By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

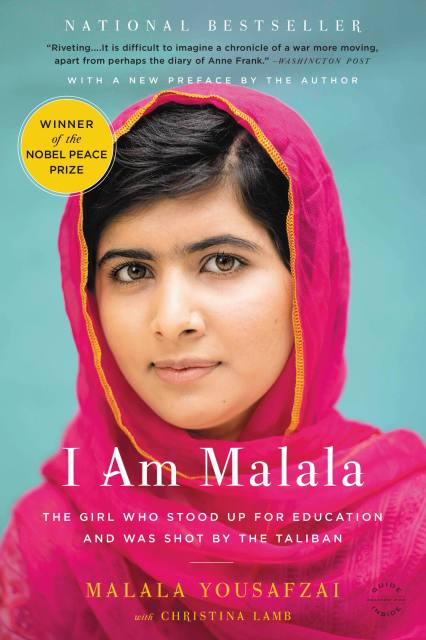

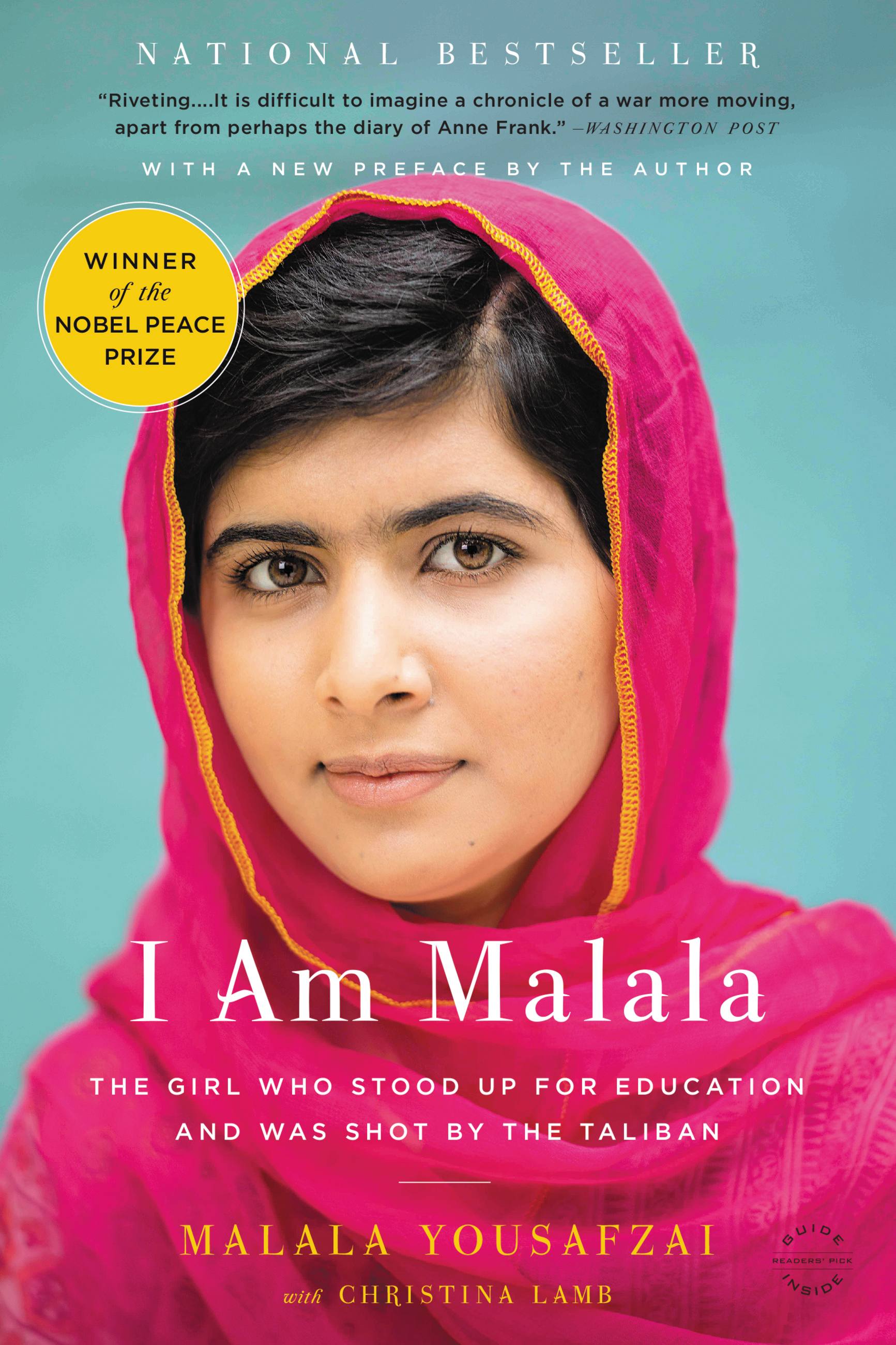

I Am Malala

The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban

Contributors

With Christina Lamb

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 8, 2013

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316322416

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 8, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The bestselling, "remarkable" (Marie Claire) memoir by the youngest recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, I Am Malala will make you believe in the power of one person's voice to inspire change in the world.

"I come from a country that was created at midnight. When I almost died it was just after midday."

When the Taliban took control of the Swat Valley in Pakistan, one girl spoke out. Malala Yousafzai refused to be silenced and fought for her right to an education. On Tuesday, October 9, 2012, when she was fifteen, she almost paid the ultimate price. She was shot in the head at point-blank range while riding the bus home from school, and few expected her to survive.

Instead, Malala's miraculous recovery has taken her on an extraordinary journey from a remote valley in northern Pakistan to the halls of the United Nations in New York. At sixteen, she became a global symbol of peaceful protest and the youngest nominee ever for the Nobel Peace Prize.

I Am Malala is the remarkable tale of a family uprooted by global terrorism, of the fight for girls' education, of a father who, himself a school owner, championed and encouraged his daughter to write and attend school, and of brave parents who have a fierce love for their daughter in a society that prizes sons.

"I come from a country that was created at midnight. When I almost died it was just after midday."

When the Taliban took control of the Swat Valley in Pakistan, one girl spoke out. Malala Yousafzai refused to be silenced and fought for her right to an education. On Tuesday, October 9, 2012, when she was fifteen, she almost paid the ultimate price. She was shot in the head at point-blank range while riding the bus home from school, and few expected her to survive.

Instead, Malala's miraculous recovery has taken her on an extraordinary journey from a remote valley in northern Pakistan to the halls of the United Nations in New York. At sixteen, she became a global symbol of peaceful protest and the youngest nominee ever for the Nobel Peace Prize.

I Am Malala is the remarkable tale of a family uprooted by global terrorism, of the fight for girls' education, of a father who, himself a school owner, championed and encouraged his daughter to write and attend school, and of brave parents who have a fierce love for their daughter in a society that prizes sons.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use