By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

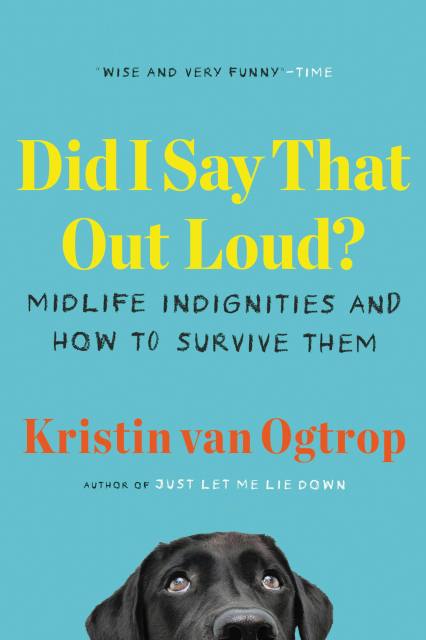

Did I Say That Out Loud?

Midlife Indignities and How to Survive Them

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 3, 2022

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316497503

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

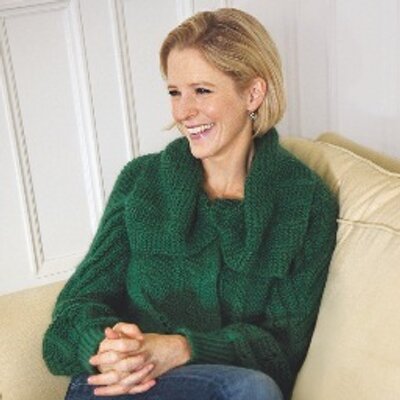

From the former editor-in-chief of Real Simple, enjoy this hilarious and deeply insightful take on the indignities of middle age and how to weather them with grace: “A pure pleasure to read” (Cathi Hanauer, author of Gone).

Do you hate the term “middle age?” So does Kristin van Ogtrop, who is still trying to come up with a less annoying way to describe those years when you find yourself both satisfied and outraged, confident and confused, full of appreciation but occasional disdain for the world around you. Like an intimate chat with your best friend, this mostly funny, sometimes sad, always affirming volume from longtime magazine journalist van Ogtrop is a celebration of that period of life when mild humiliations are significantly outweighed by a self-actualized triumph of the spirit. Finally!

Featuring stories from her own life, as well as anecdotes from her unwitting friends and family, van Ogtrop encourages you to laugh at the small irritations of midlife: neglectful children, stealth insomnia, forks that try to kill you, t.v. remotes that won’t find Netflix, abdominal muscles that can’t seem to get the job done. But also to acknowledge the things you may have lost: innocence, unbridled optimism, smooth skin. Dear friends. Parents. It’s all here: the sublime and the ridiculous, living together in the pages of this book as they do in your heart, like a big messy family, in this no-better-term-for-it middle age.

-

“Middle age is not for the faint of heart. But as these smart, wry essays make clear it’s also a glorious time of leaving others’ expectations behind.”People Magazine

-

“Wise and very funny… a tender but not treacly meditation on family and how we spend our time.”Time Magazine

-

“Van Ogtrop takes a humorous look at middle age in this insightful outing. Written 'for the woman who has perhaps stopped caring about things,' van Ogtrop’s essays are eminently relatable…Nearly every topic is fair game—droopy breasts, losing friends, and trying to keep up with her children as they jump from Facebook to Twitter to Instagram—and van Ogtrop’s tone is casual and welcoming. This thoughtful, quirky mix of meditations hits the spot.”Publishers Weekly (Starred Review)

-

“Full of hilarious thoughts, anecdotes and insights from that time in life where you can manage to be highly satisfied by life — while simultaneously outraged by everything.”New York Post

-

“One pearl of wisdom in veteran magazine editor Kristin van Ogtrop’s ultra-relatable memoir, Did I Say That Out Loud?, is our unofficial 2021 motto: 'Let’s just be happy to be here.' She bobs through midlife’s low points—swallowing a mysterious object and getting emergency surgery (check your salads, folks); leaving her job and losing a beloved black Lab—and comes up for air laughing.”Martha Stewart Living

-

“This truly laugh-out-loud collection of essays from the former editor-in-chief of Real Simple tackles aging, motherhood, her love of dogs, a medical odyssey, the demise of the magazine industry, and more."Zibby Owens, KatieCouric.com

-

“Did I Say That Out Loud? had me laughing out loud as I devoured these utterly relatable tales of work, family, love, and the sometimes tragic-comic mishaps that seem to happen more frequently as we reach a certain age. Each chapter is like a letter from a great friend—the cool, relatable friend who not only worked for Anna Wintour but also swallows household objects by accident. Kristin Van Ogtrop finds the perfect blend of humor and poignant honesty in this wonderfully original collection of essays.”Ann Leary, author of The Good House

-

“Mourning the demise of a high-flying career, dear old friends, and her younger body, Kristin van Ogtrop explores the secrets and delights of life at fifty-six with humor and candor—reassuring us that, however distressing it may be, getting older is way better than the alternative.”Ada Calhoun, author of Why We Can't Sleep

-

“Okay, yeah, maybe the lady-parts party is over, but this book is the funnier, more fun after party, and my old crone-womb breathed a sigh of relief (inaudibly I hope). Kristin van Ogtrop is so brisk and hilarious, so trustworthy and grateful and delightfully done with all the same things I'm done with that I kept saying, out loud, ‘Exactly!' and ‘THANK YOU.’”Catherine Newman, author of How to Be a Person

-

“Reading Did I Say That Out Loud? is like sitting down with a bottle of wine and your best girlfriends, talking and laughing long into the night. Toenails, insomnia, pets, parenting, careers, Botox, bosses—all the hard won pain and joy of making it to middle age are here. Thankfully, Kristin van Ogtrop holds nothing back. Read this book and give copies to all your friends.”Ann Hood, author of Kitchen Yarns and Comfort

-

“Like a long-awaited coffee with your smartest, savviest friend, Did I Say That Out Loud? offers comfort, connection, and cackles of the best kind of laughter—the kind that makes you feel not just understood, but seen.”KJ Dell’Antonia, New York Times bestselling author of The Chicken Sisters

-

"When I saw the tagline of this new book of personal essays—‘midlife indignities and how to survive them’—it rose to the top of my nightstand book pile. I felt comforted, self-forgiving, and highly amused in equal measure.”Carol Brooks, Editorial Director, First For Women

-

“This book abounds with wisdom and humor, poignancy and warmth. Whether exploring the midlife fall from corporate (or corporeal) grace, the tragic loss of a family dog, or the literal if beloved mess of raising three sons in the suburbs, Kristin van Ogtrop is candid, inspired, and a pure pleasure to read.”Cathi Hanauer, New York Times bestselling author of Gone and The Bitch Is Back

-

"Full of humor, heart, and humility, Kristin Van Ogtrop’s essays capture the mantra of the first piece in this perfect collection of meditations on middle age: Just happy to be here. I loved this book."Laura Zigman, author of Separation Anxiety

-

“Smart, funny, and unfailingly honest, Kristin van Ogtrop is the ideal companion for traversing the bumpy roads of midlife. Whether chronicling the rollercoaster of insomnia, the challenge of parenting people who inexplicably consider themselves adults, the experience of walking away from a career no longer worth salvaging, or the disappearance of a beloved dog, Kristin van Ogtrop finds meaning in the mayhem. Did I Say That Out Loud? is not only beautifully written, but is grounded in gratitude, which makes this collection both a comfort and a delight.”Karen Dukess, author of The Last Book Party

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use