By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

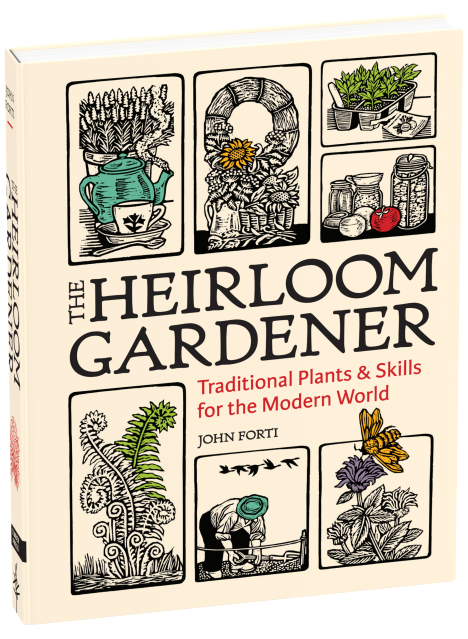

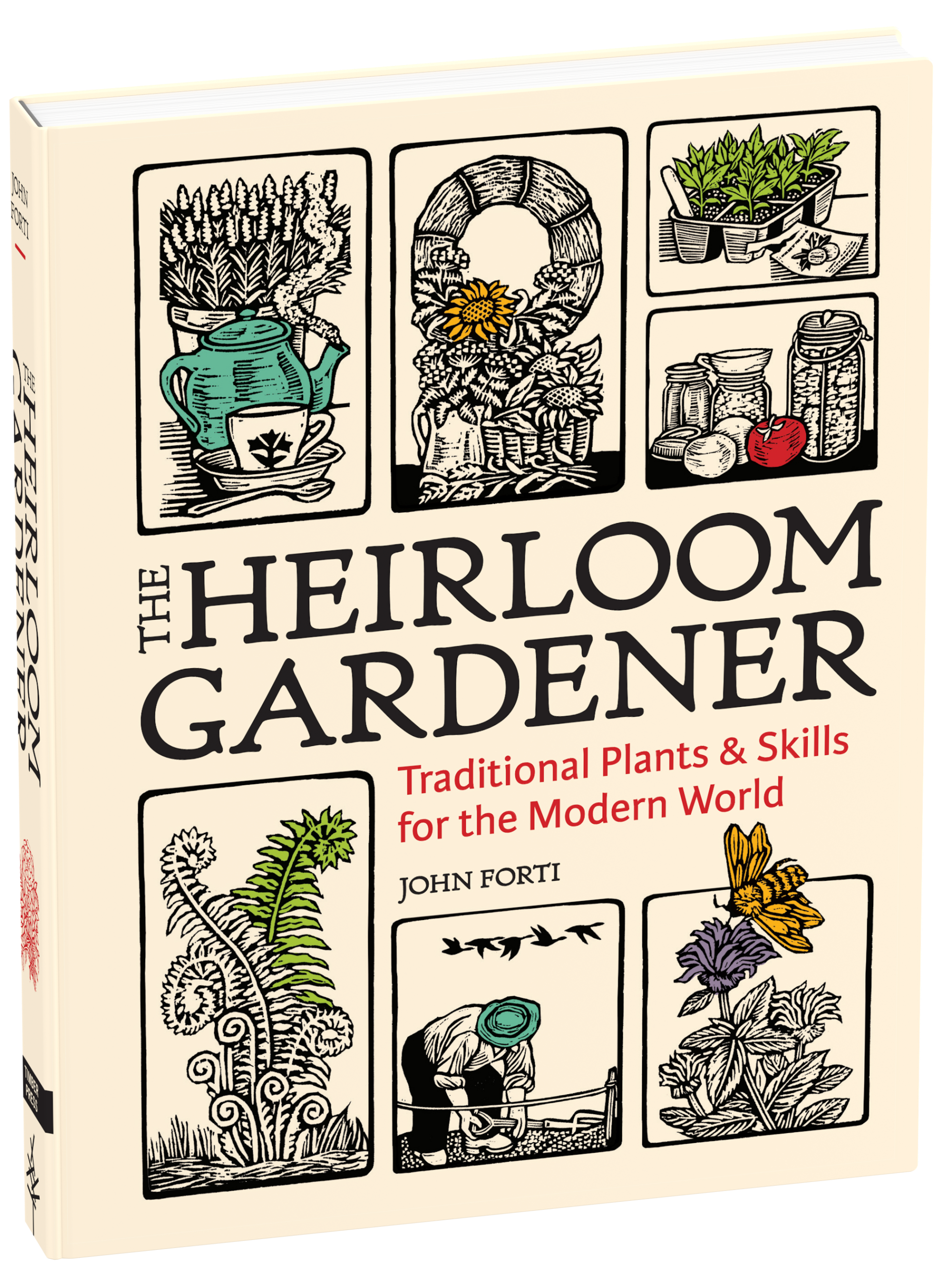

The Heirloom Gardener

Traditional Plants and Skills for the Modern World

Contributors

By John Forti

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 22, 2021

- Page Count

- 264 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604699937

Price

$30.00Price

$39.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $18.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 22, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“Part essay collection, part gardening guide, The Heirloom Gardener encourages readers to embrace heirloom seeds and traditions, serving as a well-needed reminder to slow down and reconnect with nature.” —Modern Farmer

