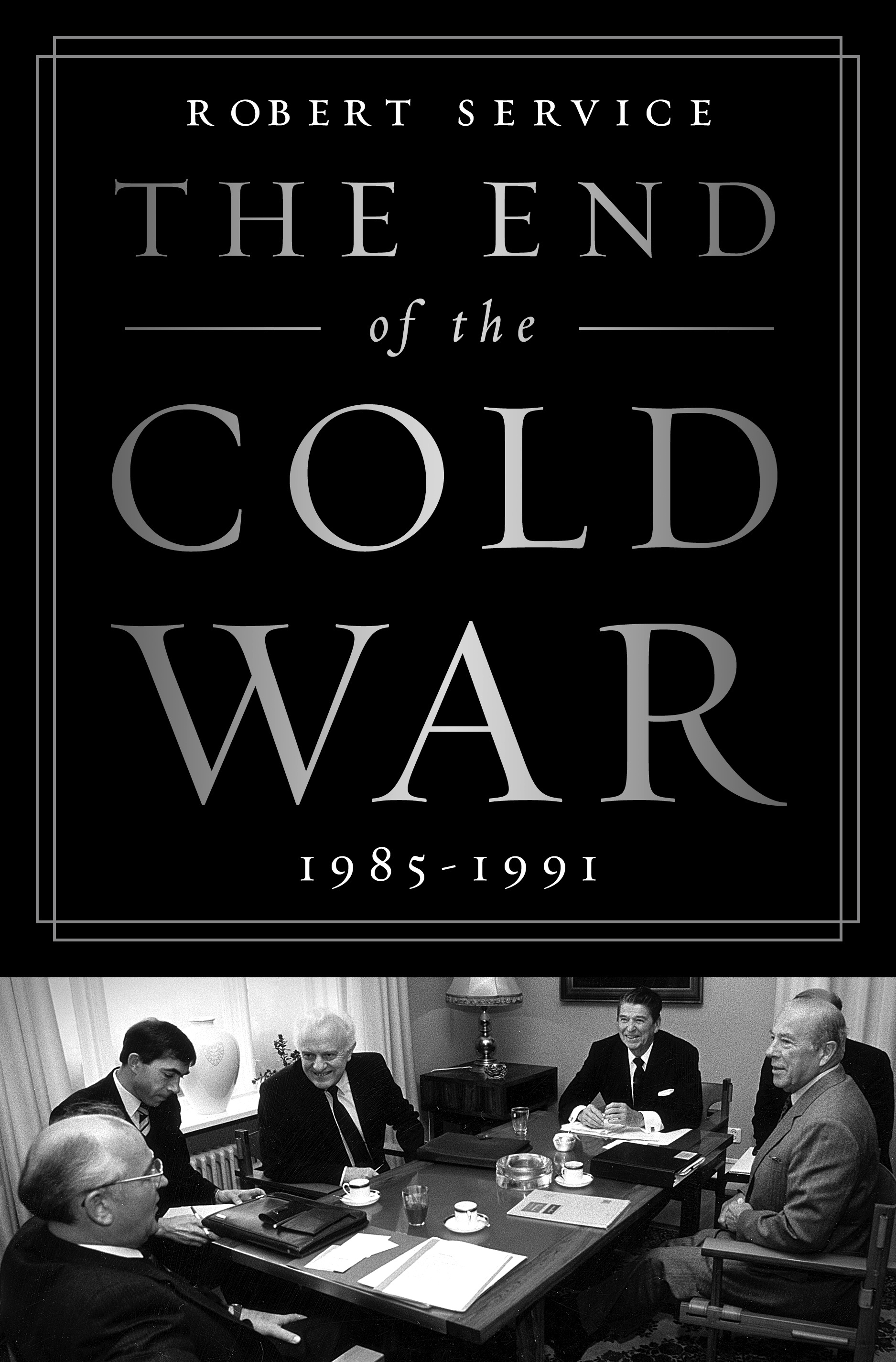

Drawing on pioneering archival research, Robert Service’s gripping investigation of the final years of the Cold War pinpoints the extraordinary relationships between Ronald Reagan, Gorbachev, George Shultz, and Shevardnadze, who found ways to cooperate during times of exceptional change around the world. A story of American pressure and Soviet long-term decline and overstretch, The End of the Cold War: 1985-1991 shows how a small but skillful group of statesmen grew determined to end the Cold War on their watch and transformed the global political landscape irreversibly.

-

“Service takes the vast literature on the Cold War's end, adds newly available archival sources, and pulls it all together into a single massive history of how ‘Washington and Moscow achieved their improbable peace.' … To cover as many elements as Service does requires very tight writing, even in a big book such as this one: as a result, he settles for sentences rather than paragraphs to cover the necessary ground.” —Foreign Affairs

“The great nonfiction book of the year… As a serious and fascinating dive into the events that shaped our world it cannot be bettered.” —Justin Webb, The Times [UK]

“Authoritative and scholarly… The End of the Cold War gets all the big questions right. The world was fortunate to have leaders who brought a half-century nightmare to a peaceful conclusion, and his readers will be grateful for Robert Service's clear explanation of how and why it happened.” —Claremont Review of Books

“[Robert] Service's book is a great investigative achievement…[he] has given us an account, unsurpassable in its detail…” —Bookforum

“A riveting read.” —The Telegraph (UK) -

A Times [UK] Book of the Year 2015

“The denouement is well known and well told in pointillist detail… [an] admirably even-handed account, which offers a compendium of the expired secrets of the White House and Kremlin.” —Wall Street Journal

"The End of the Cold War [is] a massive new study of the last days of the Soviet empire… British historian Robert Service examines newly released Politburo minutes, recently available unpublished diaries, and minutely detailed negotiation records.” —Boston Globe

"The End of the Cold War, 1985-1991 [is] a detailed, authoritative, and illuminating account of the end of the competition that defined world politics for more than four decades.” —Christian Science Monitor

“The End of the Cold War: 1985-1991 serves as a reminder that the hawks' memory of Reagan's Soviet diplomacy is selective and, ultimately, just plain inaccurate…Service succeed[s] in giving the reader a comprehensive account of the meetings and debates in the years leading up to the Soviet collapse.” —Washington Post

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use