By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

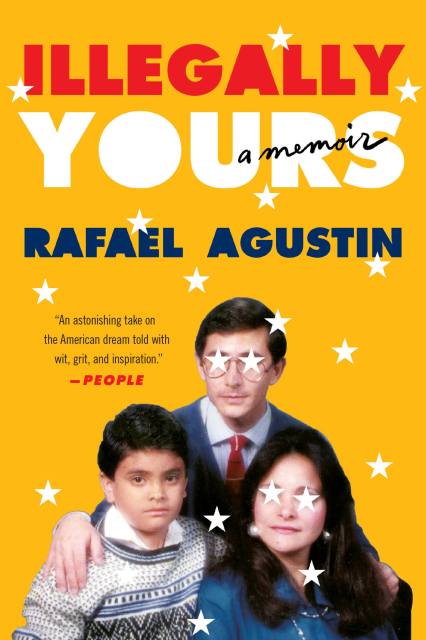

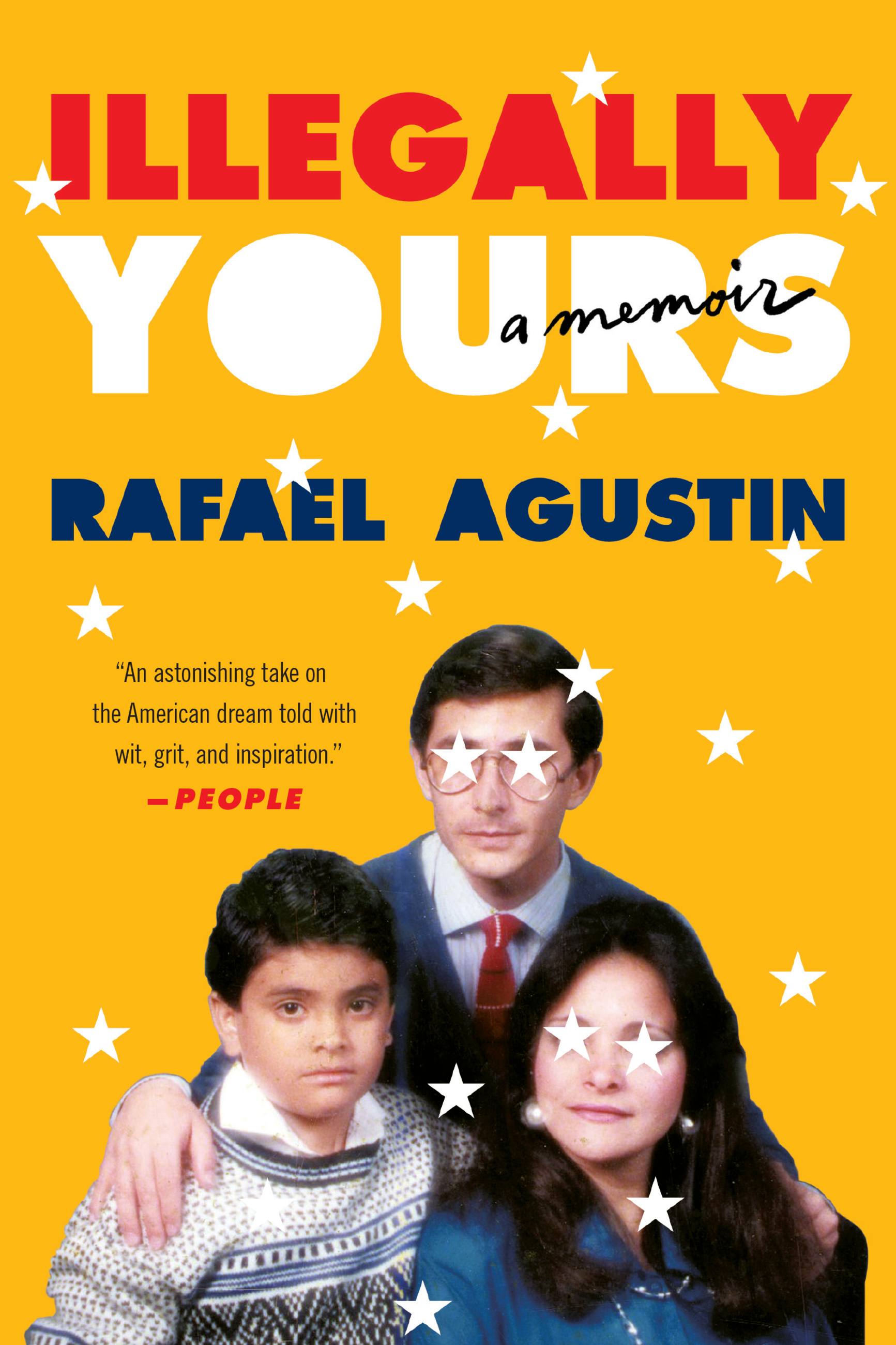

Illegally Yours

A Memoir

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 11, 2023

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538705957

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $37.00 $48.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 11, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

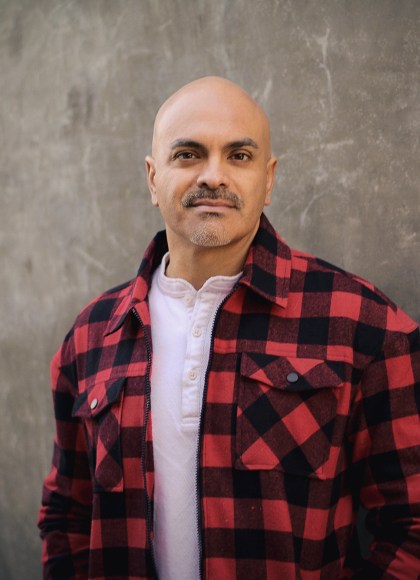

Now in paperback, a funny and poignant memoir about how as a teenager, TV writer Rafael Agustin (Jane The Virgin) accidentally discovered he was undocumented and how that revelation turned everything he thought he knew about himself and his family upside down.

