Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

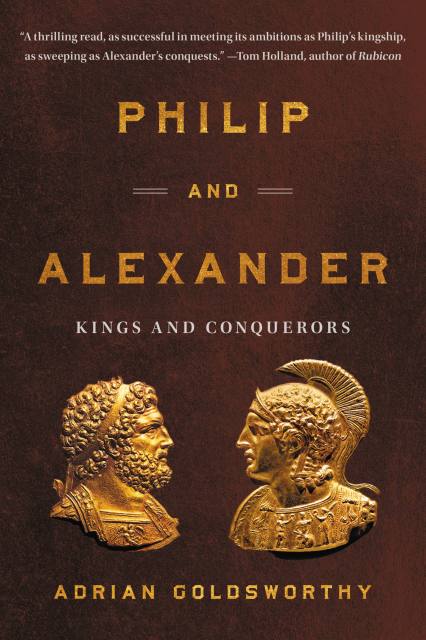

Philip and Alexander

Kings and Conquerors

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 18, 2022

- Page Count

- 624 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781541602625

Price

$22.99Price

$29.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $22.99 $29.99 CAD

- Digital download $15.99 $20.99 CAD

- Hardcover $35.00 $44.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 18, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Brings to life the full drama of ancient history.” —Wall Street Journal

Alexander the Great’s conquests staggered the world. He led his army across thousands of miles, overthrowing the greatest empires of his time and building a new one in their place. He claimed to be the son of a god, but he was actually the son of Philip II of Macedon.

Philip inherited a minor kingdom that was on the verge of dismemberment, but despite his youth and inexperience, he made Macedonia dominant throughout Greece. It was Philip who created the armies that Alexander led into war against Persia.

In Philip and Alexander, classical historian Adrian Goldsworthy shows that without the work and influence of his father, Alexander could not have achieved so much. This is the groundbreaking biography of two men who together conquered the world.

-

“A compelling but temperate book, giving readers an in-depth but dispassionate account of its subjects….Mr. Goldsworthy has a rare gift for imagining and describing ancient warfare….He combines the talents of scholar and storyteller, bringing to life the full drama of ancient history while assessing the evidence with a critical eye.”Wall Street Journal

-

“[Goldsworthy] brings a careful, often insightful balance to the familiar stories.”Open Letters Review

-

“Contributes significantly to making these scholarly developments accessible to a very wide audience, through engaging narratives which capture the political complexity of the Greek world both before and after Alexander. The major innovation of Goldsworthy's vivid Philip and Alexander is to pair Alexander's biography with that of his father, Philip II.”Times Literary Supplement

-

“Belongs on the (sturdy) shelf of any reader interested in military, political, or social history.”Minerva Magazine

-

“By pairing the two giants of Macedonia, Goldsworthy helps the reader understand Alexander's life all the better, and sheds light on the achievements and character of Philip.”Aspects of History

-

“A gripping history that combined deep scholarship with readability ... This is an epic history. Very much in the vein of the Tom Holland histories of empire, enjoyable and informative but also gripping.”NB Magazine

-

“Riveting...Goldsworthy is the best sort of writer on ancient times. He eschews psychohistory, explains the wildly unfamiliar culture of that era, and speculates carefully...An outstandingly fresh look at well-trodden ground.”Kirkus (starred review)

-

“An impressive dual biography.... Goldsworthy expertly mines ancient sources to parse fact from legend...This is a fascinating and richly detailed look at two men who 'changed the course of history.'”Publishers Weekly

-

“Thorough and riveting.”Library Journal (starred review)

-

“Philip and Alexander is another wonderful product of Adrian Goldsworthy's historical craft -- sterling scholarship, engaging prose, insightful analysis, and unbiased assessment. Goldsworthy explores brilliantly the complex relationship between father and son, the failure of the Greek city-states to stop them, the proper credit for the Macedonian expansion, and the megalomania of Alexander's near global conquests. A brilliant account of how father and son changed the world, for both good and bad.”Victor Davis Hanson, author of A War Like No Other

-

“A thrilling read, as successful in meeting its ambitions as Philip's kingship, as sweeping as Alexander's conquests.”Tom Holland, author of Rubicon

-

“Philip and Alexander is history writing at its best. In one volume, Adrian Goldsworthy tells the story of perhaps the most successful father-son pair of conquerors of all time. He highlights both the drama of their violent achievements and the consequences that were felt for centuries. The result is expert, fluent, and vivid.”Barry Strauss, author of Ten Caesars