Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

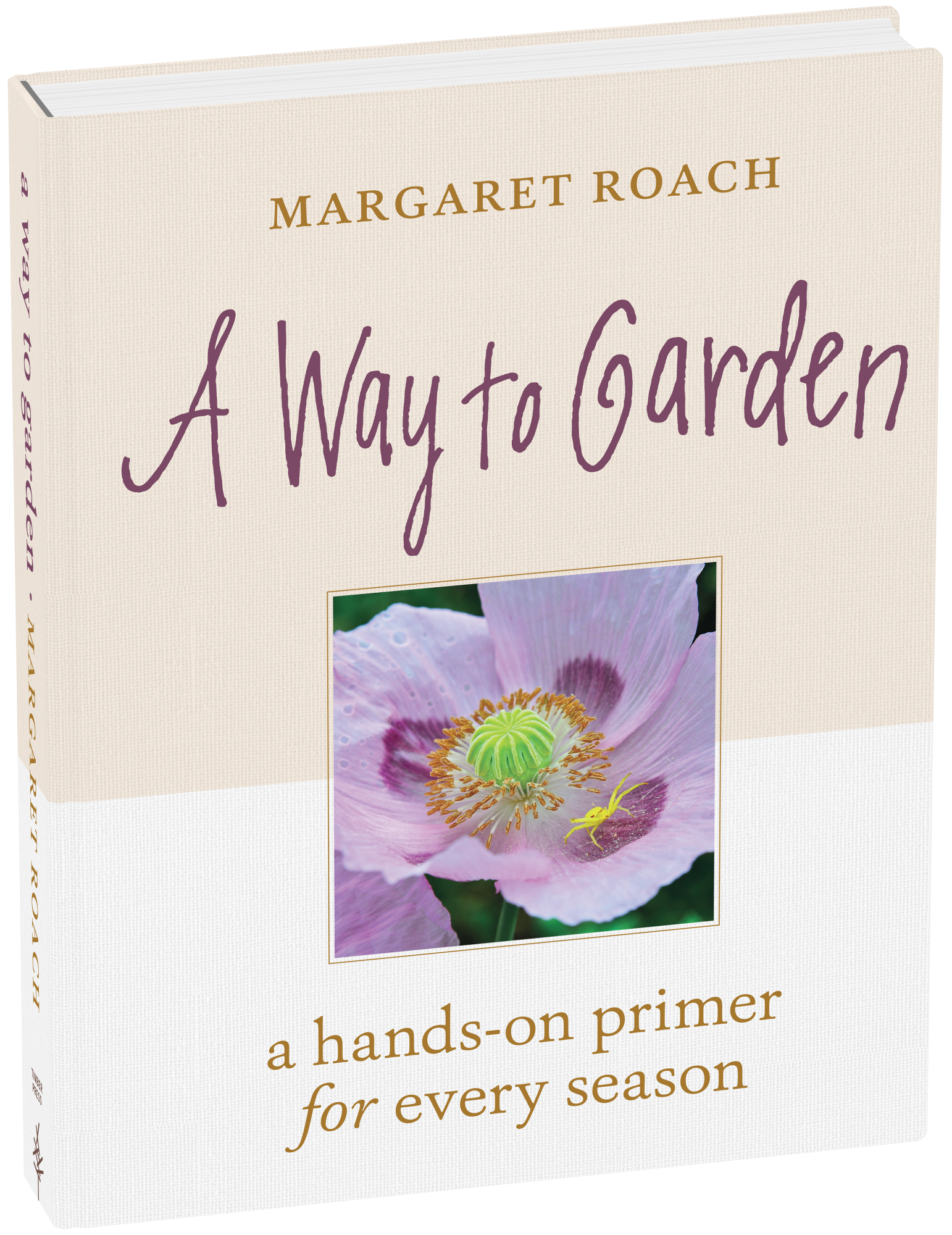

A Way to Garden

A Hands-On Primer for Every Season

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 30, 2019

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Timber Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781604698770

Price

$30.00Price

$38.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $30.00 $38.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 30, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“A Way to Garden prods us toward that ineffable place where we feel we belong; it’s a guide to living both in and out of the garden.” —The New York Times Book Review

