By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

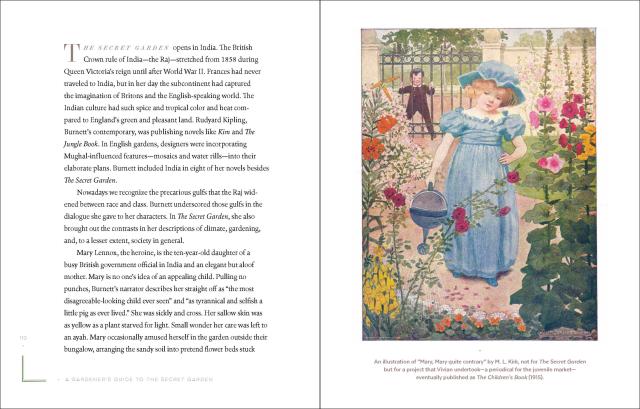

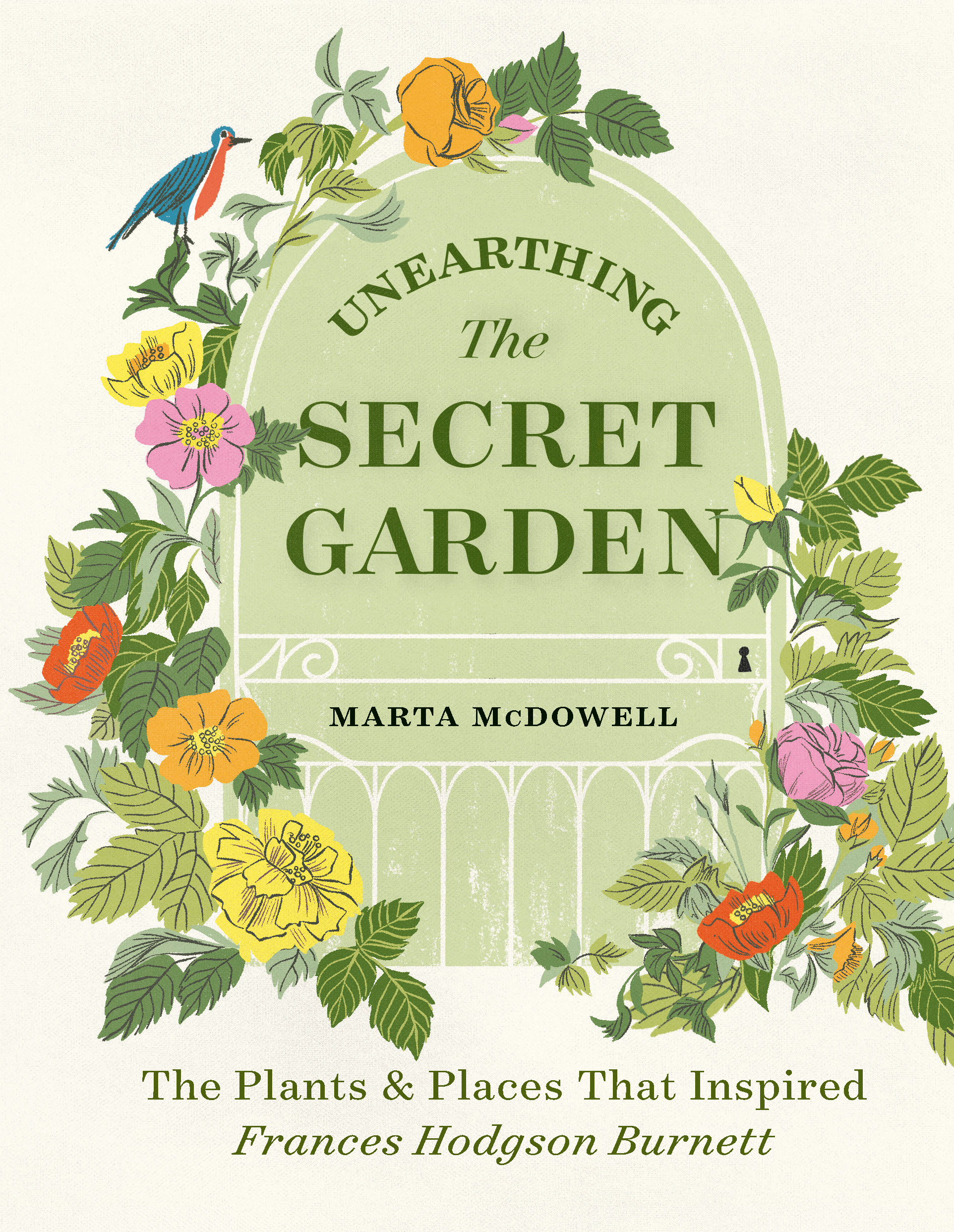

Unearthing The Secret Garden

The Plants and Places That Inspired Frances Hodgson Burnett

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 12, 2021

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604699906

Price

$25.95Price

$32.95 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $25.95 $32.95 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 12, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“With a sprightly tone, infectious enthusiasm, and a professor’s penchant for scholarly detail, McDowell brings keen insight and critical assessment to the life and works of this beloved author.” —Booklist

