Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

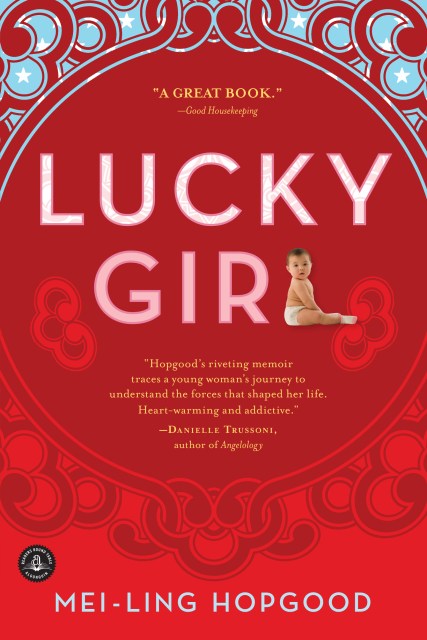

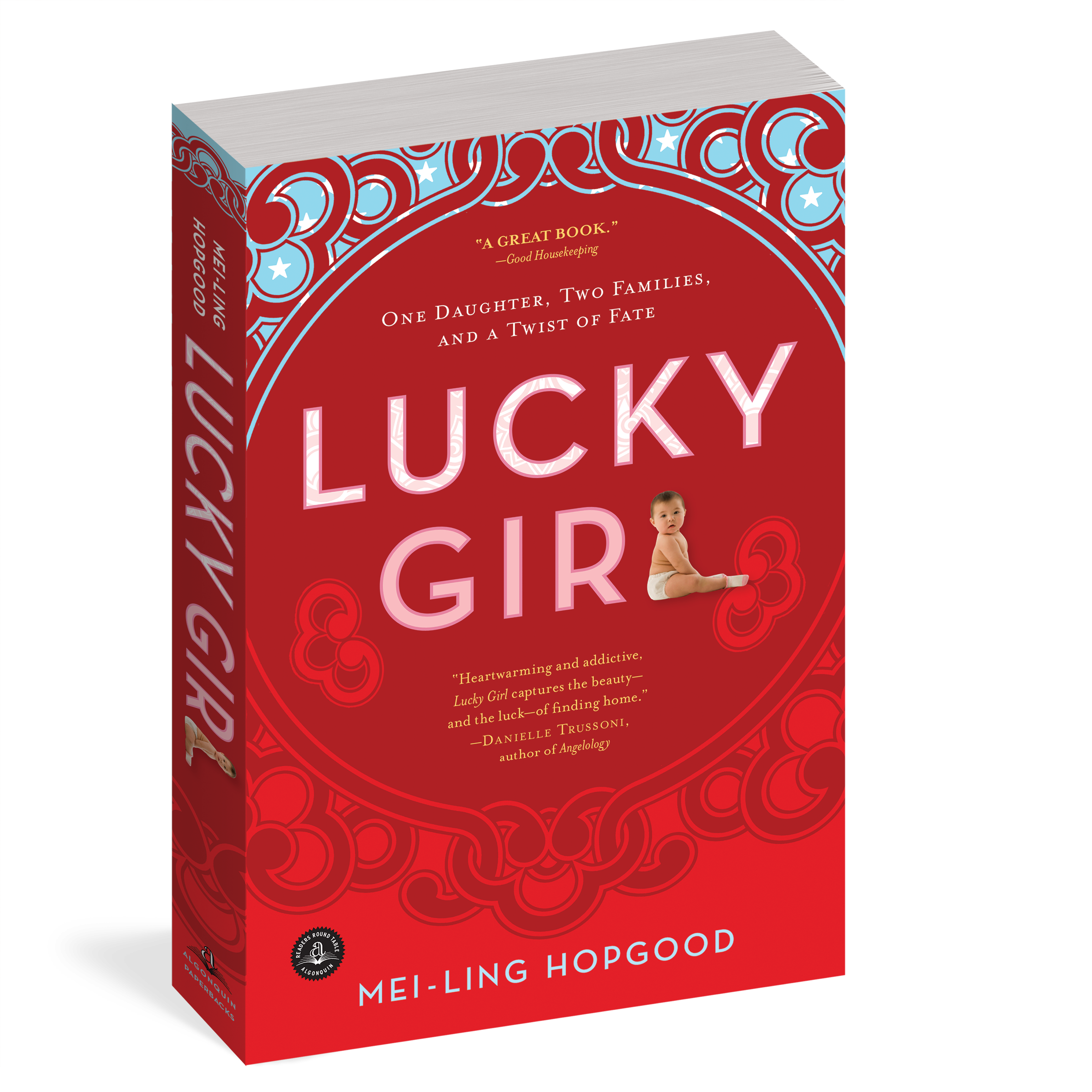

Lucky Girl

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$13.95Price

$18.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $13.95 $18.95 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 15, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In a true story of family ties, journalist Mei-Ling Hopgood, one of the first wave of Asian adoptees to arrive in America, comes face to face with her past when her Chinese birth family suddenly requests a reunion after more than two decades.

In 1974, a baby girl from Taiwan arrived in America, the newly adopted child of a loving couple in Michigan. Mei-Ling Hopgood had an all-American upbringing, never really identifying with her Asian roots or harboring a desire to uncover her ancestry. She believed that she was lucky to have escaped a life that was surely one of poverty and misery, to grow up comfortable with her doting parents and brothers.

Then, when she’s in her twenties, her birth family comes calling. Not the rural peasants she expected, they are a boisterous, loving, bossy, complicated middle-class family who hound her daily—by phone, fax, and letter, in a language she doesn’t understand—until she returns to Taiwan to meet them. As her sisters and parents pull her into their lives, claiming her as one of their own, the devastating secrets that still haunt this family begin to emerge. Spanning cultures and continents, Lucky Girl brings home a tale of joy and regret, hilarity, deep sadness, and great discovery as the author untangles the unlikely strands that formed her destiny.

Genre:

-

Mei-Ling Hopgood "writes with humor and grace about her efforts to understand how biology, chance, choice and love intersect to delineate a life. A wise, moving meditation on the meaning of family, identity and fate." –KirkusDetroit Metro Times

-

”A journalist by trade, Hopgood pushes herself to ask tough questions. As she does, shocking family secrets begin to spill forth. . . Brutally honest. . . Although Hopgood’s memoir is uniquely her own, multiple perspectives on adoption saturate the book.” –Bust magazineGood Housekeeping

-

“An award-winning writer recounts her experience as one of the first Chinese babies adopted in the West and her surprising trail back to the rural Taiwanese family who gave her away. . . A great book.”B>Good HousekeepingLouisville Courier-Journal

-

“With concise, truth-seeking deftness of a seasoned journalist, Mei-Ling delves into the political, cultural and financial reasoning behind her Chinese birth parents' decision to put her up for adoption. . . Cut with historical detail and touching accounts of Mei-Ling's "real" family, the Hopgoods, Lucky Girl is a refreshingly upbeat take on dealing with the pressures and expectations of family, while remaining true to oneself. Simple, to the point and uncluttered of the everyday minutiae, Mei-Ling Hopgood nails the concept of becoming one's own.”Detroit Metro Times

-

"An award-winning writer recounts her experience as one of the first Chinese babies adopted in the West and her surprising trail back to the rural Taiwanese family who gave her away . . . A great book."Good Housekeeping

-

"Enchanting . . . Hopgood's story entices not because it's joyful but because she is honest, analytical and articulate concerning her ambivalence about and eventual acceptance of both her families and herself."Louisville Courier-Journal

- On Sale

- Jun 15, 2010

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Algonquin Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781565129825

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use