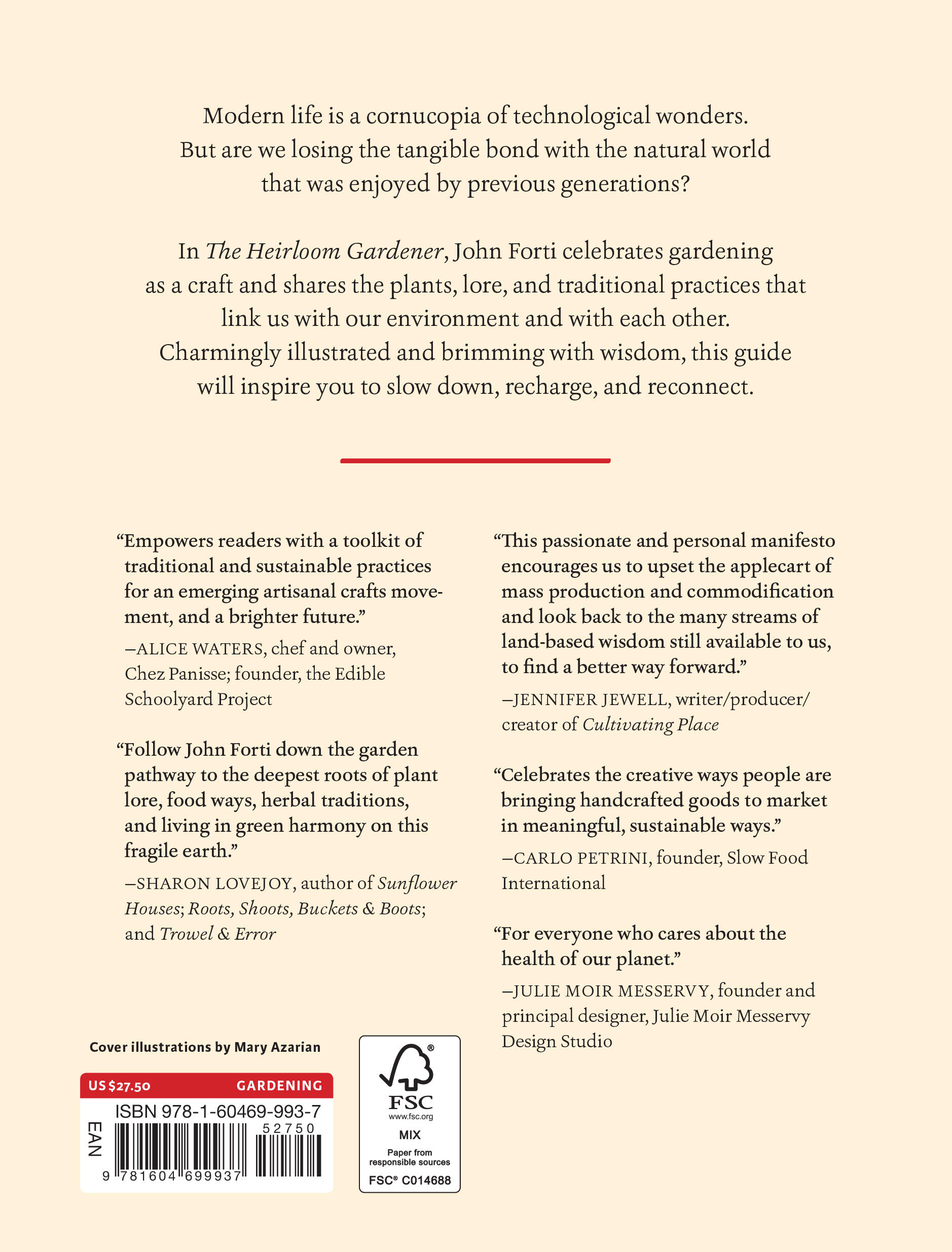

Modern life is a cornucopia of technological wonders. But is something precious being lost? A tangible bond with our natural world—the deep satisfaction of connecting to the earth that was enjoyed by previous generations?

In The Heirloom Gardener, John Forti celebrates gardening as a craft and shares the lore and traditional practices that link us with our environment and with each other. Charmingly illustrated and brimming with wisdom, this guide will inspire you to slow down, recharge, and reconnect.

-

“The Heirloom Gardener empowers readers with a toolkit of traditional and sustainable practices for an emerging artisanal crafts movement, and a brighter future.” —Alice Waters, chef and owner, Chez Panisse; founder, The Edible Schoolyard ProjectThe Wanderer “Garden historian John Forti eloquently shares his passion for heirloom plants, historic garden techniques, and traditional crafts…this book is sure to delight anyone interested in garden history and learning how to enjoy the fruits of the garden.” –The American Gardener

“Follow John Forti down the garden pathway to the deepest roots of plant lore, food ways, herbal traditions, and living in green harmony on this fragile earth.” —Sharon Lovejoy, author of Sunflower Houses; Roots, Shoots, Buckets Boots; and Trowel Error

“The author's essay collection enlightens and inspires… This book will encourage a tangible bond with the natural world, and the deep satisfaction of connecting to the earth that was enjoyed by previous generations.” I>The Michigan Gardener

“This passionate and personal manifesto encourages us to upset the applecart of mass production and commodification and look back to the many streams of land-based wisdom still available to us, to find a better way forward.” —Jennifer Jewell, writer/producer/creator of Cultivating Place

“Celebrates the creative ways people are bringing hand-crafted goods to market in meaningful, sustainable ways.” —Carlo Petrini, founder, Slow Food International

“The Heirloom Gardener is for everyone who cares about the health of our planet.” —Julie Moir Messervy, owner of Julie Moir Messervy Design Studio

“Forti’s groundbreaking book builds on shared roots to forge a stronger, better, greener tomorrow.” —Tovah Martin, author of The Garden in Every Sense and Season

