By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

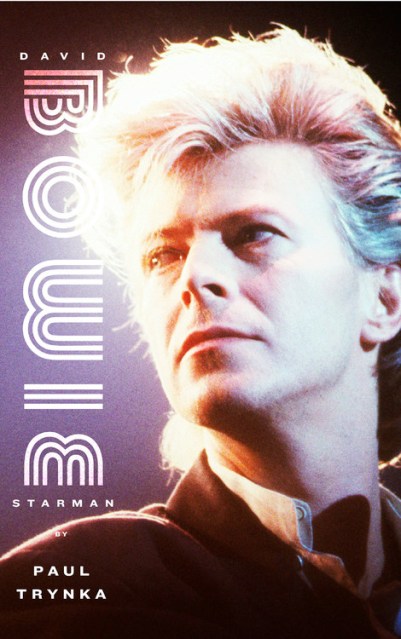

David Bowie: Starman

Contributors

By Paul Trynka

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 18, 2011

- Page Count

- 544 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316032254

Price

$47.00Price

$60.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $47.00 $60.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 18, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Ziggy Stardust,” “Changes,” Under Pressure,” “Let’s Dance,” “Fame,” “Heroes,” and of course, “Starman.” These are the classic songs of David Bowie, the artist whose personas are indelibly etched in our pop consciousness alongside his music. He wrote and recorded with everyone from Iggy Pop to Freddie Mercury to John Lennon, sold 136 million albums, has one of the truly great voices, and influenced bands as wide-ranging as Nirvana and Franz Ferdinand.

Paul Trynka illuminates Bowie’s seemingly contradictory life and his many reinventions as an artist, offering over 300 new interviews with everyone from classmates to managers to lovers. He reveals Bowie’s broad influence on the entertainment world, from movie star to modern-day icon, trend-setter to musical innovator. This book will define Bowie for years to come.

Paul Trynka illuminates Bowie’s seemingly contradictory life and his many reinventions as an artist, offering over 300 new interviews with everyone from classmates to managers to lovers. He reveals Bowie’s broad influence on the entertainment world, from movie star to modern-day icon, trend-setter to musical innovator. This book will define Bowie for years to come.

-

"British rock journalist Paul Trynka considers at length the Startling androgyny that made Bowie a defining human being of the 1970s....this book feels close to definitive....many moments in David Bowie: Starman made me lean forward with pleasure. "Dwight Garner, The New York Times

-

"British rock journalist Paul Trynka captures seemingly every glitter-god pretension and Lycra outfit, interviewing scores of friends, bandmates and detractors. The result is the most complete and compelling portrait of Bowie's life ever assembled."Andy Greene, Rolling Stone

-

With extensive research, a well judged reappraisal of the work, and an impressively nuanced approach to the drives that have motored the many lives of David Bowie, Paul Trynka has delivered a sharp, elegant and convincing volume on the man that brings freshness to a familiar story.Mark Paytress, Mojo

-

Truly definitive... Trynka's second successive exemplar of the rock biographer's art.Ian Fortnam, Classic Rock

-

Something special...The book includes interviews with those who know Bowie best, from childhood friends to those working most closely with him today....This is a terrific book, and readers will be rushing to relisten to the artist's back catalog. Not to be missed.Bill Baars, Library Journal

-

"Rich in observations from the collaborators and lovers [Bowie] burned through with roughly equal ruthlessness, the book is thorough enough to satisfy all but the most obsessive acolyte."Chris Klimek, Dallas Morning News

-

"Paul Trynka's new book, BOWIE: STARMAN, ...a deeply researched and closely observed accounting of Bowie's life and career. Sure, there's plenty of sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll anecdotes. But Trynka takes us well beyond all that rock-star stuff and digs deeply into those peculiar confluences of gifted musical personnel and roiling creative juices that have produced Bowie's oeuvre."Mark Baker, Paste

-

"Trynka hews to Bowie's own narrative...the author's musical credibility is unquestionable. For the rock fan, pop-culture junkie or curious passerby, there's plenty to be entertained by."Maureen Callahan, New York Post

-

"Drawing upon more than 250 new interviews with friends of Bowie and on previously published interviews with Bowie, former Mojo editor affectionately chronicles the life and music of Bowie from his childhood and youth to the high points of his career, his recent heart attack and almost total disappearance from the music scene...Bowie, in Trynka's hands is a man who has never settled for the predictable."Publisher's Weekly

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use