By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

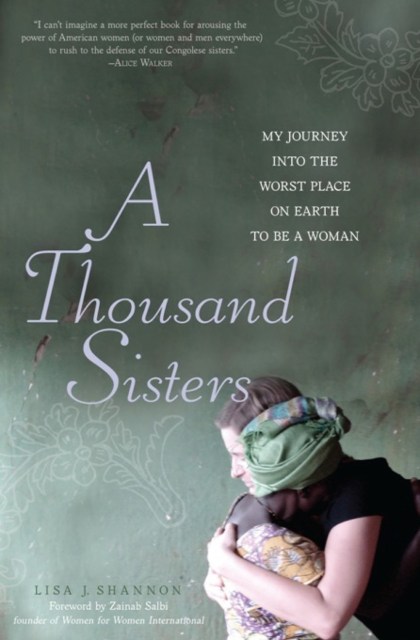

A Thousand Sisters

My Journey into the Worst Place on Earth to Be a Woman

Contributors

Foreword by Zainab Salbi

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 6, 2010

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580053464

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $27.99 $36.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 6, 2010. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Lisa J. Shannon had a good life—a successful business, a fiancé, a home, and security. Then, one day in 2005, an episode of Oprah changed all that. The show focused on women in Congo, the worst place on earth to be a woman. She was awakened to the atrocities there—millions dead, women raped and tortured daily, and children dying in shocking numbers. Shannon felt called to do something. And she did. A Thousand Sisters is her inspiring memoir. She raised money to sponsor Congolese women, beginning with one solo 30-mile run, and then founded a national organization, Run for Congo Women. The book chronicles her journey to the Congo to meet the women her run sponsored, and shares their incredible stories. What begins as grassroots activism forces Shannon to confront herself and her life, and learn lessons of survival, fear, gratitude, and immense love from the women of Africa.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use