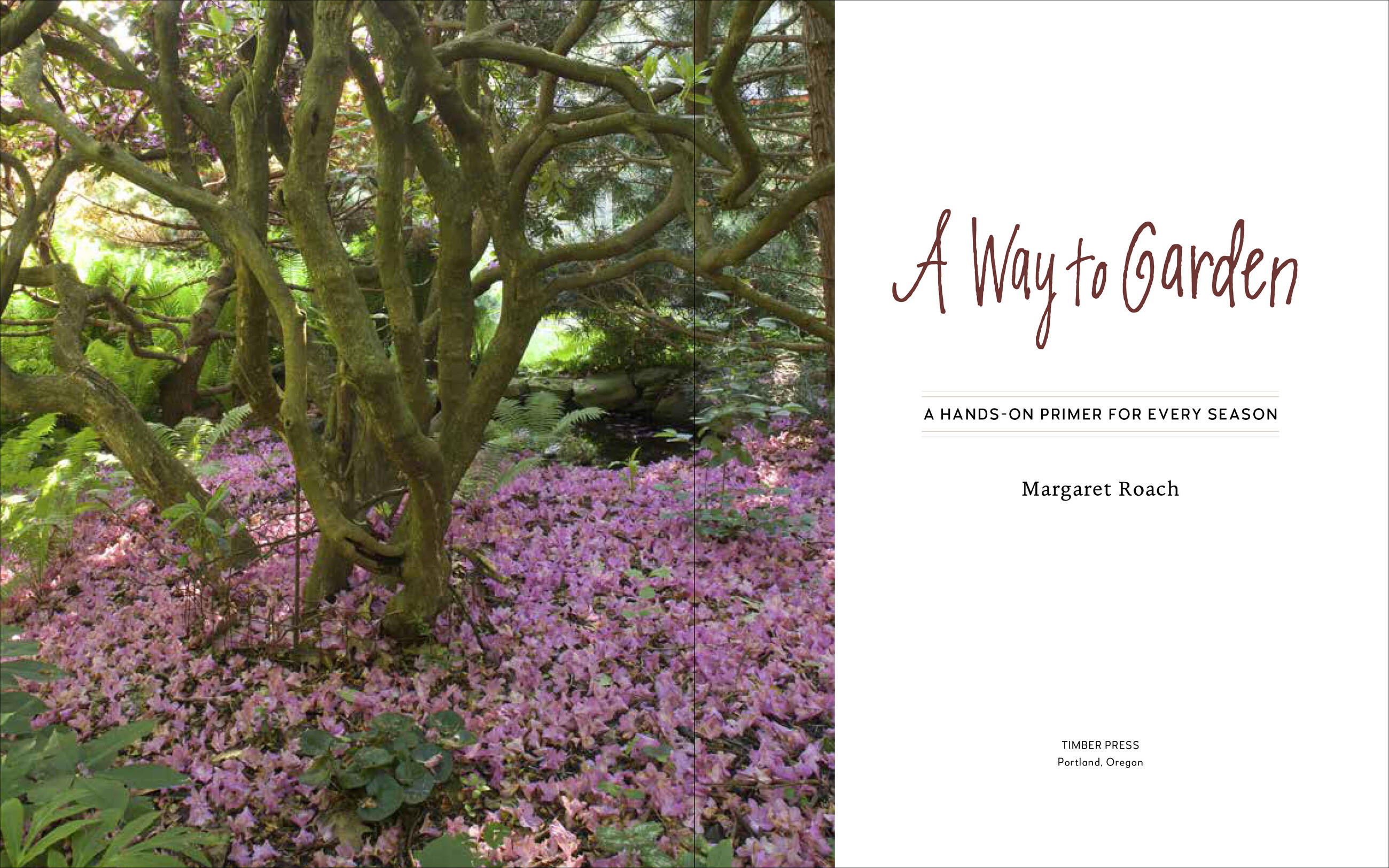

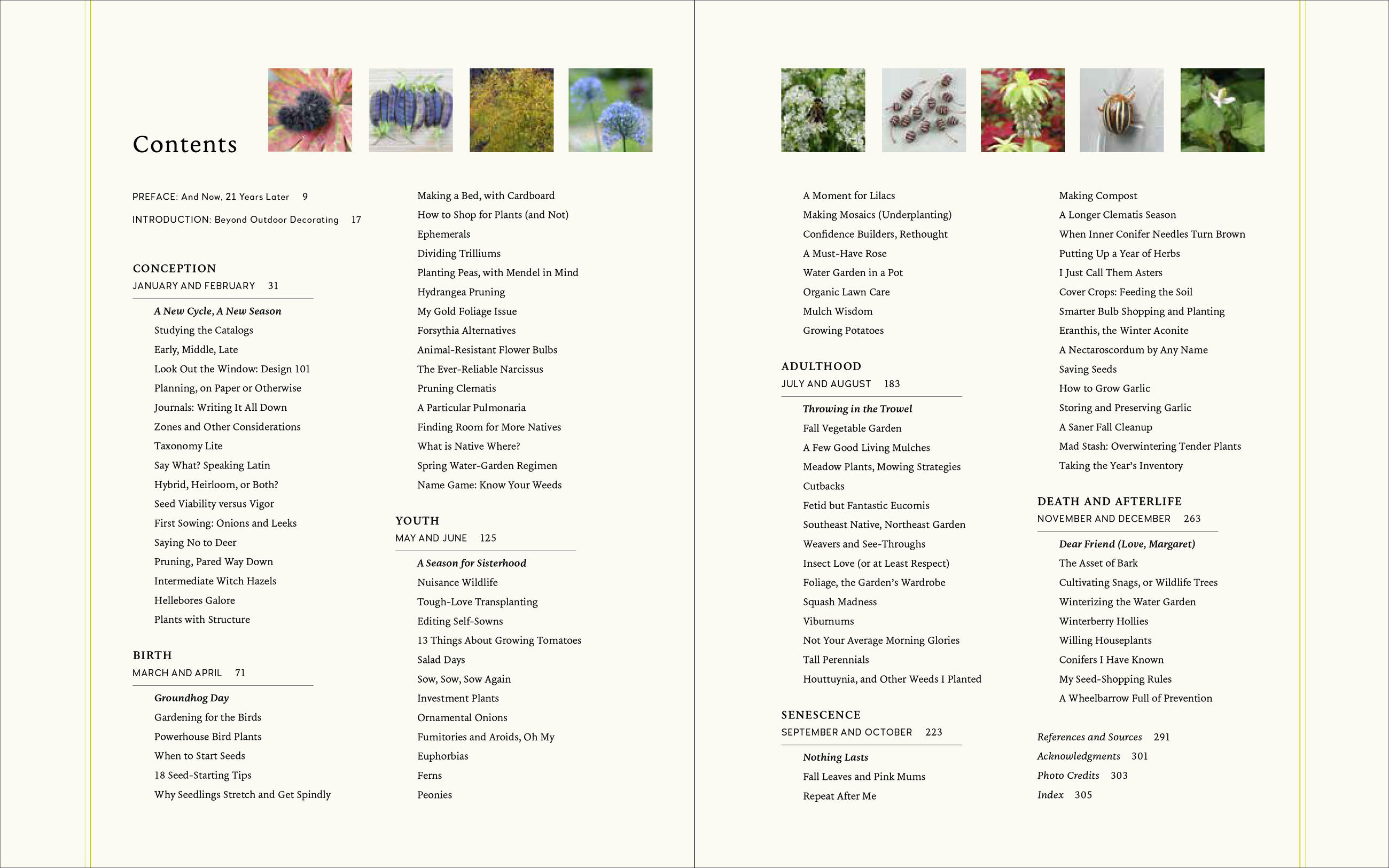

For Margaret Roach, gardening is more than a hobby, it’s a calling. Her unique approach, which she calls “horticultural how-to and woo-woo,” is a blend of vital information you need to memorize and intuitive steps you must simply feel and surrender to. In A Way to Garden, Roach imparts decades of garden wisdom on seasonal gardening, ornamental plants, vegetable gardening, design, gardening for wildlife, organic practices, and much more. She also challenges gardeners to think beyond their garden borders and to consider the ways gardening can enrich the world. Brimming with beautiful photographs of Roach’s own garden, A Way to Garden is practical, inspiring, and a must-have for every passionate gardener.

