By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

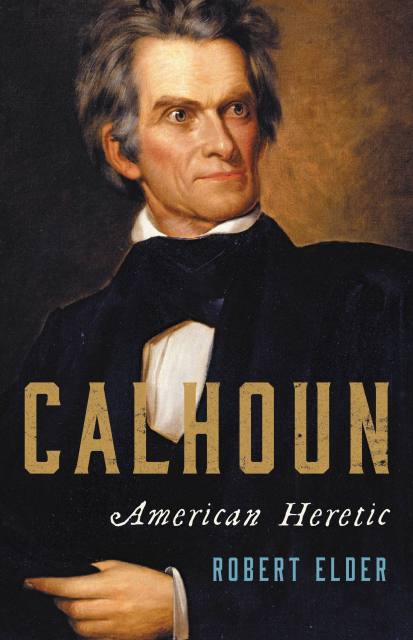

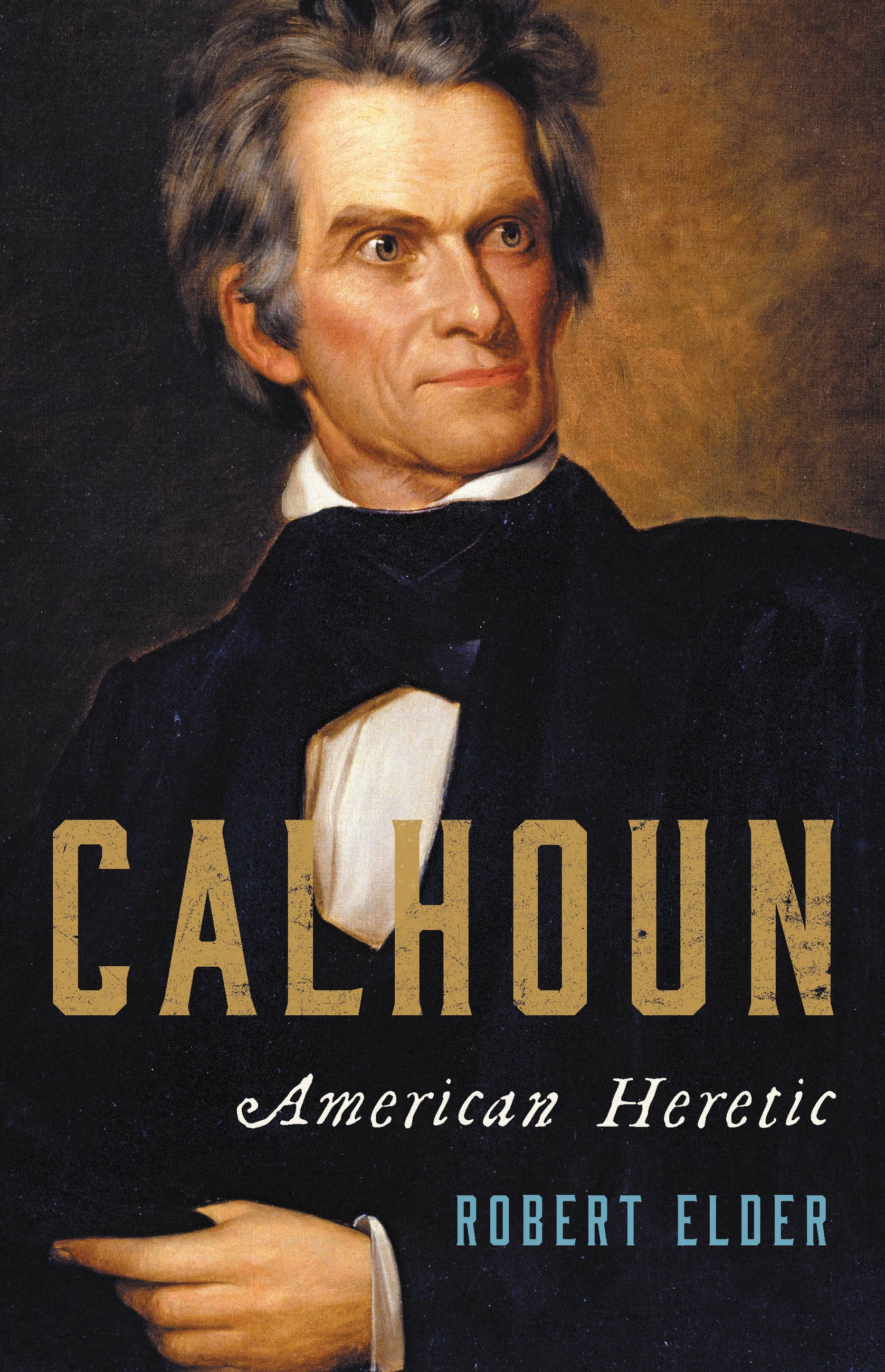

Calhoun

American Heretic

Contributors

By Robert Elder

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 16, 2021

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465096459

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $44.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 16, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A new biography of the intellectual father of Southern secession—the man who set the scene for the Civil War, and whose political legacy still shapes America today.

