By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

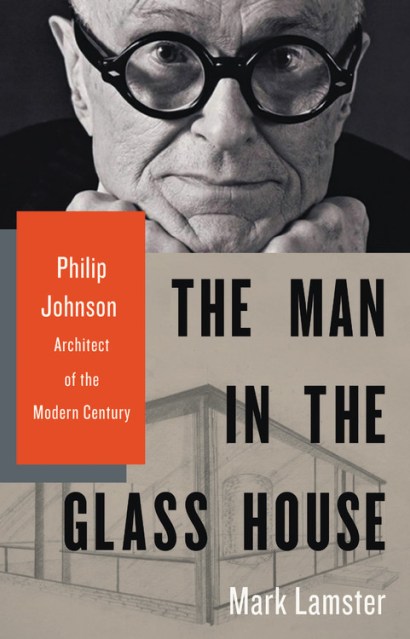

The Man in the Glass House

Philip Johnson, Architect of the Modern Century

Contributors

By Mark Lamster

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 528 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316126434

Price

$45.00Price

$57.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $45.00 $57.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A “smoothly written and fair-minded” (Wall Street Journal) biography of architect Philip Johnson — a finalist for the National Book Critic’s Circle Award.

When Philip Johnson died in 2005 at the age of 98, he was still one of the most recognizable and influential figures on the American cultural landscape. The first recipient of the Pritzker Prize and MoMA’s founding architectural curator, Johnson made his mark as one of America’s leading architects with his famous Glass House in New Caanan, CT, and his controversial AT&T Building in NYC, among many others in nearly every city in the country — but his most natural role was as a consummate power broker and shaper of public opinion.

Johnson introduced European modernism — the sleek, glass-and-steel architecture that now dominates our cities — to America, and mentored generations of architects, designers, and artists to follow. He defined the era of “starchitecture” with its flamboyant buildings and celebrity designers who esteemed aesthetics and style above all other concerns. But Johnson was also a man of deep paradoxes: he was a Nazi sympathizer, a designer of synagogues, an enfant terrible into his old age, a populist, and a snob. His clients ranged from the Rockefellers to televangelists to Donald Trump.

Award-winning architectural critic and biographer Mark Lamster’s The Man in the Glass House lifts the veil on Johnson’s controversial and endlessly contradictory life to tell the story of a charming yet deeply flawed man. A rollercoaster tale of the perils of wealth, privilege, and ambition, this book probes the dynamics of American culture that made him so powerful, and tells the story of the built environment in modern America.

When Philip Johnson died in 2005 at the age of 98, he was still one of the most recognizable and influential figures on the American cultural landscape. The first recipient of the Pritzker Prize and MoMA’s founding architectural curator, Johnson made his mark as one of America’s leading architects with his famous Glass House in New Caanan, CT, and his controversial AT&T Building in NYC, among many others in nearly every city in the country — but his most natural role was as a consummate power broker and shaper of public opinion.

Johnson introduced European modernism — the sleek, glass-and-steel architecture that now dominates our cities — to America, and mentored generations of architects, designers, and artists to follow. He defined the era of “starchitecture” with its flamboyant buildings and celebrity designers who esteemed aesthetics and style above all other concerns. But Johnson was also a man of deep paradoxes: he was a Nazi sympathizer, a designer of synagogues, an enfant terrible into his old age, a populist, and a snob. His clients ranged from the Rockefellers to televangelists to Donald Trump.

Award-winning architectural critic and biographer Mark Lamster’s The Man in the Glass House lifts the veil on Johnson’s controversial and endlessly contradictory life to tell the story of a charming yet deeply flawed man. A rollercoaster tale of the perils of wealth, privilege, and ambition, this book probes the dynamics of American culture that made him so powerful, and tells the story of the built environment in modern America.

-

One of the Best Books of the Year - Smithsonian Magazine

-

"Smoothly written and fair-minded... [a] searching and thorough overview of Johnson's engrossing life."Wall Street Journal

-

"[a] brisk, clear-eyed new biography... Johnson emerges in Lamster's treatment as a person of utter consistency, determined in every instance to strip architecture of social purpose."the New Yorker

-

"Searing yet judicious... thoroughly documented and convincingly laid out... [an] insightful investigation."The New York Review of Books

-

"The perfect addition to the aesthete's bookshelf... essential"The Globe and Mail

-

"[A] thoroughly researched and highly readable volume that vividly captures the essence of a complex and disturbing character."Architectural Record

-

"The Man in the Glass House is a vivid, thoughtful, illuminating, disturbing, and definitive chronicle of one of twentieth-century architecture's most celebrated and powerful figures."Kurt Andersen, author and host of Studio 360

-

"Mark Lamster thoughtfully teases out the real history of this modernist icon, from his impressive sexual appetites and more-than-flirtation with fascism in Hitler's Germany to his 1990s collaboration with Donald Trump. It's clear that Johnson was a fascinating and disturbing figure; Lamster's biography, impressively and honestly, displays him with his full complexity."Ruth Franklin, author of Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life

-

"More than a dozen years after his death Philip Johnson remains a perplexing, polarizing, magnetic and frustrating figure: although he was far from our greatest architect, no one did more to shape our architectural culture. In this compelling biography, Mark Lamster deconstructs Johnson's complex persona, evaluates his work and begins the complex process of establishing his place in history."Paul Goldberger, Pulitzer Prize-winning critic and author of Building Art: The Life and Work of Frank Gehry

-

"Philip Johnson was as complicated and contradictory as the American century that created him and which he helped define. Modernist, reactionary, anti-Semite, populist, artist, and commercial powerhouse, he lived, in some sense, to contradict himself. In Mark Lamster's nuanced telling, Johnson becomes more than the man in the round glasses or the avatar of modernism; he becomes a symbol of America itself. This is biography as history, and it is a magnificent piece of work."David L. Ulin, author of Sidewalking: Coming to Terms with Los Angeles

-

"The Man in the Glass House captures the essence of a prodigious, multivalent, enigmatic American talent with authority and aplomb. It's a biography with attitude, a bullet train through the shifting landscapes of twentieth-century America, and a sheer pleasure to read."Tom Vanderbilt, author of Traffic: Why We Drive The Way We Do

-

"Philip Johnson led many lives--as curator, aspiring demagogue with a Third Reich fixation, modernist architect, winking post-modernist, and finally kingmaker in the profession--and Mark Lamster has masterfully woven them together in a biography that is as much literary as critical achievement. Required reading for anyone hoping to make sense of the American century, for Johnson was its house architect."Christopher Hawthorne, Chief Design Officer for the city of Los Angeles and former architecture critic, Los Angeles Times

-

"An astute... look at the influential modernist architect. Offering a fresh look at his subject's less-than-savory aspects, Lamster portrays a diffident genius for whom being boring was the greatest crime."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"Lamster's mesmerizing, authoritative, and often-astonishing study grapples with Johnson's legacy in all its ambiguity... Lamster depicts a man by turns enchanting and irritating, sublime and subpar, pioneering and derivative... Johnson's contradictions, Lamster argues, reveal something of the nation's. Readers may come away with both contempt and admiration, a testament to Lamster's masterful achievement."Booklist (starred review)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use