Genre:

-

“A Way to Garden—sensitive, wise, deliberate, thoughtful and splendidly bossy—prods us toward that ineffable place where we feel we belong; it’s a guide to living both in and out of the garden.” —The New York Times Book ReviewCountry Gardens “Brimming with photographs of her own garden, A Way to Garden is both practical and inspiring for any passionate gardener.” —Michigan Gardener “A lavish book…that invites you into her garden with wisdom on gardening. A Way to Garden approaches each season with a metaphor of terms to relate to the months of the year.” —Empire-Tribune “Roach’s discussion of even the most onerous chore or persistent pest makes me a better gardener; her words inspire me to keep going.” —The Seattle Times “Margaret Roach encourages gardeners to view their yards less as outdoor decorating than as habitat creation, a trend that has gained force alongside greater environmental awareness.” —Boston Globe

"A gorgeous, helpful, and tenderly funny book for anyone who likes putting plants in the ground. I love the fact that it's 'A Way to Garden' not 'THE way to Garden.' Less Hubris, more mulch." —Ann Patchett, author of Commonwealth and State of Wonder

“Roach’s conversational tone showcases her personal experiences while highlighting important horticultural information, making it a compelling book to read straight through that is also useful as a reference for particular details. Readers will appreciate Roach's focus on gardening as a way anyone can help make the world a better place.”B>Booklist

“I love plants and flowers and adore this brilliant gardening guru and her beautifully written new book, just out. It’s useful and gorgeous, a great combination.” B>Kurt Andersen (@KBandersen), host of NPR's Studio 360

“Unquestionably brilliant! I am so impressed with the wisdom of Margaret Roach’s experience and the things she writes about that most garden books ignore.” B>Deborah Madison, author of Vegetable Literacy and The New Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone

“Margaret has an intimate grasp of her subject, along with an appreciation of the microcosm of life within the spaces we garden. Her sparkling wit makes her a joy to read.” B>Fergus Garrett, Head Gardener at Great Dixter House and Gardens

“Her voracious curiosity has kept Margaret on the leading edge. This updated classic distills decades of learning from one of gardening’s keenest minds. It is delightfully free of ideology but brimming with ideas and inspirations.” B>Thomas Rainer, author of Planting in a Post-Wild World; principal of Phyto Studio

"If I could keep just one gardening book, the beautifully written A Way to Garden would be the treasured title. This is Margaret’s finest work to date and why she is my gardening superhero!” B>Joe Lamp’l, Emmy Award–winning creator and host, Growing a Greener World, PBS

“A great book to curl up with . . . Margaret shares insight from her decades of gardening: the ups and downs are laid bare for gardeners to learn, empathize, and find inspiration.” B>Tony Avent, garden writer and founder, Plant Delights Nursery

The perfect reading companion for those of us who feel that gardening is an unstoppable addiction. It will draw you even further in, while confirming what you've always known in your heart: you must have more plants!” B>Jane Perrone, host, “On The Ledge” podcast; former gardening editor, The Guardian

“An indefatigable researcher, Margaret Roach is a whirlwind of enthusiasm for and knowledge of the natural world. This update of A Way to Garden gives us the benefit of so much new information. Thank you, Margaret.” B>Marco Polo Stufano, founding Director of Horticulture, Wave Hill

“Now that I am starting to dig into my own land, I have found a trusted manual to create interest in every season.” B>Joshua McFadden, executive chef and author, Six Seasons: A New Way with Vegetables

“A comprehensive resource and a great book to cuddle up with in the winter while dreaming about your garden plans for the spring.” B>Alexandra Cooks

“Charming, eye-opening and educational. I can’t imagine a better book to curl up with this winter and know I’ll be referring to it throughout each garden year.” I>Susan’s in the Garden

“One of the most fun garden books.”