Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

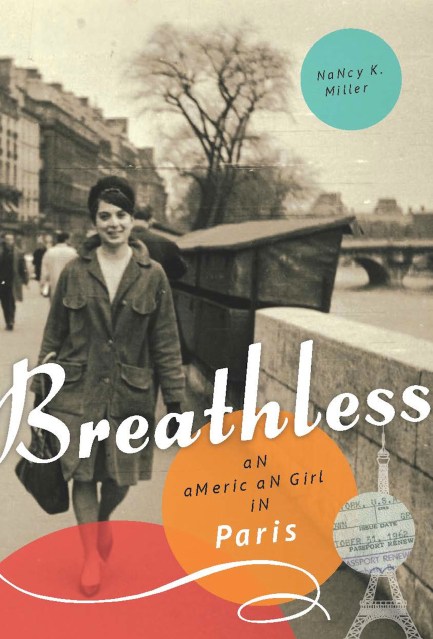

Breathless

An American Girl in Paris

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 5, 2013

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580054898

Price

$7.99Price

$9.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $7.99 $9.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 5, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In the early 1960s, most middle-class American women in their twenties had their lives laid out for them: marriage, children, and life in the suburbs. Most, but not all. Breathless is the story of a girl who represents those who rebelled against conventional expectations.

Paris was a magnet for those eager to resist domesticity, and like many young women of the decade, Nancy K. Miller was enamored of everything French—from perfume and Hermès scarves to the writing of Simone de Beauvoir and the New Wave films of Jeanne Moreau. After graduating from Barnard College in 1961, Miller set out for a year in Paris, with a plan to take classes at the Sorbonne and live out a great romantic life inspired by the movies. After a string of sexual misadventures, she gave up her short-lived freedom and married an American expatriate who promised her a lifetime of three-star meals and five-star hotels. But her husband wasn't who he said he was, and she eventually had to leave Paris and her dreams behind.

This stunning memoir chronicles a young woman’s coming-of-age tale, and offers a glimpse into the intimate lives of girls before feminism.