Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

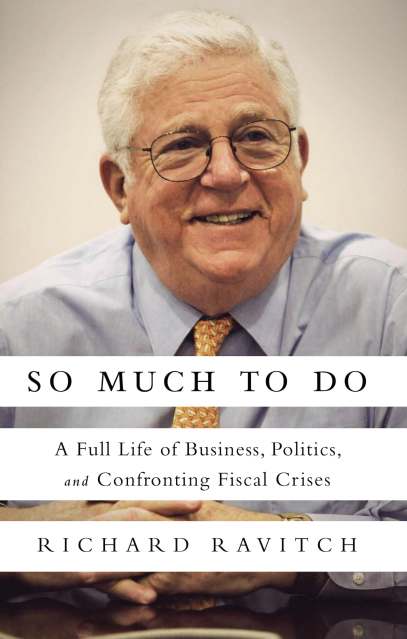

So Much to Do

A Full Life of Business, Politics, and Confronting Fiscal Crises

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 29, 2014

- Page Count

- 280 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610390927

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 29, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

It was no surprise that those endeavors ultimately led to a life of public service. In 1975, Ravitch was asked by then New York Governor Hugh Carey to arrange a rescue of the New York State Urban Development Corporation, a public entity that had issued bonds to finance over 30,000 affordable housing units but was on the verge of bankruptcy. That same year, Ravitch was at Carey’s side when New York City’s biggest banks said they would no longer underwrite its debt and he became instrumental to averting the city’s bankruptcy.

Throughout his career, Ravitch divided his time between public service and private enterprise. He was chairman of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority from 1979 to 1983 and is generally credited with rebuilding the system. He turned around the Bowery Savings Bank, chaired a commission that rewrote the Charter of the City of New York, served on two Presidential Commissions, and became chief labor negotiator for Major League Baseball.

Then, in 2008, after Governor Eliot Spitzer resigned in a prostitution scandal and New York State was in a post-financial-crisis meltdown, Spitzer’s successor, David Paterson, appointed Ravitch Lieutenant Governor and asked him to make recommendations regarding the state’s budgeting plan. What Ravitch found was the result of not just the economic downturn but years of fiscal denial. And the closer he looked, the clearer it became that the same thing was happening in most states. Budgetary pressures from Medicaid, pension promises to public employees, and deceptive budgeting and borrowing practices are crippling our states’ ability to do what only they can do — invest in the physical and human infrastructure the country needs to thrive. Making this case is Ravitch’s current public endeavor and it deserves immediate attention from both public officials and private citizens.