Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

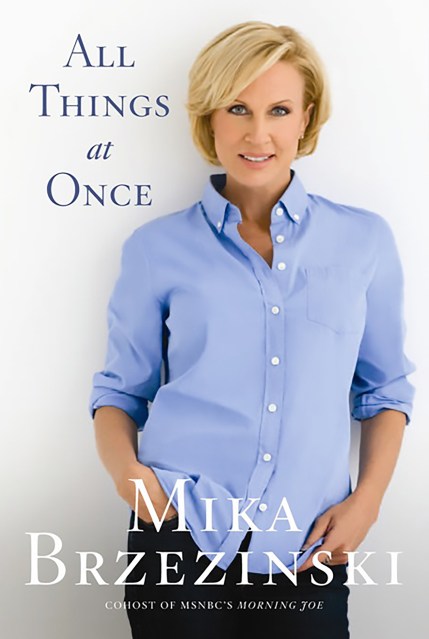

All Things At Once

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $9.99 $12.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 5, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

But success hasn't always come easy for Mika. Growing up the only daughter of former national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski, she struggled to find an identity in a family of overachievers. She worked her way up the ranks of network television to surpass even her own ambitions, reaching the very top of the ladder, only to get canned less than a year later. After an unsuccessful stint as a stay-at-home mom, Mika went back to the workplace with encouragement from her eight-year-old daughter. She decided to start all over again with a beginner's job at age forty, a step back that proved to be a brilliant career move. Mika stumbled into Morning Joe and the rest is history. Now, in a time when many women are losing their jobs or struggling to find the perfect balance between work and home, Mika guides women of all ages to a place where they can find peace and fulfillment in their lives.

In the tradition of Gail Sheehy's classic Passages, this illuminating book shows women how to reach their full potential in all areas of life and at every stage of their journey. Blending the personal with the prescriptive, Brzezinski's book will address the perpetual question of how to “have it all” when it comes to work and family; the importance of remaining equally humble in the face of great success and seemingly devastating setbacks; as well as the necessity of knowing and embracing our limitations so that we may transcend them.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Jan 5, 2010

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781602861183

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use