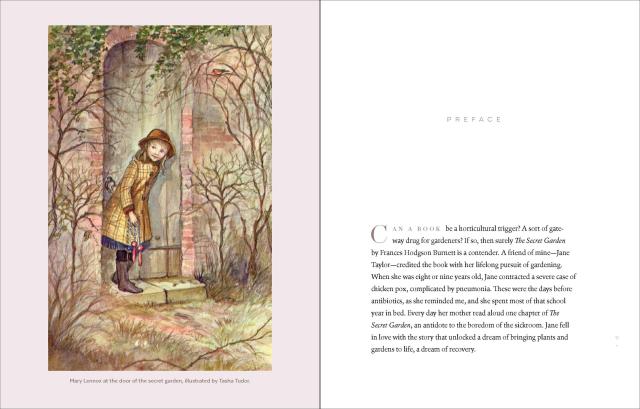

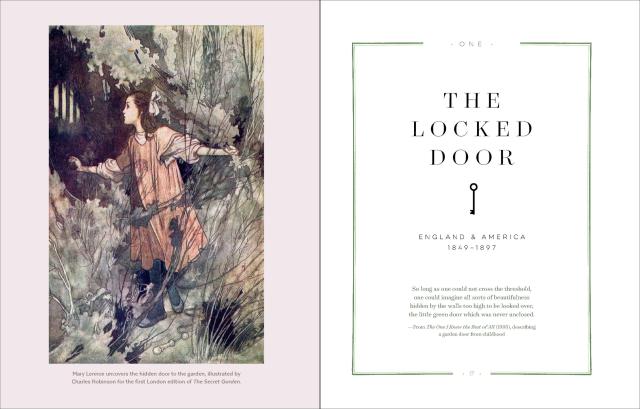

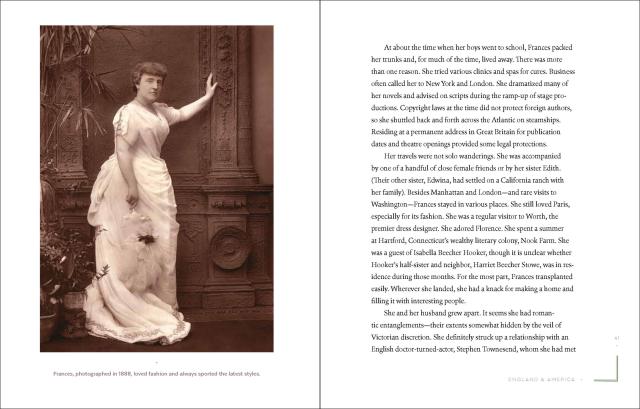

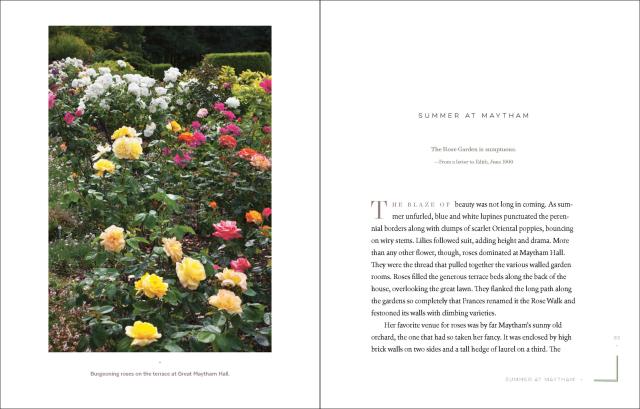

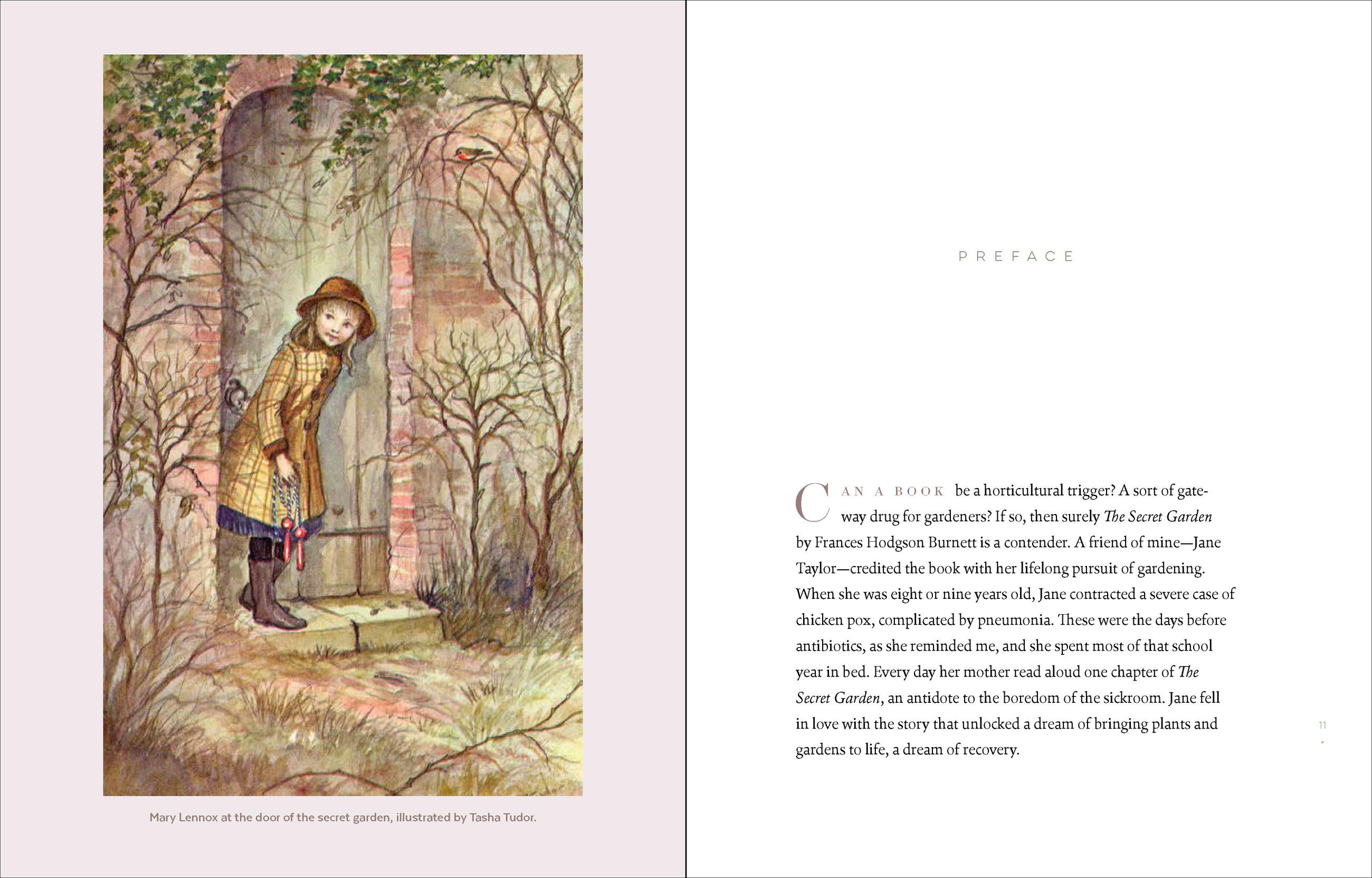

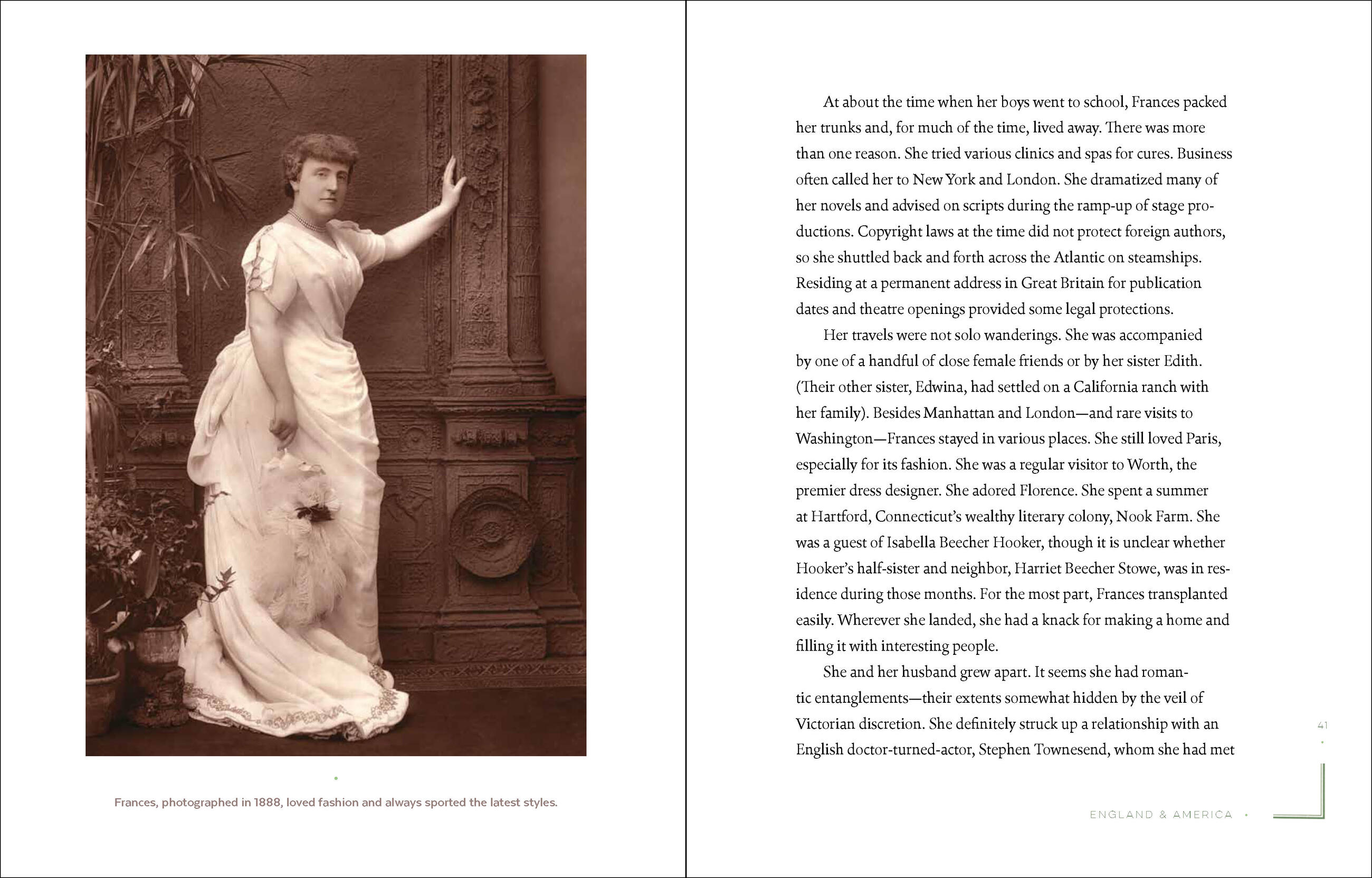

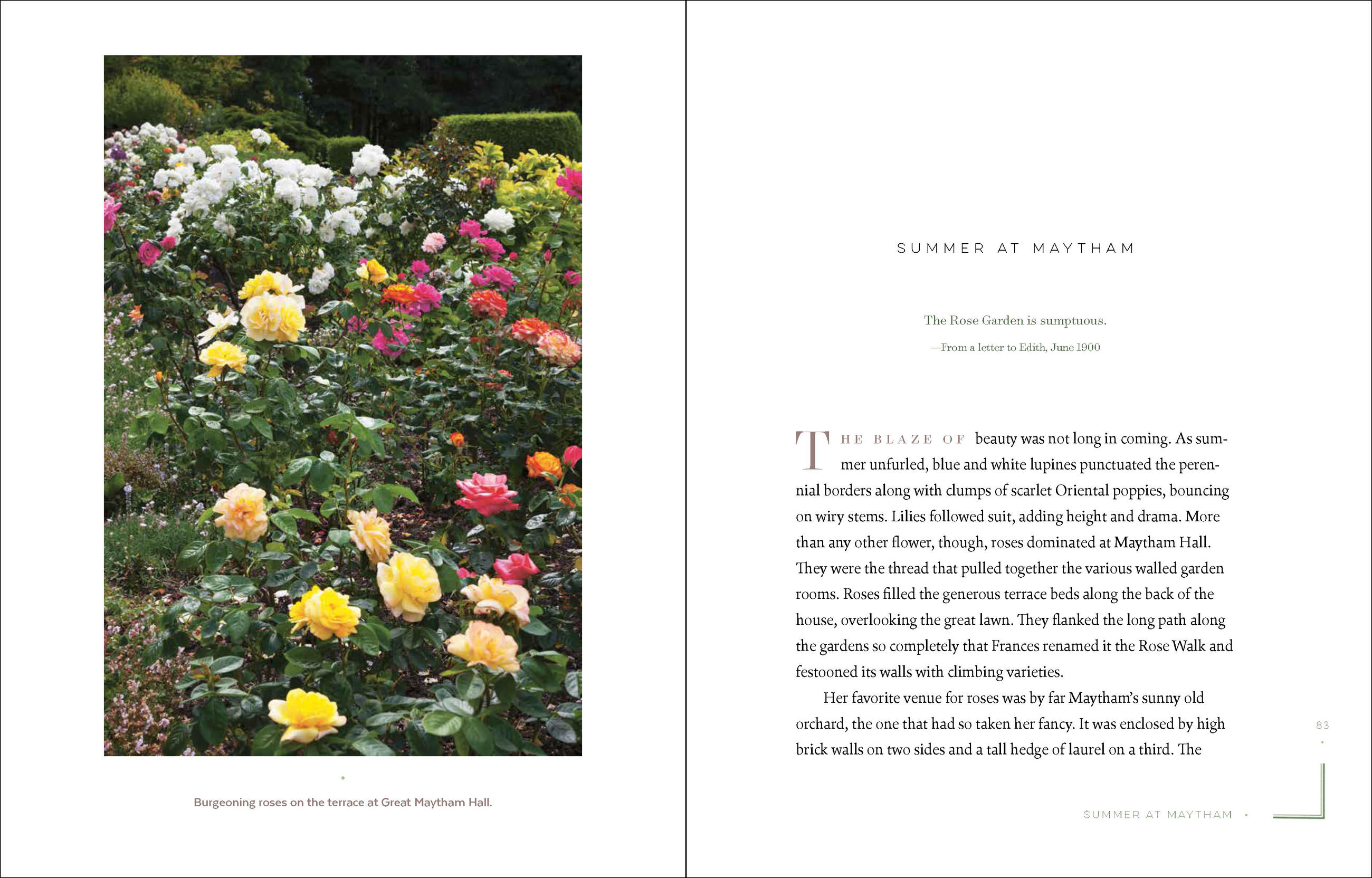

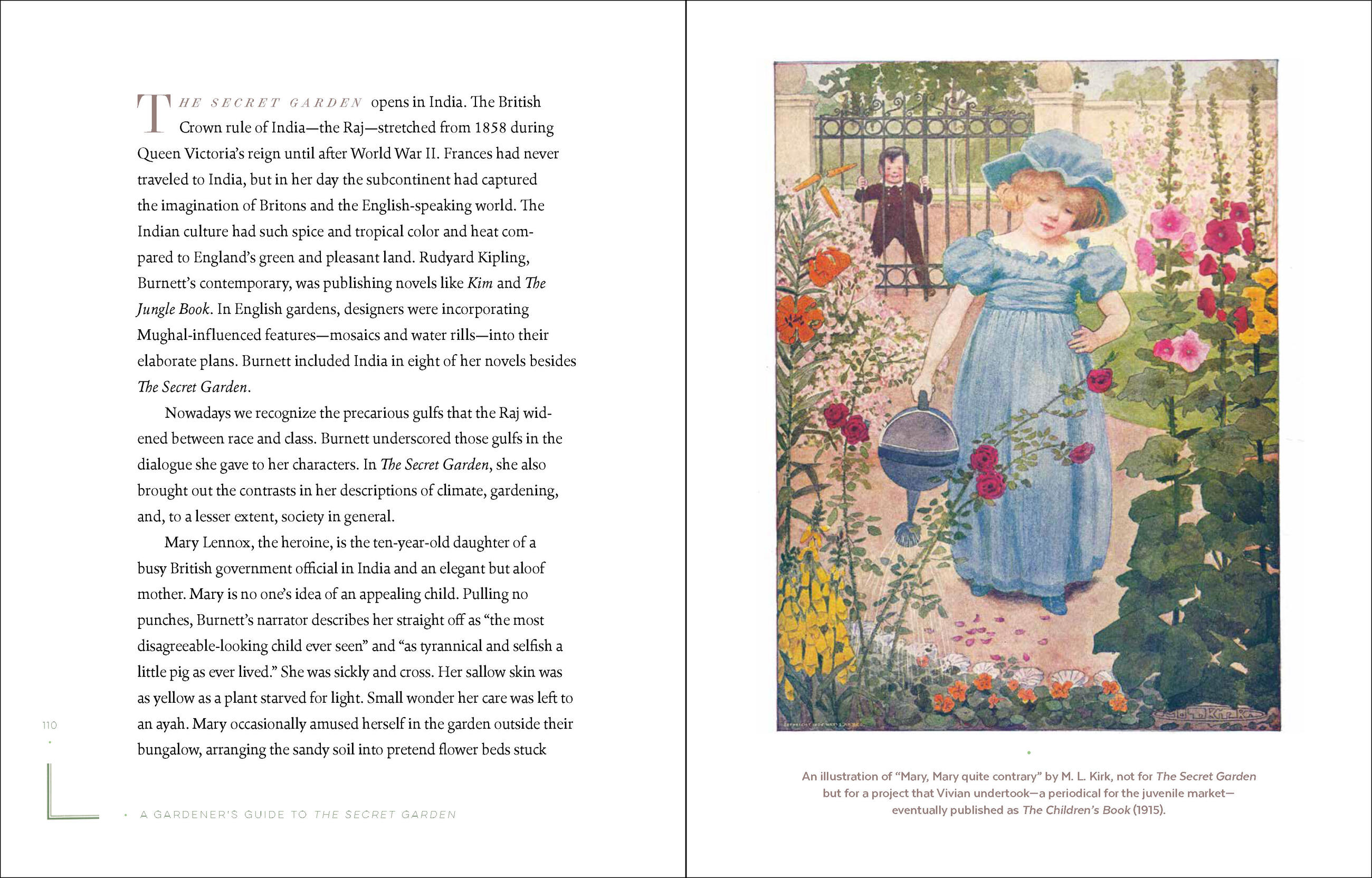

The Secret Garden is one of the most beloved children’s classics, and its author Frances Hodgson Burnett was not only a prolific writer but also a lover of flowers and gardens. In Unearthing The Secret Garden, Marta McDowell delves into Burnett’s professional and gardening life. McDowell chronicles how Burnett’s interest in gardens developed