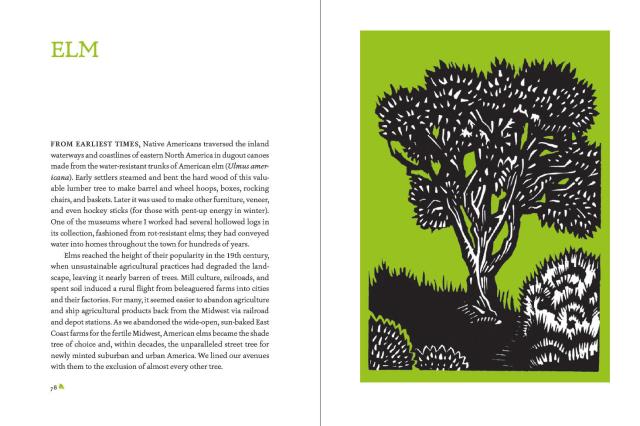

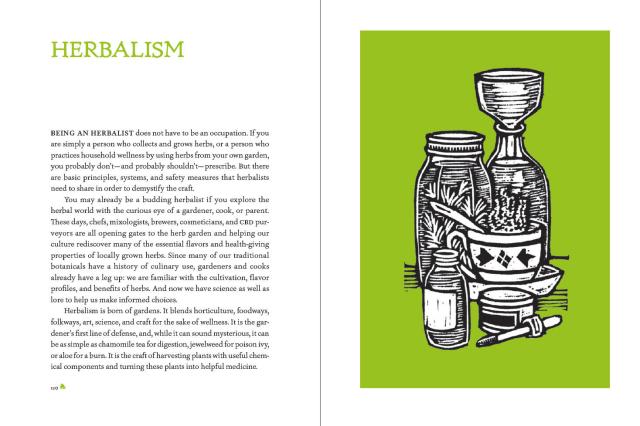

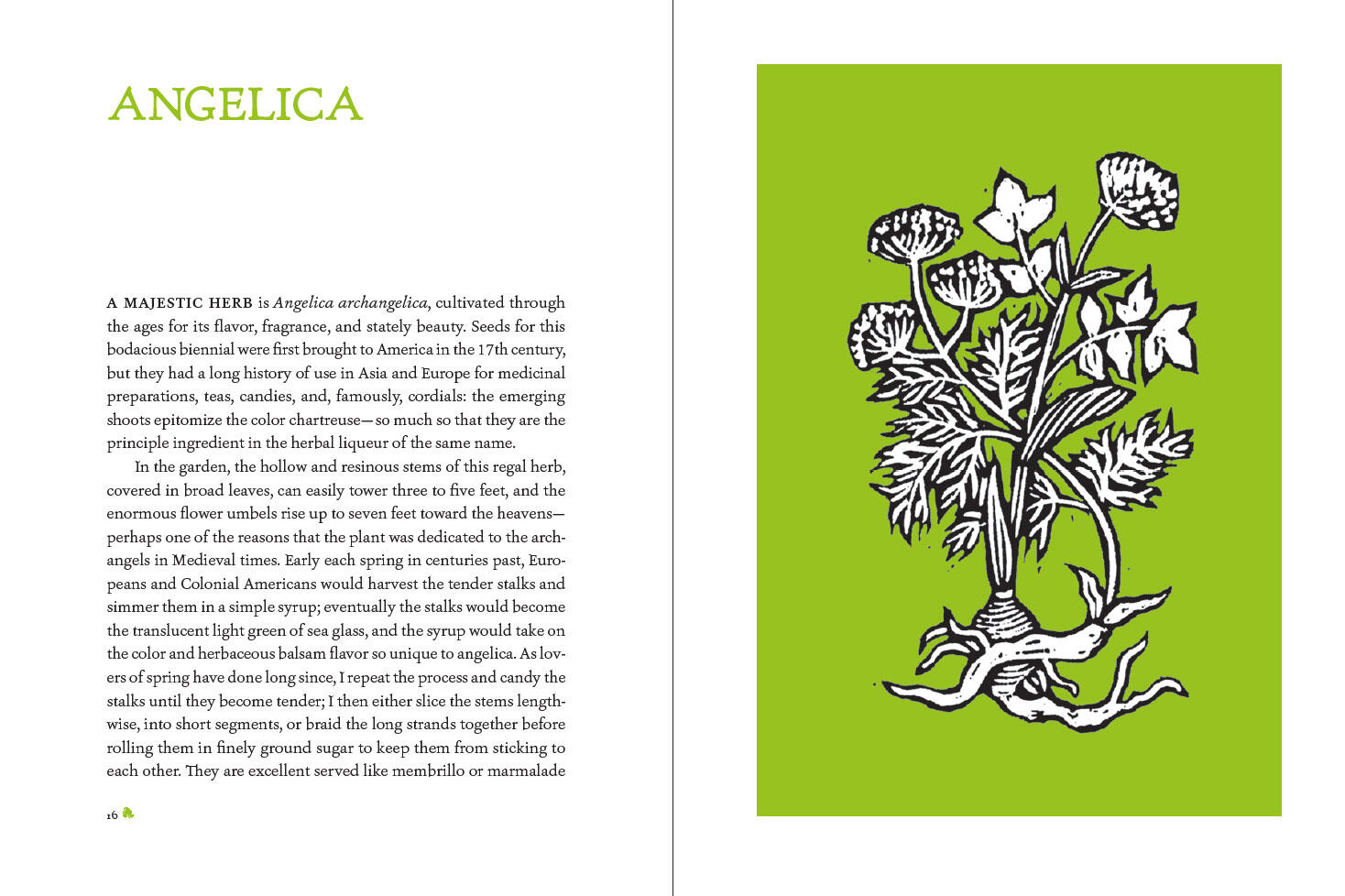

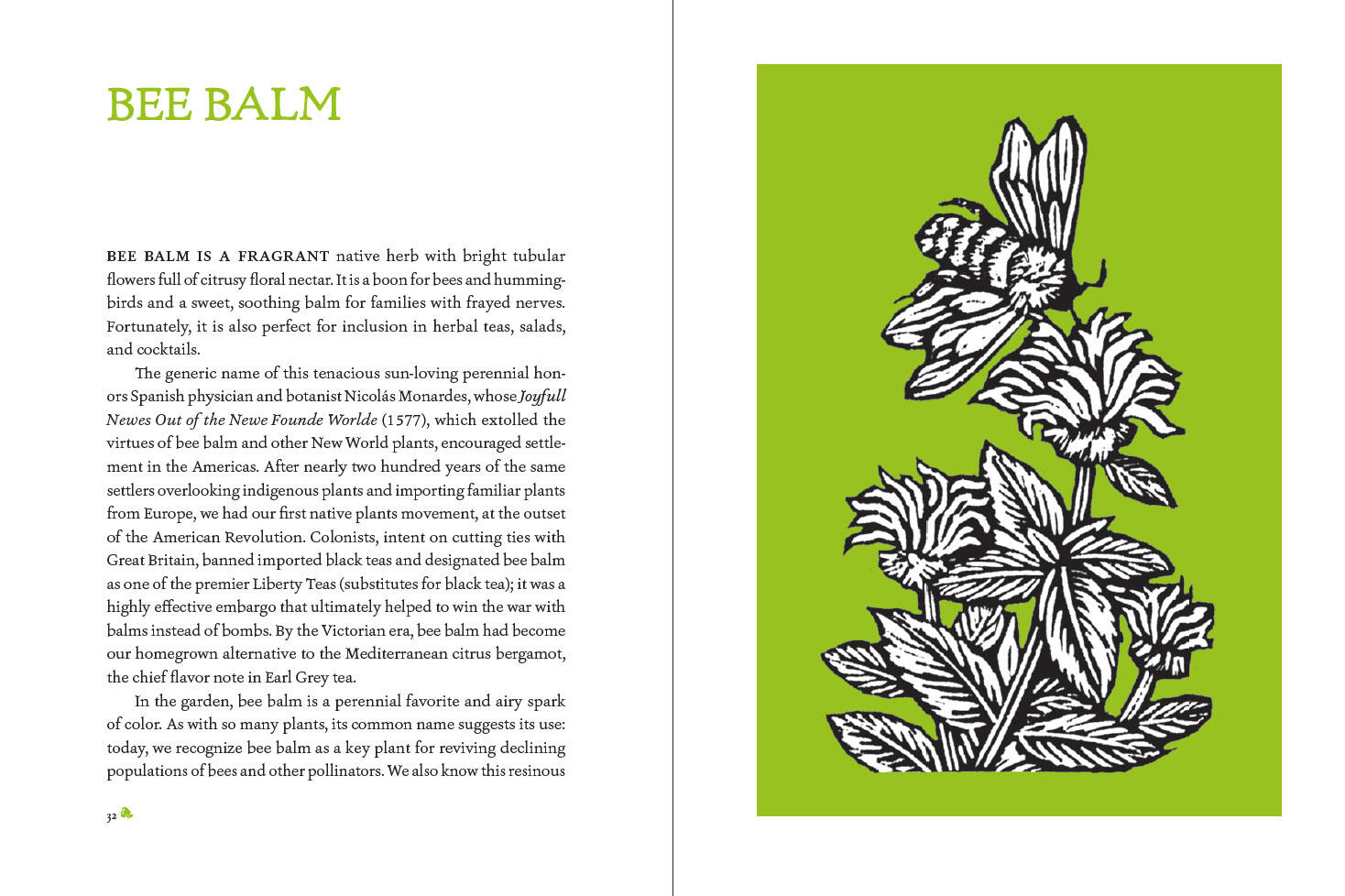

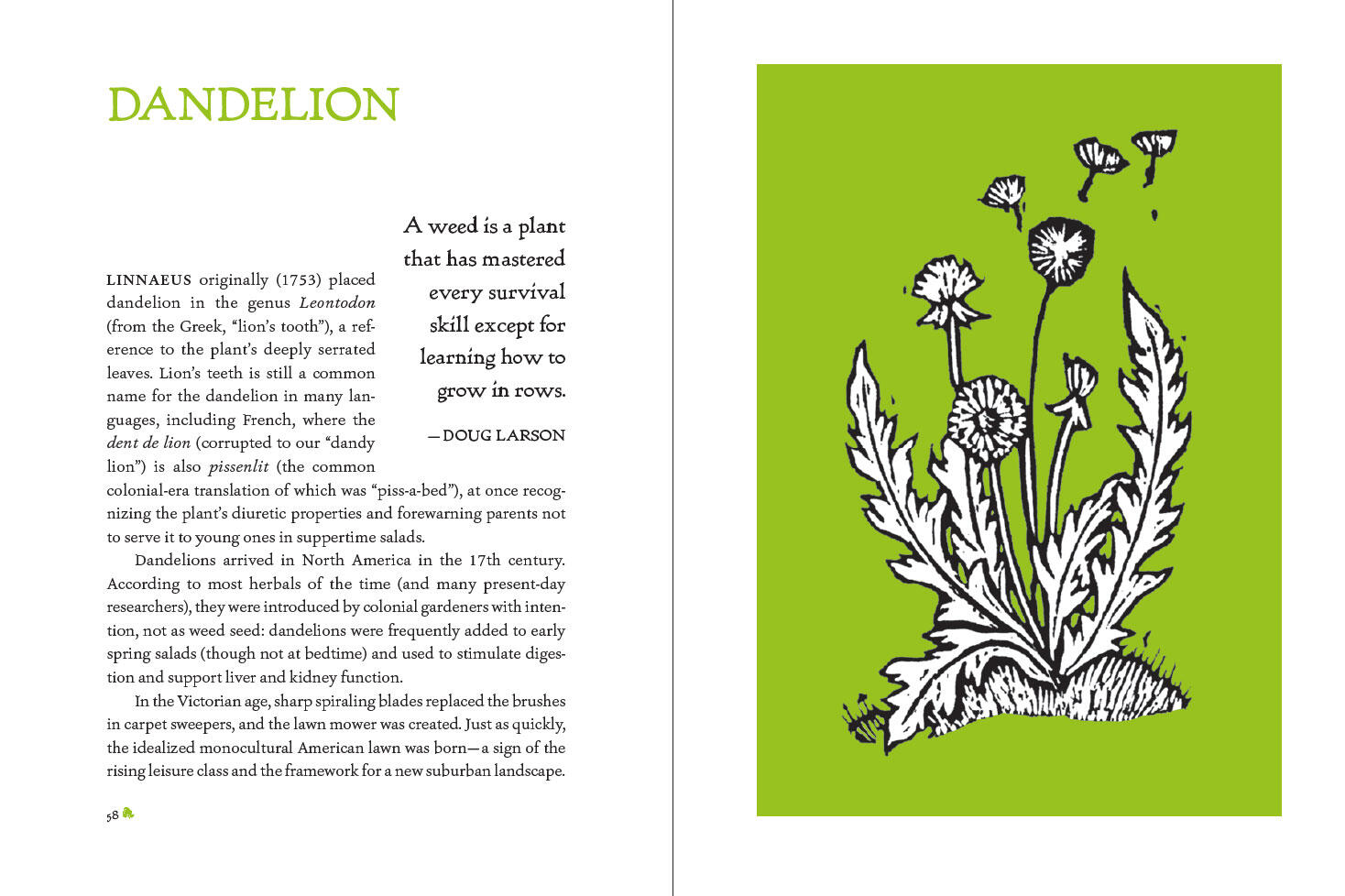

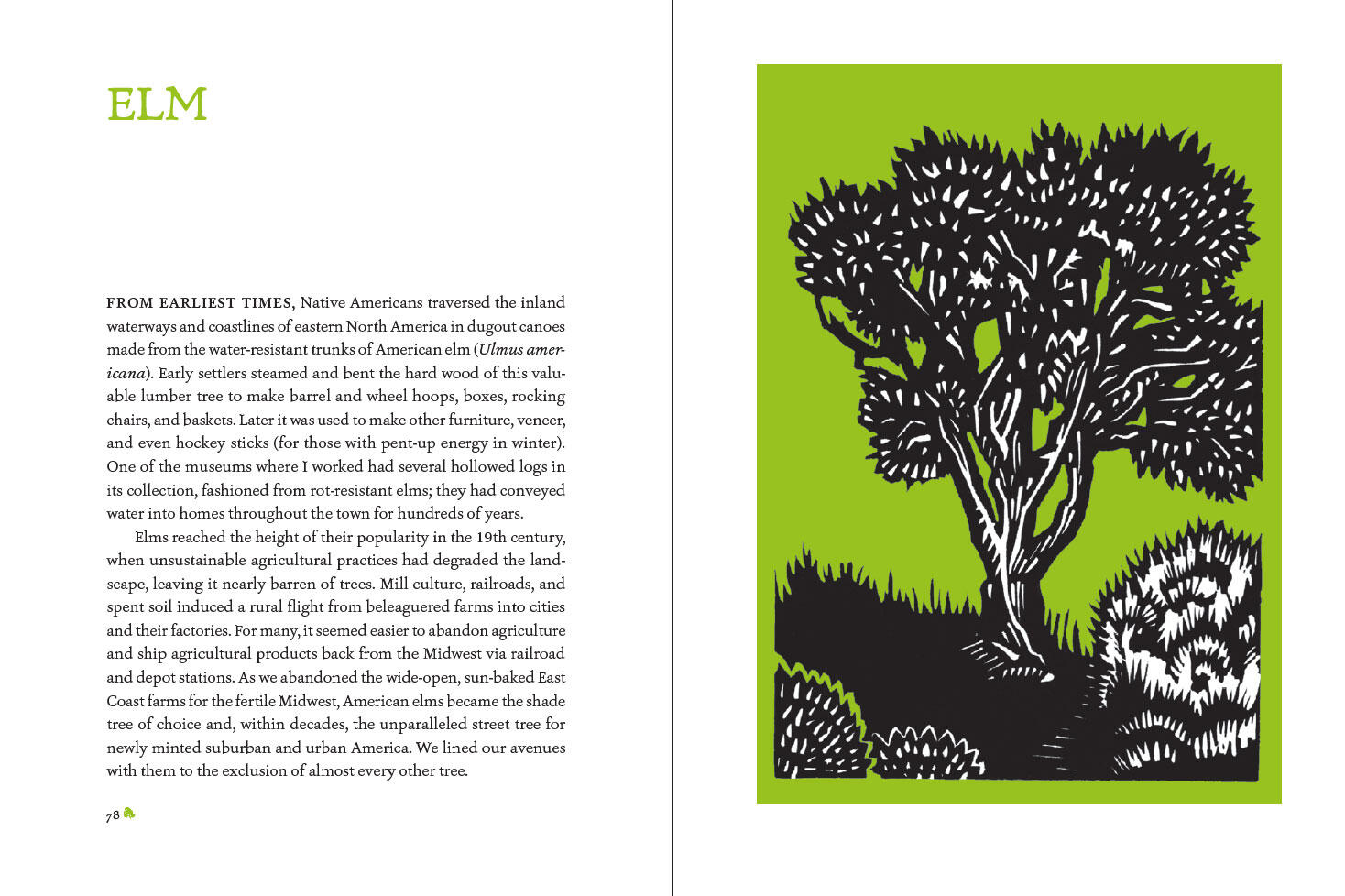

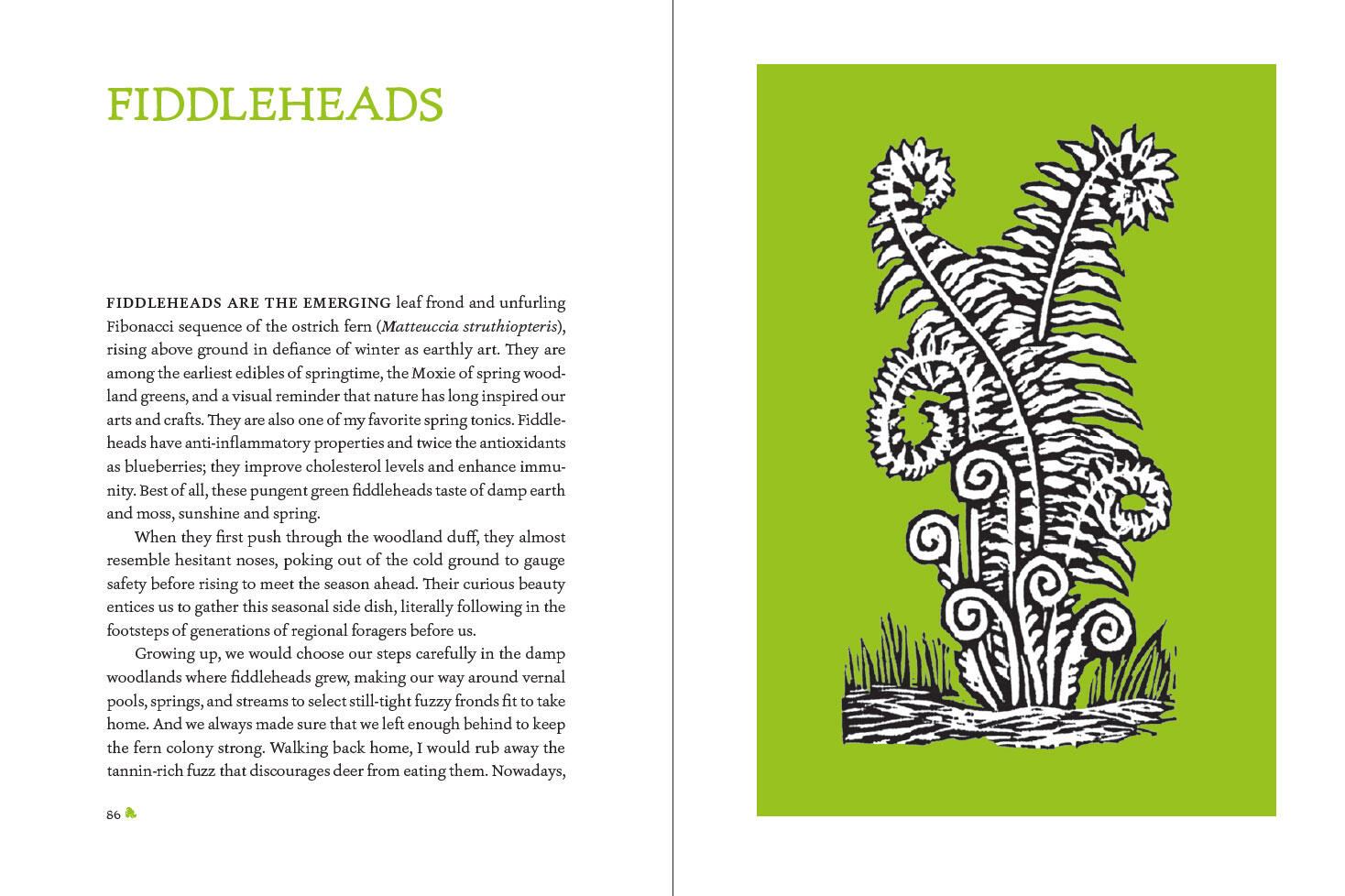

“Forti aims to encourage people to connect with the land and plants, providing inspiration through his experiences and reflections. Forti’s work as a historical gardener informs his approach, which is enhanced by the beautiful wood block print artwork that accompanies each essay and illustrates key ideas throughout the book.” —Booklist

“Social history, botany and home economics merge in a fascinating book to dip in and out of.” —The English Garden

“Interesting information about horticultural practices, skills, and crafts that shouldn’t be lost over time.” —The Washington Gardener

“I know that I will dig into this book again and again to be touched, to be reminded of the many ways we can live lightly on the earth and in community – and eat well.” B>Garden Arts

“Part essay collection, part gardening guide, The Heirloom Gardener encourages readers to embrace heirloom seeds and traditions, serving as a well-needed reminder to slow down and reconnect with nature.” B>Modern Farmer

“A meditation on gardening as an extension of our humanity.”

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use