By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

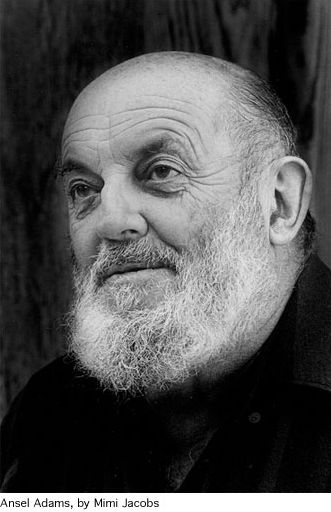

Ansel Adams: An Autobiography

Contributors

By Ansel Adams

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 1, 1996

- Page Count

- 360 pages

- Publisher

- Ansel Adams

- ISBN-13

- 9780821222416

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook (Digital original) $11.99 $15.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 1, 1996. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Discover this “evocative celebration of the life, career, friendships, concerns, and vision” of Ansel Adams, America’s greatest photographer (New York Times)

“No lover of Ansel Adams’ photographs can afford to miss this book.” – Wallace Stegner

Illustrated with eight pages of Adams’ gorgeous black-and-white photographs, this book brings readers behind the images into the stories and circumstances of their creation. Written with characteristic warmth, vigor, and wit, this fascinating account brings to life the infectious enthusiasms, fervent battles, and bountiful friendships of a truly American original.

“A warm, discursive, and salty document.” – New Yorker

-

"Rough-edged...witty and candid...A direct line to Adams' thoughts and ideas."Los Angeles Times

-

"An evocative celebration of the life, career, friendships, concerns, and vision of an ardent environmentalist and pioneering artist who captured the rich natural beauty of America through the lens of his camera."New York Times

-

"A warm, discursive, and salty document"New Yorker

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use