Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

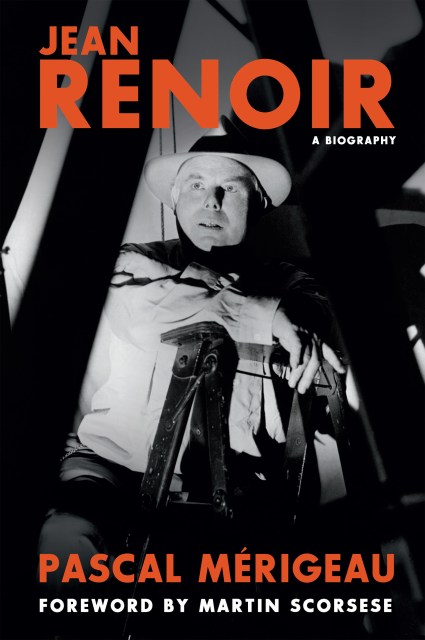

Jean Renoir: A Biography

Contributors

Foreword by Martin Scorsese

Translated by Bruce Benderson

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$18.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $18.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $41.99 $52.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 3, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

An estimated 75 percent of the book details previously unknown information about the filmmaker, including Renoir’s close affiliation with Communism in the ’30s (when he was the Party’s official director) and his work with the fascist regimes during World War II; his previously uncredited Hollywood film, The Amazing Mrs. Holiday; and new information on the making of his most famous films.

Drawing from unpublished or little known sources, this biography is a completely fresh approach to the maker of Grand Illusion and The Rules of the Game, redefining the very function of the movie director and simultaneously recounting the history of a century.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 3, 2017

- Page Count

- 1104 pages

- Publisher

- Running Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780762456086

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use