Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

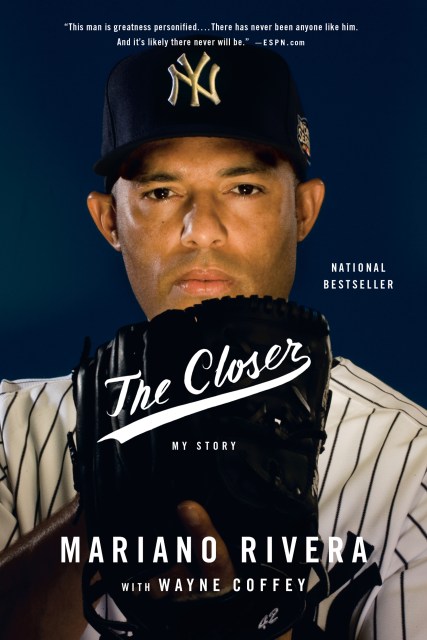

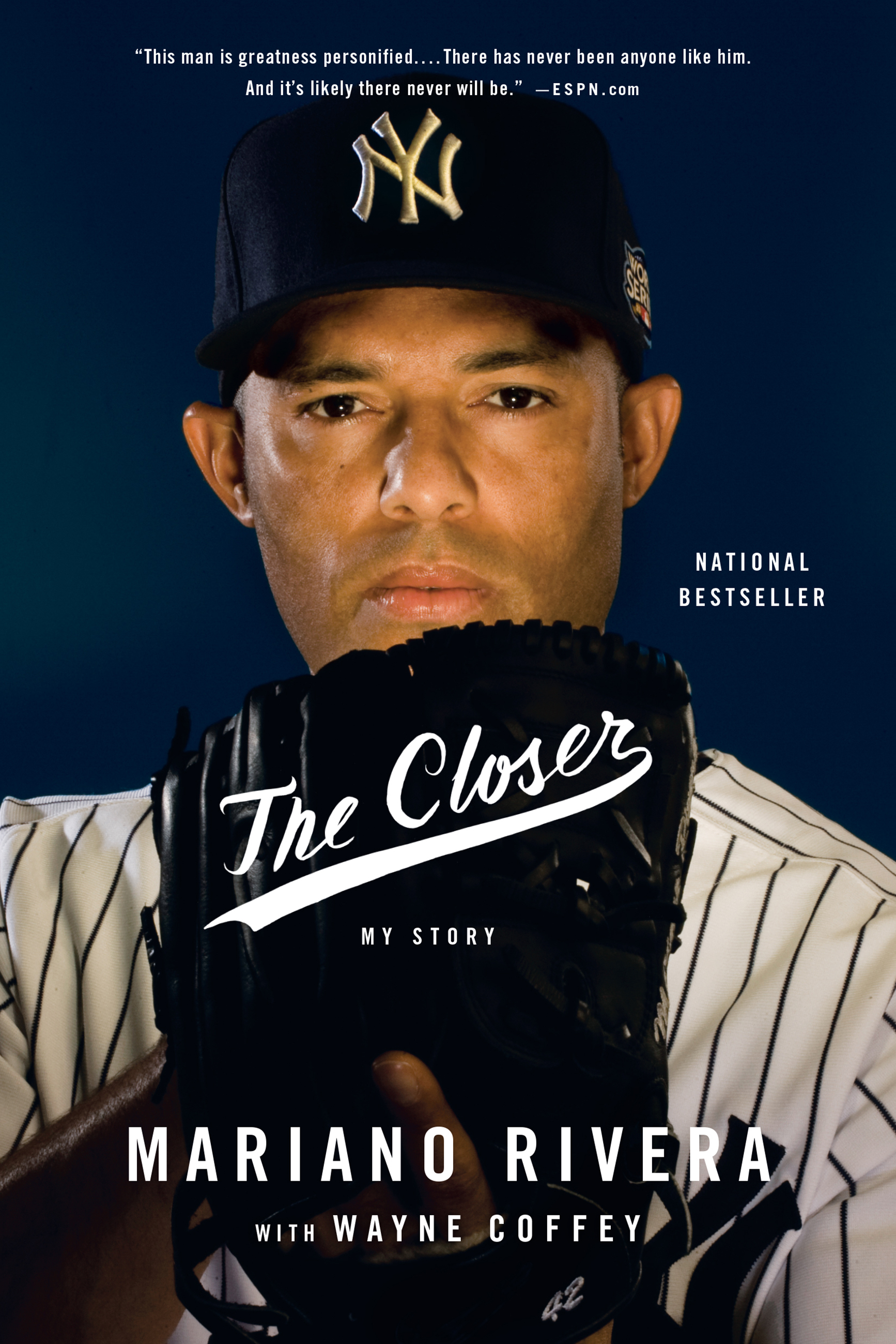

The Closer

Contributors

With Wayne Coffey

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 6, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Mariano Rivera, the man who intimidated thousands of batters merely by opening a bullpen door, began his incredible journey as the son of a poor Panamanian fisherman. When first scouted by the Yankees, he didn’t even own his own glove. He thought he might make a good mechanic. When discovered, he had never flown in an airplane, had never heard of Babe Ruth, spoke no English, and couldn’t imagine Tampa, the city where he was headed to begin a career that would become one of baseball’s most iconic.

What he did know: that he loved his family and his then girlfriend, Clara, that he could trust in the Lord to guide him, and that he could throw a baseball exactly where he wanted to, every time. With astonishing candor, Rivera tells the story of the championships, the bosses (including The Boss), the rivalries, and the struggles of being a Latino baseball player in the United States and of maintaining Christian values in professional athletics.

The thirteen-time All-Star discusses his drive to win; the secrets behind his legendary composure; the story of how he discovered his cut fastball; the untold, pitch-by-pitch account of the ninth inning of Game 7 in the 2001 World Series; and why the lowest moment of his career became one of his greatest blessings. In The Closer, Rivera takes readers into the Yankee clubhouse, where his teammates are his brothers. But he also takes us on that jog from the bullpen to the mound, where the game — or the season — rests squarely on his shoulders.

We come to understand the laserlike focus that is his hallmark, and how his faith and his family kept his feet firmly on the pitching rubber. Many of the tools he used so consistently and gracefully came from what was inside him for a very long time — his deep passion for life; his enduring commitment to Clara, whom he met in kindergarten; and his innate sense for getting out of a jam. When Rivera retired, the whole world watched — and cheered. In The Closer, we come to an even greater appreciation of a legend built from the ground up.

Genre:

- On Sale

- May 6, 2014

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316400756

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use