Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

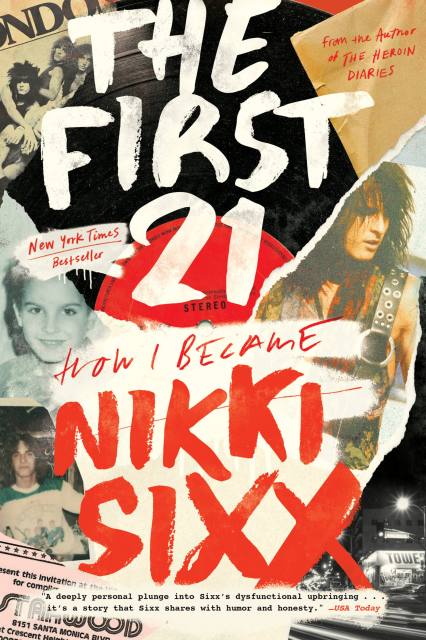

The First 21

How I Became Nikki Sixx

Contributors

By Nikki Sixx

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 8, 2022

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306923715

Price

$18.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 8, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

**New York Times Bestseller**

Rock-and-roll icon and three-time bestselling author Nikki Sixx tells his origin story: how Frank Feranna became Nikki Sixx, chronicling his fascinating journey from irrepressible Idaho farmboy to the man who formed the revolutionary rock group Mötley Crüe.

Nikki Sixx is one of the most respected, recognizable, and entrepreneurial icons in the music industry. As the founder of Mötley Crüe, who is now in his twenty-first year of sobriety, Sixx is incredibly passionate about his craft and wonderfully open about his life in rock and roll, and as a person of the world. Born Franklin Carlton Feranna on December 11, 1958, young Frankie was abandoned by his father and partly raised by his mother, a woman who was ahead of her time but deeply troubled. Frankie ended up living with his grandparents, bouncing from farm to farm and state to state. He was an all-American kid—hunting, fishing, chasing girls, and playing football—but underneath it all, there was a burning desire for more, and that more was music. He eventually took a Greyhound bound for Hollywood.

In Los Angeles, Frank lived with his aunt and his uncle—the president of Capitol Records—for a short time. But there was no easy path to the top. He was soon on his own. There were dead-end jobs: dipping circuit boards, clerking at liquor and record stores, selling used light bulbs, and hustling to survive. But at night, Frank honed his craft, joining Sister, a band formed by fellow hard-rock veteran Blackie Lawless, and formed a group of his own: London, the precursor of Mötley Crüe. Turning down an offer to join Randy Rhoads’s band, Frank changed his name to Nikki London, Nikki Nine, and, finally, Nikki Sixx. Like Huck Finn with a stolen guitar, he had a vision: a group that combined punk, glam, and hard rock into the biggest, most theatrical and irresistible package the world had ever seen. With hard work, passion, and some luck, the vision manifested in reality—and this is a profound true story finding identity, of how Frank Feranna became Nikki Sixx. It’s also a road map to the ways you can overcome anything, and achieve all of your goals, if only you put your mind to it.

Rock-and-roll icon and three-time bestselling author Nikki Sixx tells his origin story: how Frank Feranna became Nikki Sixx, chronicling his fascinating journey from irrepressible Idaho farmboy to the man who formed the revolutionary rock group Mötley Crüe.

Nikki Sixx is one of the most respected, recognizable, and entrepreneurial icons in the music industry. As the founder of Mötley Crüe, who is now in his twenty-first year of sobriety, Sixx is incredibly passionate about his craft and wonderfully open about his life in rock and roll, and as a person of the world. Born Franklin Carlton Feranna on December 11, 1958, young Frankie was abandoned by his father and partly raised by his mother, a woman who was ahead of her time but deeply troubled. Frankie ended up living with his grandparents, bouncing from farm to farm and state to state. He was an all-American kid—hunting, fishing, chasing girls, and playing football—but underneath it all, there was a burning desire for more, and that more was music. He eventually took a Greyhound bound for Hollywood.

In Los Angeles, Frank lived with his aunt and his uncle—the president of Capitol Records—for a short time. But there was no easy path to the top. He was soon on his own. There were dead-end jobs: dipping circuit boards, clerking at liquor and record stores, selling used light bulbs, and hustling to survive. But at night, Frank honed his craft, joining Sister, a band formed by fellow hard-rock veteran Blackie Lawless, and formed a group of his own: London, the precursor of Mötley Crüe. Turning down an offer to join Randy Rhoads’s band, Frank changed his name to Nikki London, Nikki Nine, and, finally, Nikki Sixx. Like Huck Finn with a stolen guitar, he had a vision: a group that combined punk, glam, and hard rock into the biggest, most theatrical and irresistible package the world had ever seen. With hard work, passion, and some luck, the vision manifested in reality—and this is a profound true story finding identity, of how Frank Feranna became Nikki Sixx. It’s also a road map to the ways you can overcome anything, and achieve all of your goals, if only you put your mind to it.

-

“A deeply personal plunge into Sixx’s dysfunctional upbringing….The journey from Feranna to Sixx – a name he maybe, sort of stole from another local musician who had dubbed himself Niki Syxx – is a fraught and complicated one. But it’s a story that Sixx shares with humor and honesty."USA Today

-

“ Amazing... The First 21: How I Became Nikki Sixx is the origin story many have been waiting for…. There are many poignant moments and stunning revelations. You’ll learn how he went from sweeping floors to selling out shows at The Starwood, the artists and authors who inspired him, the meaning behind the trademark black lines he wears onstage, how he ripped off everything from Johnny Thunders’ look to the name Nikki Sixx, and how James Caan almost lassoed him poolside. However, his determination to succeed is the real story.”The Aquarian

-

"[Nikki] writes it in a way where the reader feels like they're there."Dr. Phil

-

"This book is so exciting...I love the backstory of [Nikki's] life...What a great book."Matt Pinfield, "New & Approved"

-

“[The First 21] explores how [Nikki Sixx’s] hand-to-mouth upbringing made him hungry to see his rock-band dreams come to fruition…thoughtful glimpses into the backstory of a very determined musician.”Kirkus Reviews

-

“[Nikki Sixx] follows his searing memoir, The Heroin Diaries, with an equally exhilarating look at the first 21 years of his life… Fans will relish this passionate look at the man behind the hair.“Publishers Weekly

-

“The First 21: How I Became Nikki Sixx, is an up-and-comers blueprint to creating one of the biggest bands ever."The Festivals Hub

-

“A fascinating read, one that Sixx tells with candor and an awareness of self that few possess.”Audio Ink Radio

-

“This is a profound true story finding identity, of how Frank Feranna became Nikki Sixx. It's also a road map to the ways you can overcome anything, and achieve all of your goals, if only you put your mind to it.”BraveWords

-

“[The First 21 is] illuminating and insightful… very honest – painfully so.”Cleveland.com

-

"This is Sixx’s origin story, filled with adventures and misadventures as well as a surprising amount of warmth that puts flesh and heart into the miscreant image he cultivated."Macomb Daily

-

“There’s surprisingly no shortage of new stories to behold here. Perhaps the most fascinating are the lesser known ones; Sixx finally dives deep into the history of pre-Crüe acts such as Sister and London, and working with the likes of W.A.S.P. frontman Blackie Lawless (among others)…. Do yourself the favor of getting to know [Sixx] a little better by reading this book, and you might just be glad you do.”Rewind It Magazine