By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

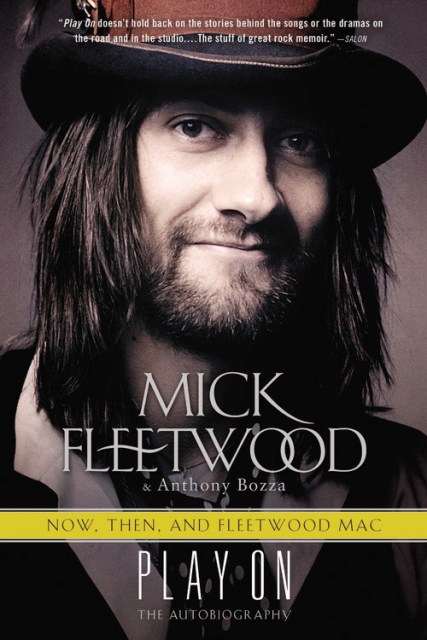

Play On

Now, Then, and Fleetwood Mac: The Autobiography

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 16, 2014

- Page Count

- 448 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316403573

Price

$43.00Price

$54.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover (Large Print) $43.00 $54.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 16, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

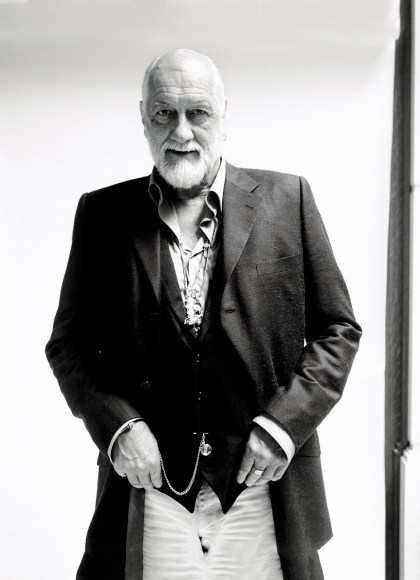

“After forty-six years of being on the road, this is the right time to look back in a way I’ve never done before: now and then. This is the story of my life in rock and roll — and how the band that has meant everything to me came to define me. I’m looking forward to sharing it with you.”

Mick Fleetwood has been a member of the ever-evolving Fleetwood Mac, one of the world’s most successful and adored bands, for over four decades. Here he tells the full and candid story of his life as one of music’s greatest drummers and bandleaders, the cofounder of the deeply loved supergroup that bears his name and that of his bandmate and lifelong friend John McVie. In this intimate portrait of a life lived in music, Fleetwood vividly recalls his upbringing tapping along to every song playing on the radio, his experiences as a musician in ’60s London, and the earliest permutation of the band featuring Peter Green.

Play On sheds new light on Fleetwood Mac’s raucous history, describing the highs and lows of being in the band that Fleetwood was determined to keep together. Here he reflects on the creation of landmark albums such as Rumours and Tusk, the great loves of his life, and the many incredible and outrageous moments of recording, touring, and living with Fleetwood Mac. Fleetwood describes these moments with honesty and immediacy, taking us to the very heart of this multilayered journey that has always been anchored in music.

Through it all, from intense love to plaintive heartaches, from collaborations to confrontations, it’s been the drive to play on that has prevailed. Now, then, and always, it’s Fleetwood Mac.

Mick Fleetwood has been a member of the ever-evolving Fleetwood Mac, one of the world’s most successful and adored bands, for over four decades. Here he tells the full and candid story of his life as one of music’s greatest drummers and bandleaders, the cofounder of the deeply loved supergroup that bears his name and that of his bandmate and lifelong friend John McVie. In this intimate portrait of a life lived in music, Fleetwood vividly recalls his upbringing tapping along to every song playing on the radio, his experiences as a musician in ’60s London, and the earliest permutation of the band featuring Peter Green.

Play On sheds new light on Fleetwood Mac’s raucous history, describing the highs and lows of being in the band that Fleetwood was determined to keep together. Here he reflects on the creation of landmark albums such as Rumours and Tusk, the great loves of his life, and the many incredible and outrageous moments of recording, touring, and living with Fleetwood Mac. Fleetwood describes these moments with honesty and immediacy, taking us to the very heart of this multilayered journey that has always been anchored in music.

Through it all, from intense love to plaintive heartaches, from collaborations to confrontations, it’s been the drive to play on that has prevailed. Now, then, and always, it’s Fleetwood Mac.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use