Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

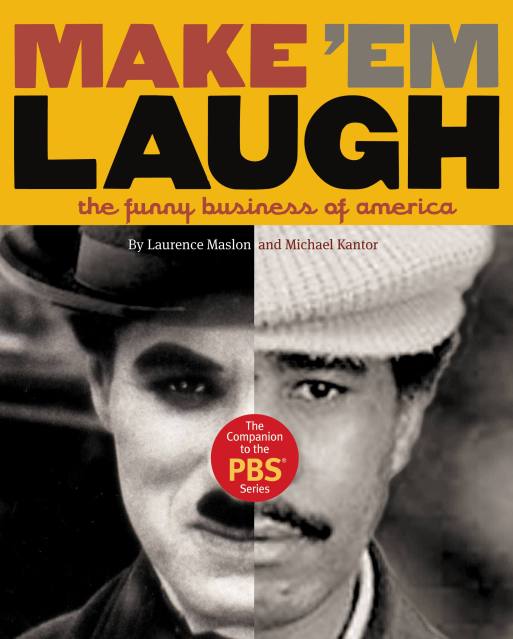

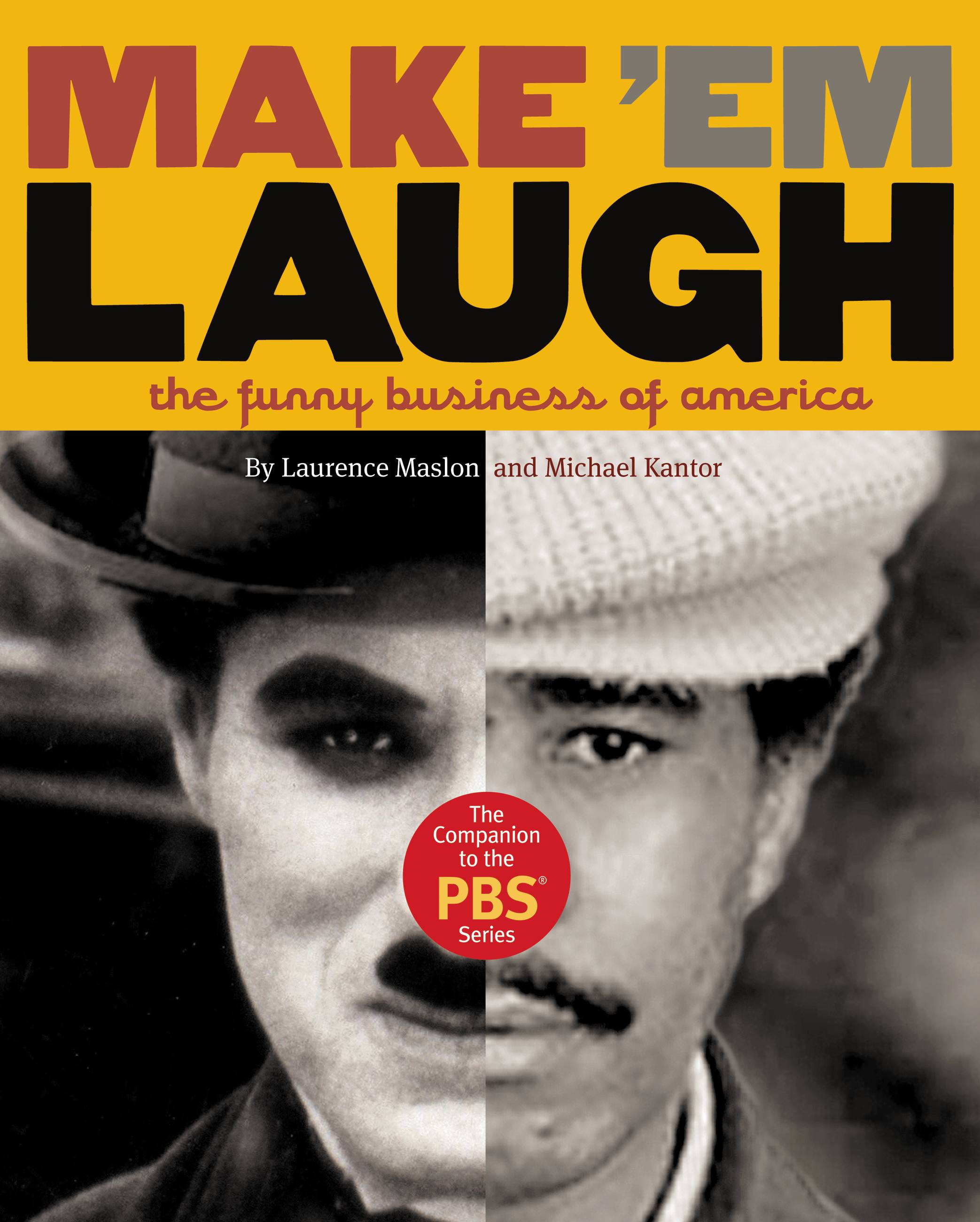

Make ‘Em Laugh

The Funny Business of America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 2, 2008

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9780446555753

Price

$22.99Price

$29.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $22.99 $29.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 2, 2008. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Each of the six chapters focuses a different style or archetype of comedy, from the slapstick pratfalls of Buster Keaton and Lucille Ball through the wiseguy put-downs of Groucho Marx and Larry David, to the incendiary bombshells of Mae West and Richard Pryor . And at every turn the significance of these comedians-smashing social boundaries, challenging the definition of good taste, speaking the truth to the powerful-is vividly tangible. Make ‘Em Laugh is more than a compendium of American comic genius; it is a window onto the way comedy both reflects the world and changes it-one laugh at a time.

Starting from the groundbreaking PBS series, the authors have gone deeper into the works and lives of America’s great comic artists, with biographical portraits, archival materials, cultural overviews, and rare photos. Brilliantly illustrated, with insights (and jokes) from comedians, writers and producers, along with film, radio, television, and theater historians, Make ‘Em Laugh is an indispensible, definitive book about comedy in America.