Growing up, Rafa’s parents didn’t want him to feel different because, as his mom told him: “Dreams should not have borders.” But when he tried to get his driver’s license during his junior year of high school, his parents were forced to reveal his immigration status. Suddenly, the kid who modeled his entire high school career after American TV shows had no idea what to do — there was no episode of Saved by the Bell where Zack gets deported! While his parents were relieved to no longer live a lie in front of their son, Rafa found himself completely unraveling in the face of his uncertain future.

Illegally Yours is a heartwarming, comical look at how this struggling Ecuadorian immigrant family bonded together to navigate Rafa’s school life, his parents’ work lives, and their shared secret life as undocumented Americans, determined to make the best of their always turbulent and sometimes dangerous American existence. From using the Ricky Martin/Jennifer Lopez “Latin Explosion” to his social advantage in the ‘90s to how his parents—doctors in their home country of Ecuador—were reduced to working menial jobs in the US, the family’s secret became their struggle, and their struggle became their hustle. An alternatingly hilarious and touching exploration of belonging and identity, Illegally Yours revolves around one very simple question: What does it mean to be American?

Growing up, Rafa’s parents didn’t want him to feel different because, as his mom told him: “Dreams should not have borders.” But when he tried to get his driver’s license during his junior year of high school, his parents were forced to reveal his immigration status. Suddenly, the kid who modeled his entire high school career after American TV shows had no idea what to do — there was no episode of Saved by the Bell where Zack gets deported! While his parents were relieved to no longer live a lie in front of their son, Rafa found himself completely unraveling in the face of his uncertain future.

Illegally Yours is a heartwarming, comical look at how this struggling Ecuadorian immigrant family bonded together to navigate Rafa’s school life, his parents’ work lives, and their shared secret life as undocumented Americans, determined to make the best of their always turbulent and sometimes dangerous American existence. From using the Ricky Martin/Jennifer Lopez “Latin Explosion” to his social advantage in the ‘90s to how his parents—doctors in their home country of Ecuador—were reduced to working menial jobs in the US, the family’s secret became their struggle, and their struggle became their hustle. An alternatingly hilarious and touching exploration of belonging and identity, Illegally Yours revolves around one very simple question: What does it mean to be American?

-

“Agustin’s memoir cements its place in a growing collection of personal literature about the immigrant experience written in recent years.”USA Today

-

"This award-winning TV writer's immigration journey is an astonishing take on the American Dream told with wit, grit and inspiration."People Magazine

-

"[Agustin's] memoir puts a comedic and pop cultural spin on a classic American coming-of-age tale."The Hollywood Reporter

-

“Agustin offers poignant musings on the difficulties of existing in a country where the notion of race “is mostly understood as a Black and white paradigm.” What emerges is an inspiring and often hilarious story that echoes Agustin’s mother’s refrain: “Dreams should not have borders.” Funny as he is, Agustin is a serious talent.”Publishers Weekly, starred review

-

"The blissful joy of full American citizenship and a successful career form the satisfying coda to this thoughtful, inspiring memoir. An enthusiastic and motivational self-portrait."Kirkus Reviews

-

"[A] comedic and heartfelt memoir. . . Agustin writes with a deft humor that juxtaposes poignant memories with wry observations, highlighting the people who showed him kindness and helped him carve out his successful career. Under its breezy tone, this memoir is an honest exploration of the stamina and sacrifices it takes to dream in spite of the violence of borders. “Library Journal

-

"Funny is where the heart is. But this book is more than just funny––it’s candid, discerning, and truthful in the most specific and humane ways about what it means to be an immigrant, undocumented or not, in America. A writer of immense heart, Rafael Agustín pierces through these pages."Jose Antonio Vargas, founder of Define American and best-selling author of Dear America: Notes of an Undocumented Citizen

-

“I really would’ve preferred more poop jokes or a more intense exploration of the deleterious effects that the immigrant experience has on one’s bowels, but even in their absence, Illegally Yours manages to provide a bighearted and unforgettable look at the real experience of undocumented immigrants in the United States. Buy this book because he bought mine.”Eddie Huang, bestselling author of Fresh Off the Boat

-

“I love when I read someone’s story about their past, their present, and their future. In Illegally Yours, Rafael does a fantastic job of painting pictures and experiences with words. You realize that regardless of who the reader is or where they come from, they can connect with his book. It simply displays a full range of emotions from joy to struggle—exactly what life is. It does a great job of showing what one is capable of when given a fighting chance.”Cristela Alonzo, comedian, writer, and first Latina to create/write/star in a network sitcom

-

"In this poignant memoir, Rafael Agustin welcomes us into his life, his home, and his heart. Fluctuating between witty humor and tender vulnerability, he shows us how he became the amazing human being that he is today. This book is equal parts an act of rebellion and an act of celebration—rebellion against a society that thinks immigrants should keep our stories quiet instead of sharing them with the world, and a celebration of the resilience of the immigrant spirit."Reyna Grande, bestselling author of The Distance Between Us

-

“You cannot change someone’s mind before first changing their heart. Rafael Agustin's Illegally Yours does that with one of the most divisive issues in America today: immigration.”Alyssa Milano, activist, actor, producer, and bestselling author of Hope

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use