John C. Calhoun is among the most notorious and enigmatic figures in American political history. First elected to Congress in 1810, Calhoun went on to serve as secretary of war and vice president. But he is perhaps most known for arguing in favor of slavery as a "positive good" and for his famous doctrine of "state interposition," which laid the groundwork for the South to secede from the Union—and arguably set the nation on course for civil war.

Calhoun has catapulted back into the public eye in recent years, as some observers connected the strain of radical politics he developed to the tactics and extremism of the modern Far Right, and as protests over racial injustice have focused on his legacy. In this revelatory biographical study, historian Robert Elder shows that Calhoun is even more broadly significant than these events suggest, and that his story is crucial for understanding the political climate in which we find ourselves today. By excising Calhoun from the mainstream of American history, he argues, we have been left with a distorted understanding of our past and no way to explain our present.

John C. Calhoun is among the most notorious and enigmatic figures in American political history. First elected to Congress in 1810, Calhoun went on to serve as secretary of war and vice president. But he is perhaps most known for arguing in favor of slavery as a "positive good" and for his famous doctrine of "state interposition," which laid the groundwork for the South to secede from the Union—and arguably set the nation on course for civil war.

Calhoun has catapulted back into the public eye in recent years, as some observers connected the strain of radical politics he developed to the tactics and extremism of the modern Far Right, and as protests over racial injustice have focused on his legacy. In this revelatory biographical study, historian Robert Elder shows that Calhoun is even more broadly significant than these events suggest, and that his story is crucial for understanding the political climate in which we find ourselves today. By excising Calhoun from the mainstream of American history, he argues, we have been left with a distorted understanding of our past and no way to explain our present.

-

“An illuminating account of the life of the notorious white supremacist as well as his complex afterlife in American political culture….In his lucid book about this complex and contradictory figure, Robert Elder wisely refrains from assigning Calhoun to a stationary spot along the political spectrum….[A] valuable book.”New York Times Book Review

-

“A timely and thought-provoking biography of the South Carolina statesman whose doctrines and debates set the stage for the Civil War. In the course of his chronicle, Mr. Elder traces how Calhoun’s thinking continues to influence American society today....[A] much-needed biography.”Wall Street Journal

-

“There are some biographies which are almost impossible to write….John Caldwell Calhoun is one of those difficult subjects, something which the Baylor University historian Robert Elder acknowledges in the title of his new Calhoun biography….Still, Elder has the decency of compassion and never underestimates or burlesques Calhoun.”The New Criterion

-

"Historian Elder reassesses the life and legacy of U.S. vice president and South Carolina senator John C. Calhoun (1782–1850) in this comprehensive biography. Elder skillfully tracks Calhoun’s unusual political career trajectory, from his advocacy for war with England as a freshman congressman in 1811, to his modernization of the U.S. Army as secretary of war, resignation as Andrew Jackson’s vice president and return to Congress in 1832 as a strident advocate for states’ rights, and calls for a constitutional amendment protecting slavery in the weeks before his death in 1850.... Elder is a graceful writer who persuasively argues that the beliefs and policies Calhoun amplified continue to shape American politics."Publishers Weekly

-

"A forcefully argued case for placing Calhoun at the center of any honest account of America's tangled past."Kirkus

-

“This well-researched book offers a definitive account of Calhoun.”Library Journal

-

"In this much-needed new biography, Robert Elder cuts through two hundred years of interpretive tangle to reveal Calhoun as he was and as he remains with us today—perhaps the most creative and darkly influential reactionary America has ever produced."Matthew Karp, author of This Vast Southern Empire

-

"Because he was slavery's most eloquent defender as well as a founding father of the Confederacy, it's been difficult for scholars to come to terms with John C. Calhoun’s foundational role in America's political and social development. This engrossing biography reveals how the United States and one of its most prominent intellectuals grew in tandem during the first half of the nineteenth century. As much as we might like to forget Calhoun, Elder reveals just how short the path from his America to our own actually is."Amy S. Greenberg, author of A Wicked War

-

"Robert Elder has written a brilliant reinterpretation of one of the most vital personalities in American history. Beautifully written, well argued, and carefully researched, Elder’s book offers an unflinching view of Calhoun's virtues and flaws and breaks new ground in revealing his significance as one of the first modern theorists of secession in the age of the nation-state. This is an ideal book to prompt conversations about our country’s difficult history."Orville Vernon Burton, author of The Age of Lincoln

-

"Through careful attention both to Calhoun's rhetoric and that of his political opponents, and to the global context for American debates, Elder sheds light on Calhoun's broad influence and enduring, tragic legacy. To understand the depth of American racism and the shape of Americans' ongoing contests over the scope of federal power, Elder argues, one must grapple with Calhoun's relentless campaign to impose his political will on South—to make his heresies into the region's orthodoxies. This book is a bracing reminder of how the genre of biography can explicate the history of ideas."Elizabeth R. Varon, author of Armies of Deliverance