By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

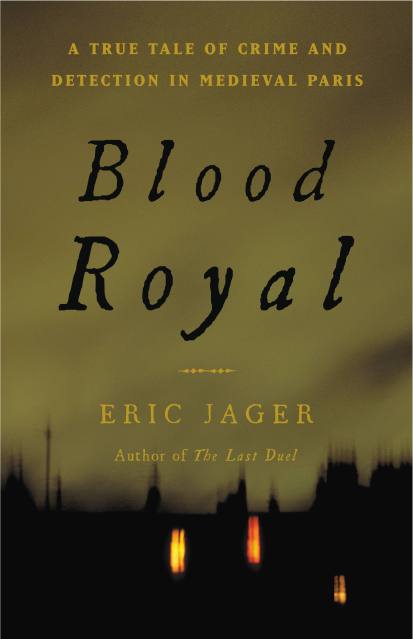

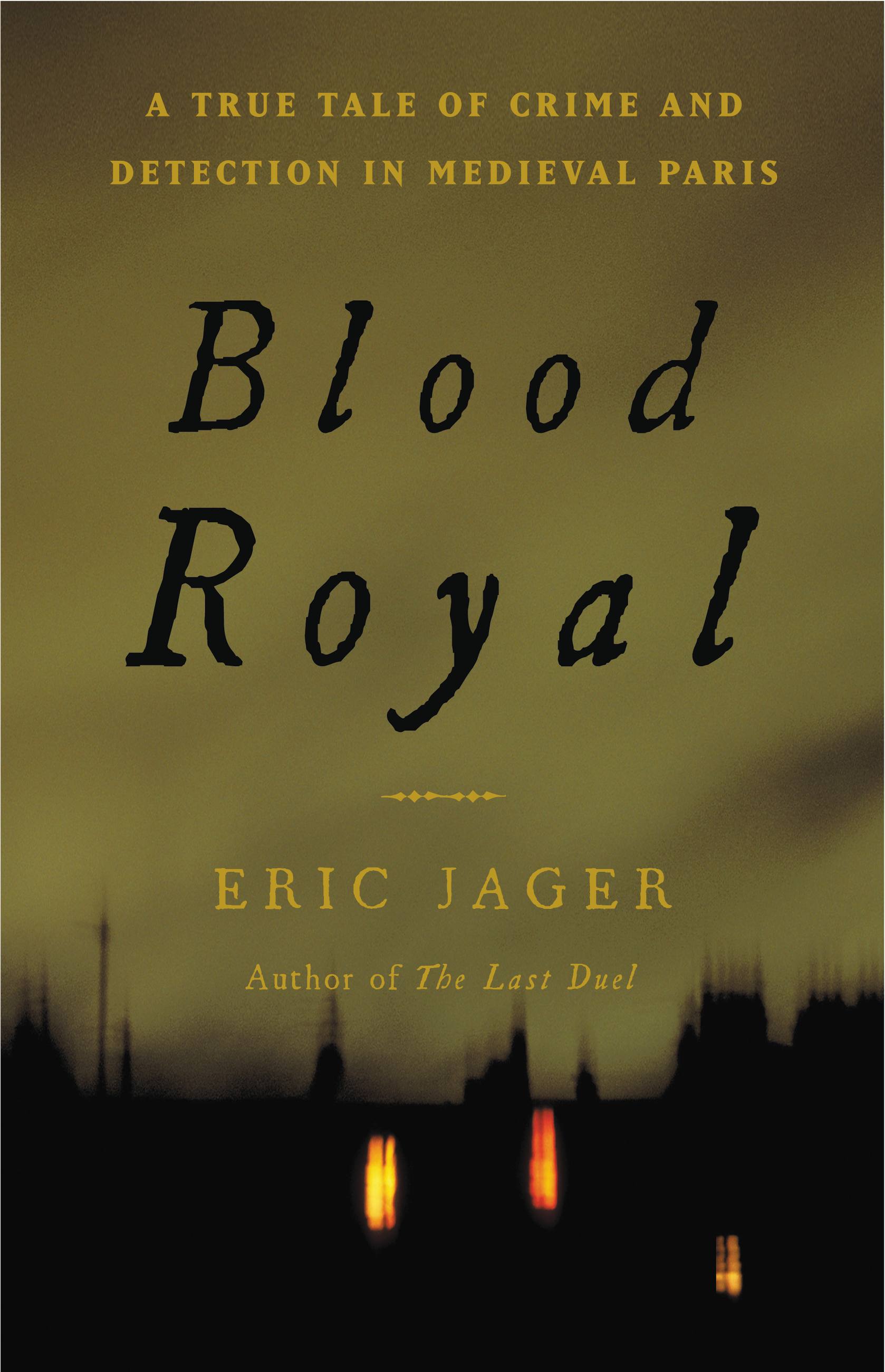

Blood Royal

A True Tale of Crime and Detection in Medieval Paris

Contributors

Read by Rene Auberjonois

By Eric Jager

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 25, 2014

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781478951742

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Hardcover $39.00 $49.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 25, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A riveting true story of murder and detection in 15th-century Paris, by one of the most brilliant medievalists of his generation.

On a chilly November night in 1407, Louis of Orleans was murdered by a band of masked men. The crime stunned and paralyzed France since Louis had often ruled in place of his brother King Charles, who had gone mad. As panic seized Paris, an investigation began. In charge was the Provost of Paris, Guillaume de Tignonville, the city’s chief law enforcement officer — and one of history’s first detectives. As de Tignonville began to investigate, he realized that his hunt for the truth was much more dangerous than he ever could have imagined.

A rich portrait of a distant world, Blood Royal is a gripping story of conspiracy, crime and an increasingly desperate hunt for the truth. And in Guillaume de Tignonville, we have an unforgettable detective for the ages, a classic gumshoe for a cobblestoned era.

On a chilly November night in 1407, Louis of Orleans was murdered by a band of masked men. The crime stunned and paralyzed France since Louis had often ruled in place of his brother King Charles, who had gone mad. As panic seized Paris, an investigation began. In charge was the Provost of Paris, Guillaume de Tignonville, the city’s chief law enforcement officer — and one of history’s first detectives. As de Tignonville began to investigate, he realized that his hunt for the truth was much more dangerous than he ever could have imagined.

A rich portrait of a distant world, Blood Royal is a gripping story of conspiracy, crime and an increasingly desperate hunt for the truth. And in Guillaume de Tignonville, we have an unforgettable detective for the ages, a classic gumshoe for a cobblestoned era.

Genre:

-

Praise for THE LAST DUEL:Kirkus Reviews

"This high-suspense, sanguinary tale ensnares readers. . . . The tension is nearly unendurable. . . . Sex, savagery, and high-level political maneuvers energize a splendid piece of popular history." -

"Jager provides an excellent depiction of feudal society, placing the reader into the lives of knights and nobles, detailing their relationships with each other and their lords. The ongoing Hundred Years' War and each man's role in it give this personal conflict its historical context. The story of the duel and the rivalry leading up to it make for quick reading as enthralling and engrossing as any about a high-profile celebrity scandal today."Gavin Quinn, Booklist

-

"If you read only one book about the Middle Ages, Eric Jager's thriller is the one to read."Steven Ozment, author of A Mighty Fortress and The Burgermeister's Daughter

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use