along with her work as a writer. Readers will learn about Burnett’s three gardens in England, Long Island, and Bermuda. Gardeners will delight in the guide to plats featured in The Secret Garden and McDowell’s transcriptions of three of Burnett’s garden-themed short stories. Throughout, the delightful text is complimented by period illustrations and contemporary photographs.

This deeply moving and gift-worthy book is a must-read for fans of The Secret Garden and anyone who loves the story behind the story.

-

“From walled and terraced flower beds can sprout beloved children’s fiction, as the historian Marta McDowell chronicles in Unearthing the Secret Garden.” I>The New York TimesThe Literary Ladies Guide “Marta McDowell comprehensively explores the esteemed author's life before her famous story and after it, and includes a guide to the book itself.” —Bas Bleu “McDowell will help us see how Burnett’s gardens evolved and were influenced by her book before, during and after its publication." —The Start Democrat “This charming book is a must-read for fans of The Secret Garden and anyone who loves the story behind the story.” —The Emporia Gazette

“Affectionate and informative, Unearthing the Secret Garden is not unlike a garden itself, with its smooth lawns of prose and striking shows of illustration and photography. As in Burnett’s enclosures at Maytham Hall, one is forever turning a corner—or, rather, a page—and coming across a fresh vista.” I>The Wall Street Journal

“With a sprightly tone, infectious enthusiasm, and a professor’s penchant for scholarly detail, McDowell brings keen insight and critical assessment to the life and works of this beloved author.” —Booklist

“This book is for anyone who loves reading or gardening or exploring the history of places and lives entwined.” —Gardens Illustrated

“Rich in details, lavish with illustrations, including many from the story’s various print versions, this book is a must-have for anyone whose first horticulture passions were triggered by hat gateway drug to gardening, otherwise known as The Secret Garden.” I>The Washington Gardener

“Blooming with photos, illustrations, and botanical paintings, McDowell’s gorgeous book opens an ivy-covered door to new information about one of the world’s most famous authors.”B>Angelica Shirley Carpenter, editor of In the Garden: Essays in Honor of Frances Hodgson Burnett

“McDowell’s beautiful writing and research take us all on an exclusive behind-the-scenes tour of a blooming world that has only existed in our imaginations, until now.”B>Keri Wilt, motivational speaker and writer and great-great-granddaughter of Frances Hodgson Burnett

“McDowell’s blending of this abiding fiction with its author’s real life is safe and sure. New readers—young and old—will be propelled into a faraway enchanted world now magically reawakened more than a hundred years on.”B>David Wheeler, editor, Hortus

“Unearthing the Secret Garden brings Burnett to life as someone the reader would happily meet, in or out of her various gardens, to sit in the shade with a cheerful robin nearby while talking of roses and flowers and life.” I>Bellwood Gardens

“Marta McDowell’s gorgeous, deeply felt tribute to the timeless tale. Filled with photographs of the flowers, plants, and gardens that inspired Burnett.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use