By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

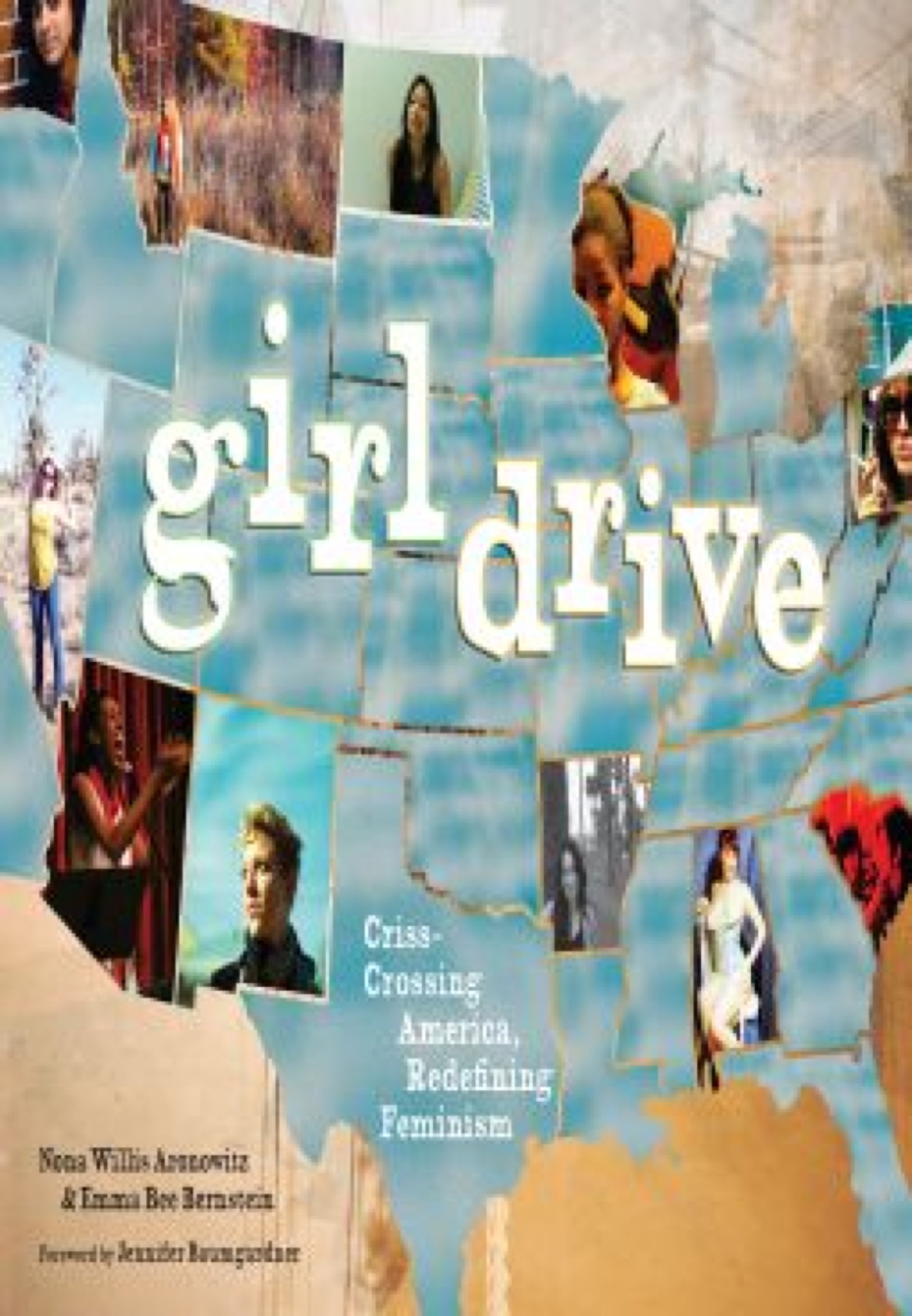

Girldrive

Criss-Crossing America, Redefining Feminism

Contributors

By Emma Bee Bernstein

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 24, 2009

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780786750450

Price

$13.99Price

$17.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $13.99 $17.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 24, 2009. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

What do young women care about? What are their hopes, worries, and ambitions? Have they heard of feminism, and do they relate to it?

These are just a few of the questions journalist Nona Willis Aronowitz and photographer Emma Bee Bernstein set out to answer in Girldrive. In October 2007, Aronowitz and Bernstein took a cross-country road trip to meet with the 127 women profiled in this book, ranging from well-known feminists like Kathleen Hanna, Laura Kipnis, Erica Jong, and Michele Wallace, to women who don’t relate to feminism at all. The result of these interviews, Girldrive is a regional chronicle of the struggles, concerns, successes, and insights of young women who are grappling—just as hard as their mothers and grandmothers did—to find, define, and fight for gender equity.

These are just a few of the questions journalist Nona Willis Aronowitz and photographer Emma Bee Bernstein set out to answer in Girldrive. In October 2007, Aronowitz and Bernstein took a cross-country road trip to meet with the 127 women profiled in this book, ranging from well-known feminists like Kathleen Hanna, Laura Kipnis, Erica Jong, and Michele Wallace, to women who don’t relate to feminism at all. The result of these interviews, Girldrive is a regional chronicle of the struggles, concerns, successes, and insights of young women who are grappling—just as hard as their mothers and grandmothers did—to find, define, and fight for gender equity.