Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

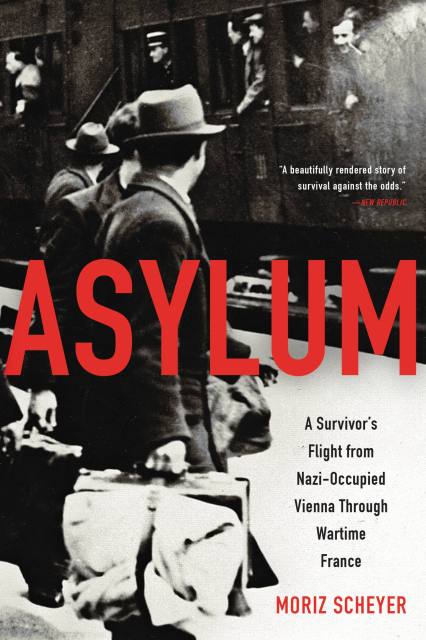

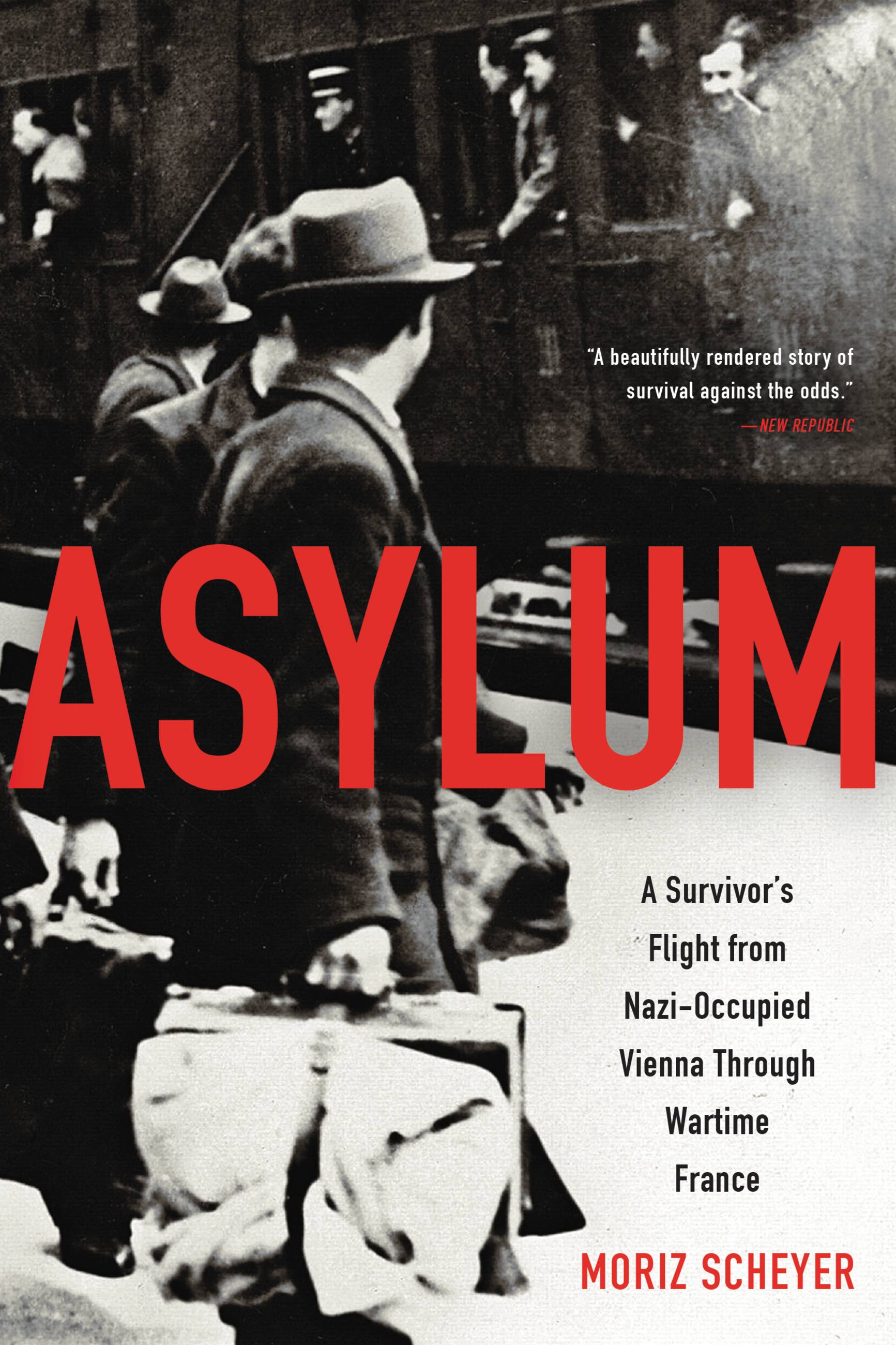

Asylum

A Survivor's Flight from Nazi-Occupied Vienna Through Wartime France

Contributors

Translated by P. N. Singer

Epilogue by P. N. Singer

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.49 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 27, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

A recently discovered account of an Austrian Jewish writer’s flight, persecution, and clandestine life in wartime France.

As arts editor for one of Vienna’s principal newspapers, Moriz Scheyer knew many of the city’s foremost artists, and was an important literary journalist. With the advent of the Nazis he was forced from both job and home. In 1943, in hiding in France, Scheyer began drafting what was to become this book.

Tracing events from the Anschluss in Vienna, through life in Paris and unoccupied France, including a period in a French concentration camp, contact with the Resistance, and clandestine life in a convent caring for mentally disabled women, he gives an extraordinarily vivid account of the events and experience of persecution.

After Scheyer’s death in 1949, his stepson, disliking the book’s anti-German rhetoric, destroyed the manuscript. Or thought he did. Recently, a carbon copy was found in the family’s attic by P.N. Singer, Scheyer’s step-grandson, who has translated and provided an epilogue.

As arts editor for one of Vienna’s principal newspapers, Moriz Scheyer knew many of the city’s foremost artists, and was an important literary journalist. With the advent of the Nazis he was forced from both job and home. In 1943, in hiding in France, Scheyer began drafting what was to become this book.

Tracing events from the Anschluss in Vienna, through life in Paris and unoccupied France, including a period in a French concentration camp, contact with the Resistance, and clandestine life in a convent caring for mentally disabled women, he gives an extraordinarily vivid account of the events and experience of persecution.

After Scheyer’s death in 1949, his stepson, disliking the book’s anti-German rhetoric, destroyed the manuscript. Or thought he did. Recently, a carbon copy was found in the family’s attic by P.N. Singer, Scheyer’s step-grandson, who has translated and provided an epilogue.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Sep 27, 2016

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316272872

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use